Growing up in Frenchtown, Chris La Tray had seen his father pour four decades of life into his work at the Smurfit-Stone pulp mill. As he neared middle-age, and though he’d hoped to avoid the grind, La Tray found himself entrenched in a soul-devouring corporate slog. His health wilted. He plodded along in what seemed like an endless parade of stale sandwiches consumed in hotel conference rooms where particles of joy were siphoned away by climate control systems.

What he really loved was storytelling — reading and writing — and he squeezed it in whenever he could. Mostly he wrote book reviews and music profiles for local newspapers like the Missoulian and the Missoula Independent. He wrote short fiction and sporadically pitched to national magazines. He was in Boston for work when he spotted his writing in a national periodical for the first time — a story about Behring Made knives in Blade Magazine. It was a rare moment of affirmation in an early freelance hustle spotted with inconsistent rewards. And it didn’t feel like enough.

When his father died in 2014, La Tray felt an urgency to correct his course. He began to plot a way to wriggle free from his demoralizing tether to middle management.

La Tray planned to go broke.

He hung a whiteboard near his front door and outlined his steps toward liberation. Under the title “Freedom 17,” in dry erase marker, he scrawled a list of tasks to accomplish before leaving his job:

He’d use the last of his corporate money to pay off debt.

He’d make repairs on the house.

He would tackle neglected life projects that he didn’t want hanging over his head once his stable income was dried up.

He gave himself two years to stage his exit and re-engage with humanity. Spirited by a deep curiosity about poetry, the generative world-making of the J.R.R. Tolkien books of his childhood, and the subsurface rumble of Big Human Questions, La Tray set out on a quest to systematically transform his life into that of a Writer.

In April 2015, though, after a minor disagreement with work colleagues — a full year ahead of schedule, his whiteboard far from clear — he got irritated. “Fuck it,” he told his managers. “I’m gonna leave at the end of the year. Replace me.”

And that’s what he did.

Despite believing his writing was going to set the world ablaze once he was free, Jan. 1, 2016, marked the start of a dark, six-month period of languishing, during which he didn’t write much at all.

“Once you finally leave and you’re in a place of alleged relaxation, you realize the physical and mental trauma that’s built up has had an actual impact on your sense of personal morality,” La Tray told me. “Nobody was calling me for anything. My identity had been tied up in my work, even if I hated it, and now I was just home. Recovery took a long time.”

As he emerged from that haze of recuperation, he took on book-related writing projects and a part-time gig at the downtown bookstore Fact & Fiction. In 2017, La Tray went to the Beargrass Writing Retreat as a bookseller for the shop. He passed those precious retreat days sitting behind a folding table piled high with other authors’ books.

“I was looking at all these other people there, thinking, None of these fuckers are doing anything I can’t do. I decided I’d never go [to Beargrass] again as an invisible bookseller. I wanted to be one of the people who has something to say.”

And La Tray has made good on that resolution. He’s got two books of mostly poetry — including “One-Sentence Journal,” which won the 2018 Montana Book Award and squarely established La Tray in the regional literary scene — and his new, much-anticipated memoir, “Becoming Little Shell.” His Substack newsletter, An Irritable Métis, has amassed over 13,000 Irritable Readers since late 2019. He gives cultural workshops and interviews and participates in as many literary things as time will allow for. He teaches poetry to reservation kids. He’s an ambassador for the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, and nearing the end of his two-year term as Montana’s poet laureate. Last month, the University of Montana’s Environmental Studies program announced he’ll be the 2025 Kittredge Distinguished Visiting Writer. To show up for it all, La Tray drives around a lot, traversing the state and the country like a pollinator of all things story-related.

“Over the past 10 years I’ve gone all in,” he says. “I’m out actively doing the things I need to be doing, and things arise. And they really have for me. You can call it a weird, white-lighty manifestation, but it’s really just the universe participating in the decisions I was making. The more you open up to Kitchi Manitou, to the Great Mystery, the more it acts for you.”

“The more you open up to Kitchi Manitou, to the Great Mystery, the more it acts for you.”

The mystery, however, involved more than alchemizing a creative life outside the corporate framework. In order to be the writer he wanted to be, La Tray needed to know where he came from. About the Chippewa side of his family that his father didn’t — or maybe couldn’t — talk about.

