One day while I was reading “We Should All Be Birds,” I got a bad headache. I stopped reading, of course. I told my two tweens that they were on their own, and I laid down in bed with the shades drawn and lights off. I couldn’t eat or sleep — I was incapacitated. But I took a painkiller, gave it some time, canceled my plans, and resumed life the next day.

The tiny experience made the book come alive for me. At the time he wrote his book, Missoula author Brian Buckbee had been living with a constant headache for three years. While no one knows the exact cause, he’s been told it’s likely a facet of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS, which also renders him unable to exert his mind or body without paying the price of unbearable pain and severe exhaustion.

What would it be like to be in a constant state of pain? What would happen to the life you’ve built?

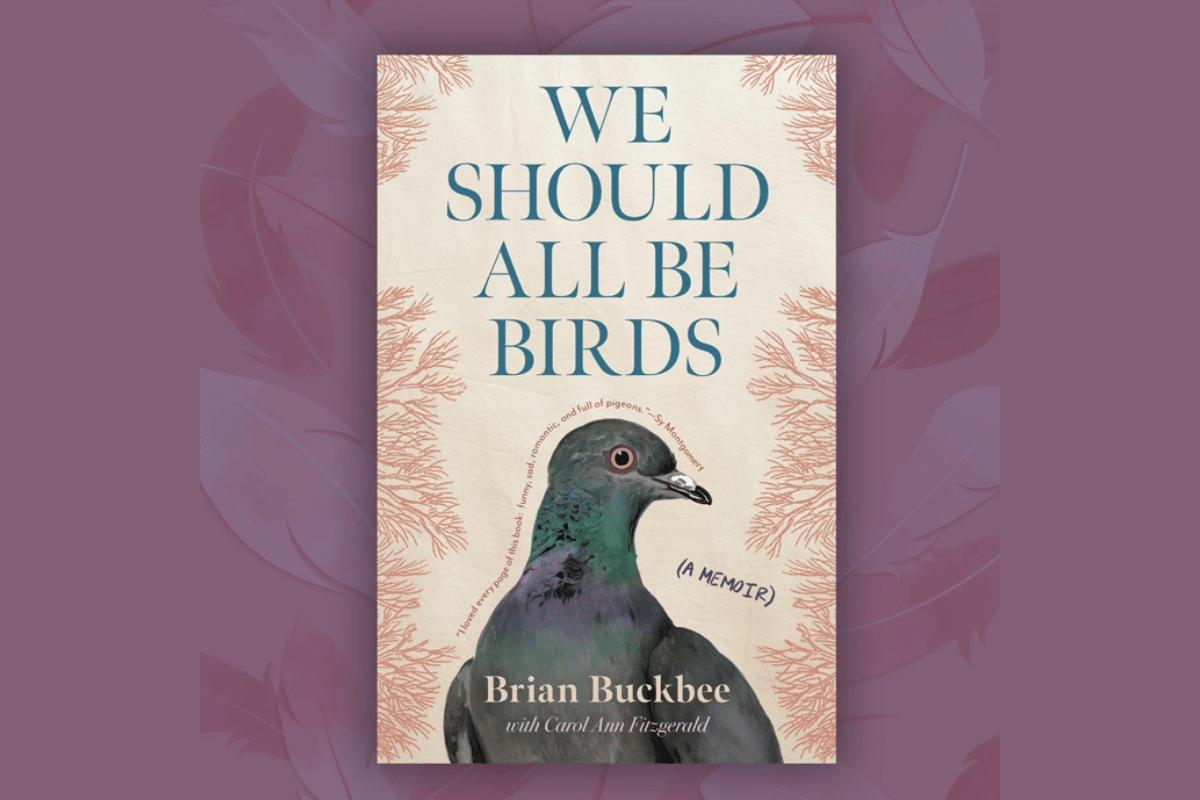

I should pause here and say: This book is supposed to be about birds. Specifically, it’s about Brian’s relationship with Two-Step the pigeon. There has been a glut of books, documentaries, and movies about humans befriending animals. The most recent wave started with the documentary film My Octopus Teacher — which dropped in the darkest part of the pandemic — and has continued steadily in both nonfiction and fiction worlds ever since. And really, this book is being marketed as such — a heartwarming bond between human and bird.

For Buckbee, deep in his illness and deep in the pandemic, rescuing an injured bird that crosses his path changes the trajectory of his life.

For Buckbee, deep in his illness and deep in the pandemic, rescuing an injured bird that crosses his path changes the trajectory of his life. It gives him a reason to keep structure in his day, to love again after being heartbroken and even to spark conversations and stay connected to other humans during a period of severe isolation. (Why is there a pigeon on your head? for example). Over time, his home transforms into part-nest, part-hospital and his yard transforms to a rare safe space for the often-maligned bird species. You know the drill: Who saved whom? It’s a popular and timeless story for a reason.

But to me, the gripping part of the narrative was Buckbee’s experience with chronic illness. As we read, we discover that Buckbee isn’t physically writing at all — he is dictating each sentence into a recorder, one at a time, while lying in bed in pain. Those snippets are then sent to his editor and co-writer, Carol Ann Fitzgerald, who helps him along the path to publication over the course of several years. Reading about their collaboration, it struck me: We probably have so few books about debilitating chronic illness because it’s incredibly difficult to write when you’re living with one. Voices from this huge slice of the population must often be silenced simply because creating is hard enough even without the added challenge. If those barriers to writing end up silencing chronically ill writers, their stories go untold, and awareness about them disappears, too. And that cycle leads to erasure.

The most remarkable part of the book isn’t the birds, though they’re very remarkable. It’s watching the author persist in telling his story (and the story of his birds, who sustain him) while learning about the day-to-day life of someone with severe chronic illness. Following the progression of his condition, his fight to get a diagnosis and treatment, and his search for ways to keep finding joy and hope in the world, made this book a stand-out.

As the book goes on, Two-Step ages past the natural timeline of a pigeon in the wild, and as the reader, you brace for that final act that seems inevitable in books about the bond between human and animal — the “Where The Red Fern Grows” section when the animal dies and the person must find a way forward alone. But in “We Should All Be Birds,” Two-Step remains alive on the final page. And it makes sense. The struggle and grief of the book rests in living, not in dying.

I once heard someone with chronic illness say something like, “People with terminal illnesses have to come to terms with dying. People with chronic illness have to come to terms with living.” To me, this book is the real-time process of the latter. It’s about being in physical and emotional pain without end. It’s about watching something you never asked for take away the things that brought you the most happiness — from relationships to friendship to going for a walk to taking a shower — and then finding new ways to find happiness. And yes, those new ways might involve a pigeon.

Brian Buckbee reads from “We Should All Be Birds” Tue., Aug. 5, from 7:30 PM to 9 PM at a “reading and pigeon gathering” at his house, as part of an off-site event through Fact & Fiction. No dogs. More info here.