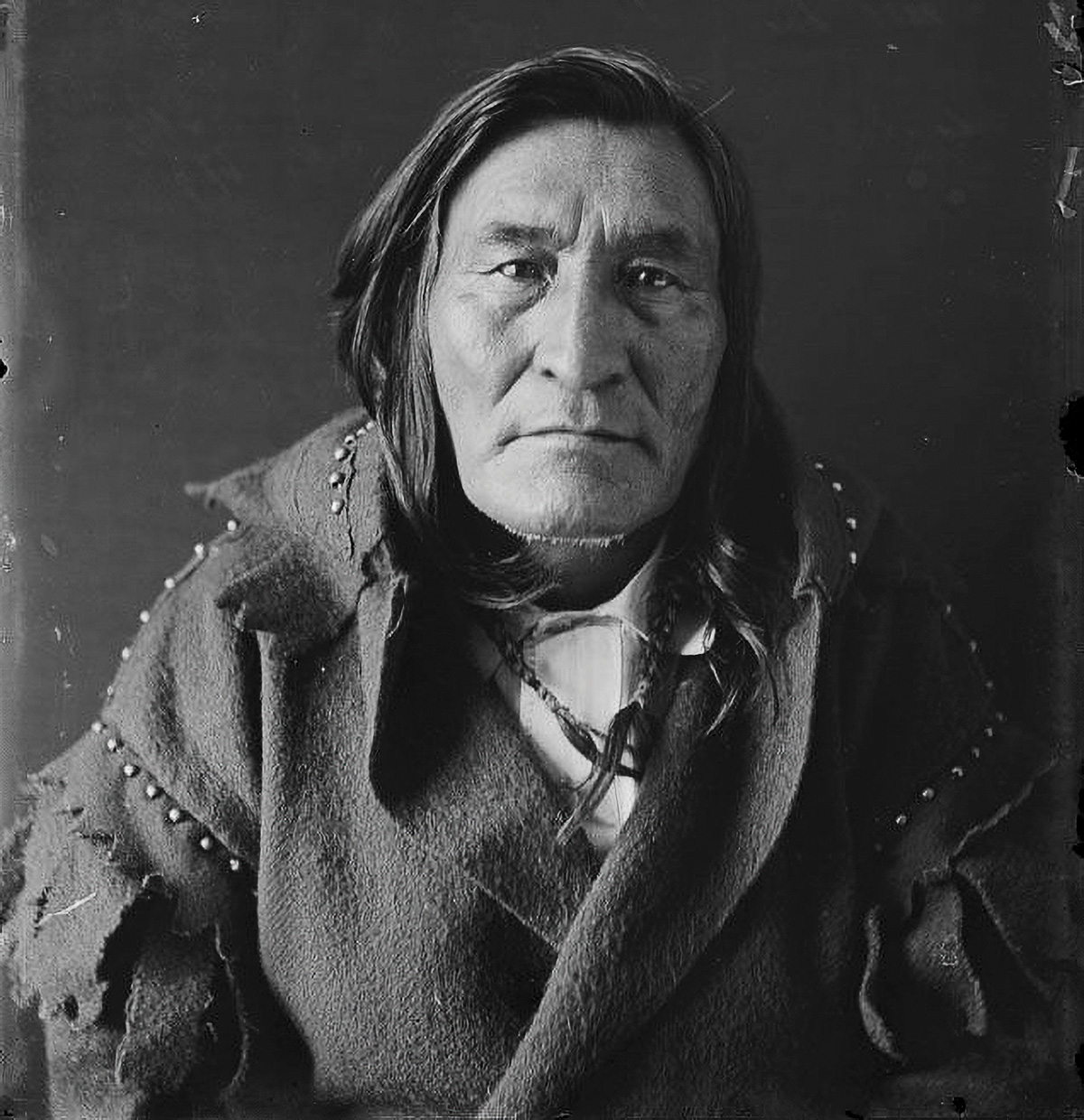

The more he learned, the deeper in he got. Through conversations and research he excavated both beautiful and sordid narratives in complex layers. Reciprocal relationships with land. Fouled treaties. Buffalo jumps. Boarding schools. Meaning-making myths, vanishing languages, honored ways of knowing. As these stories became his own, so did a binding responsibility to expose and venerate the truth.

The end game wasn’t necessarily what he’d thought it was. He couldn’t silo himself as a writer behind a desk. La Tray, overwhelmed as he sometimes is by a generalized, perhaps misanthropic disappointment in other humans, has consistently made the choice to be a public person. It’s a connective, community-dependent, prosocial thing to do, even though writing itself is a lonely act. Even though he may be angry with the world, La Tray knows a connected world is a good world.

Writing has become a tender mechanism, an ancient mode of doing and connecting in the world — also of discovering, dismantling, deconstructing, and demystifying. La Tray makes choices in service of his emerging mission: to heal fractured relationships through story, and to debunk the insidious lies baked into American history.

By his own admission, La Tray has become radicalized: He will never again waver in his work to repair what is horribly broken.

A few years back, after a decade of teaching high school, guiding seasonally, and writing stories that were mostly about rivers, I committed myself to running an arts-based outdoor education organization. It’s called Freeflow Institute, and I named it for the free-flowing rivers that connect mountains to oceans, and for the streams of ideas that, unobstructed, coalesce into meaning, into stories. La Tray has been an instructor at Freeflow since 2019, and we’ve spent a lot of time together on rivers, in storms, and in hard conversation with aspiring storytellers.

On an irritatingly warm January morning in 2024, I met La Tray at a coffee shop to plan the workshop he’d teach with Freeflow in June. Casually and between sips of my Americano, I confessed that I was trying to prioritize writing for myself, trying to toil less with spreadsheets and invoices and to spend more quality time with the arts.

“The arts matter, Chandra,” La Tray told me, sitting tall across the coffee shop table like a mountain. “You have to fight against your capitalist socialization.” I nodded. But in silent retort: How do you make a living in this country without a pint or two of capitalist blood streaming through your veins?

La Tray told me he’d been digesting the Arnold Schwarzenegger book “Be Useful,” which asserts that there is no use in kind of doing something. Instead, you’ve got to commit completely, as though you’re running a rapid in a river.

Commitment is inked onto La Tray’s body. Tattoos on his arms and hands — ”the original Palm Pilot,” he jokes — serve as permanent reminders.

Commitment is inked onto La Tray’s body. Tattoos on his arms and hands — ”the original Palm Pilot,” he jokes — serve as permanent reminders.

On his forearm, he has a tattoo of the “Men Wanted” ad that Ernest Shackleton supposedly posted in a London newspaper ahead of the 1914 Endurance expedition — art he had done locally with a gift certificate his mom gave him for Christmas in 2015. Shackleton’s “hazardous journey” promised “small wages, bitter cold, [and] long months of complete darkness.” Which basically describes the work of a writer. Or the work of someone trying to address the transgressions of an entire nation.

The number 574 tattooed across his knuckles is a reminder of his people, the Little Shell tribe of Chippewa Indians, who, in 2019, became the 574th tribe to earn recognition from the federal government. It was a hard-won battle, 150 years in the making, the story of which he braids into his own narrative of identity and individuation in “Becoming Little Shell.”

La Tray told me about the next tattoo he planned to get. He had decided to decorate his other forearm with the Seven Grandfathers: seven North American animals that animate seven Anishinaabe principles for living. He’d come to rely on these animals as guides as he navigated the surly waters of book-writing and truth-telling. The Grandfathers — Eagle, Turtle, Raven, Beaver, Bear, Wolf, and Buffalo — would wrap around his forearm, living there together, just as naturally as they do in the Yellowstone ecosystem.

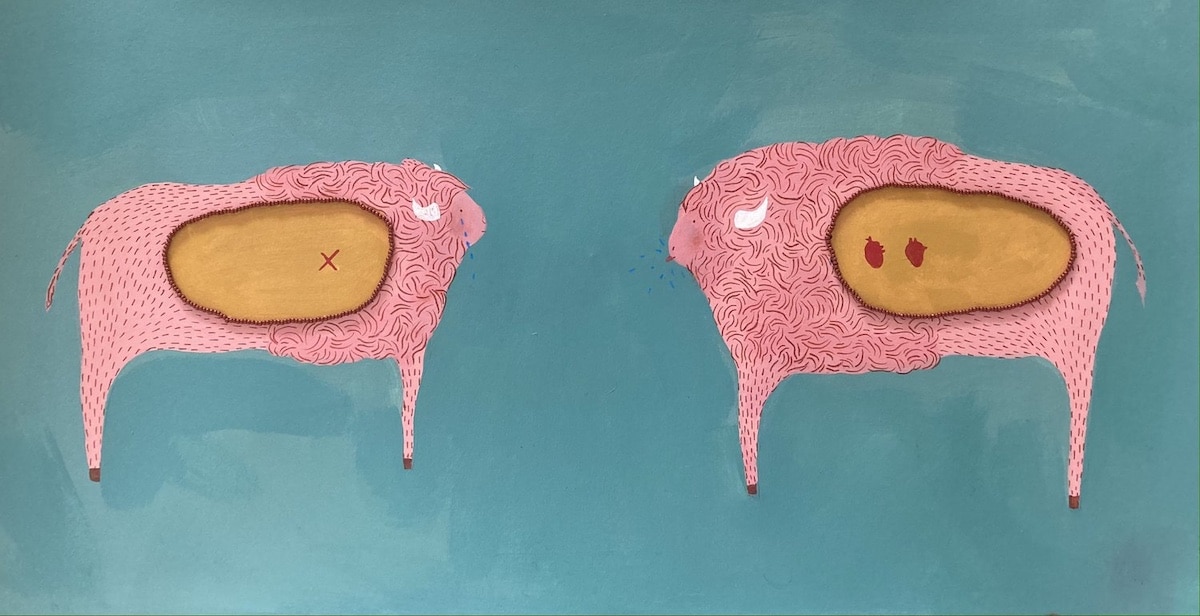

A while back, I gave La Tray a painting of two pink buffalo by the young Crow artist Stella Nall. It’s called “Stolen Heart.” In the Seven Grandfathers teachings, Buffalo, or Manaaji’idiwin, who represents respect, reminds us to go easy on each other. I didn’t know this when I chose the painting for La Tray. But I did know that La Tray loves buffalo. And I liked that one buffalo was missing its heart, and the other had two hearts, and the two-hearted buffalo was, playfully, sticking its tongue out at the no-hearted one. I felt a levity, a sweetness, in the image. I also, somehow, saw La Tray and me in those two buffalo. And it felt like friendship.

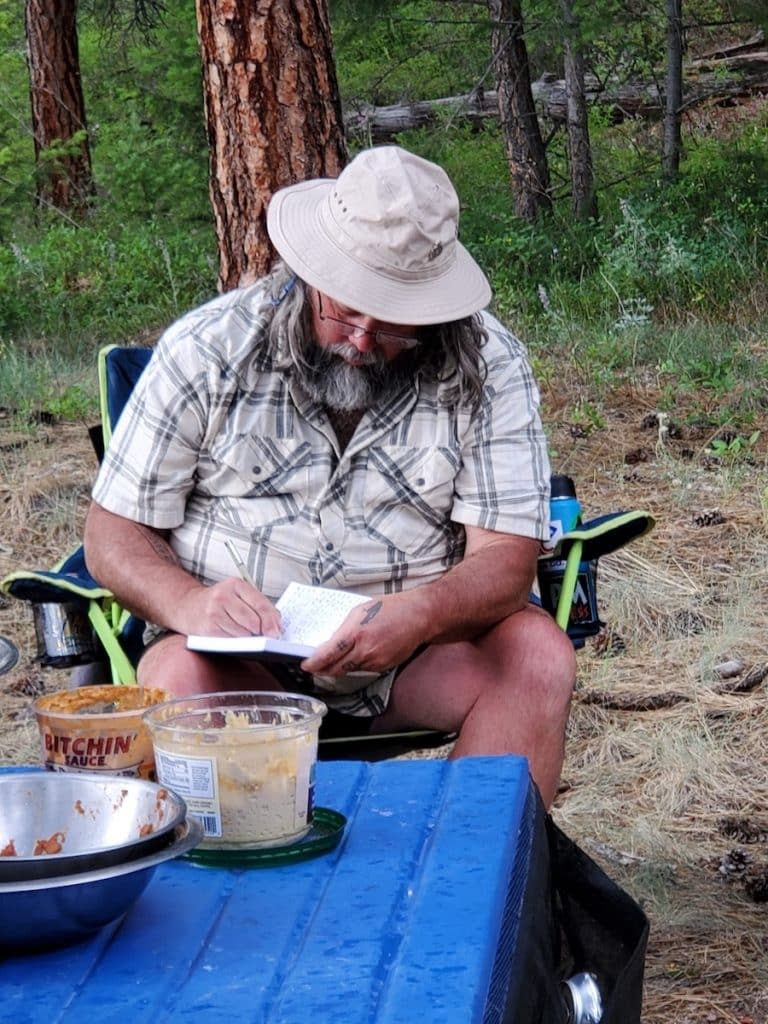

It’s June 2024 and we’re camped at the put-in for Idaho’s Main Salmon River, where La Tray is leading his fifth writing workshop with Freeflow Institute. Over our wintertime coffees and smoothies, La Tray and I plotted the format and purpose of the field course. We’d float 89 miles of free-flowing Salmon River, snaking between canyon walls and the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. The journey would last six days. Each morning, we would drink coffee and eat eggs, and after a morning workshop session (discussion, writing, reading, grappling with tough questions), we’d pack up camp and head downstream in rafts and inflatable kayaks. Each night we’d camp at a new spot. Each day, from the boats, we’d see bighorn sheep and bald eagles. Life on the river is very good.

Ahead of our now-annual river trip together, I buy La Tray sunscreen, forgetting each year that his “pelt is his sunscreen.” He doesn’t sleep in a tent. He wears the same shirt each day of the trip. La Tray maintains admirably close proximity to elemental discomfort.

Each Freeflow Institute workshop has a theme. La Tray titled this year’s workshop, “The Good Life,” and it was not billed as a craft workshop. (La Tray maintains he “doesn’t have an academic bone” in his body, and he’s not interested in teaching academic modes and methods of writing.) Instead he aims to teach these 13 participants, women from all across the country, new ways of looking at the world through the lens of his guiding theme, the Anishinaabe concept of Mino-bimaadiziwin, or The Good Life. In his invitation to the workshop, La Tray wrote, “To be in balance, at peace, and in good health, means that we must be in such a state not just with ourselves, but with everyone around us. Is this even possible?”

“To be in balance, at peace, and in good health, means that we must be in such a state not just with ourselves, but with everyone around us. Is this even possible?”

This year’s Freeflow course is not just a workshop. It feels like a confluence: La Tray is the poet laureate. “Becoming Little Shell” was about to come out in August. His voice carried farther and his platform was bigger. As he was learning more about the history and connecting with more people, the stakes were growing ever-higher.

Often, on river-based field courses like this one (which are necessarily expensive and require a significant commitment of resources and time away from work) there’s only one Indigenous person on the water with us. And often, La Tray, as the instructor, is that one Indigenous person.

“I want more of us back on the water, to be transformed by the river, and the landscapes, and the deep interactions with other committed and creative and thoughtful people, and then go back out into the world motivated to make changes in it. Just as I have been,” he wrote in his March 17, 2024, newsletter. “The world is the original storyteller and our original teacher, and too many of us have forgotten how to pay attention. I want more people to have a chance to listen again.”

Four of the participants in our circle now are Indigenous. They are here because of a scholarship campaign La Tray set up a couple months prior via his Substack and in collaboration with Chickadee Community Services. Over six weeks in March and April, La Tray did what he could to grow the fund: He matched scholarship contributions from his readers; donated 50 percent of all new paid Substack subscriptions; and donated $10 for every preorder of “Becoming Little Shell” via Fact & Fiction. There were no strings attached, no questions asked. After collecting names of interested people by email, he’d pulled four winners’ names out of a hat.

“Native folks, and other marginalized communities, lack opportunity. This is an opportunity to participate in something meaningful. But it’s not much of an opportunity if one is the only Native invited to such an event. Then it feels like a token, or a box check, and it’s uncomfortable,” he wrote. “I want to facilitate getting people out to hear [rivers] whisper us back to a better relationship with Everything.”

Our first night together, at the Corn Creek campground, where all Main Salmon River trips begin, we gather in a circle for introductions and a discussion of why we are all here, within the context of the workshop’s “Good Life” theme.

L., a grandmother from the Blackfeet Reservation, is worried about needing to pee in the middle of the night. But, also, L. says her shoulder pain miraculously abated right before this trip. She needed to be here. The universe arranged this.

J., a Nimiipuu linguist and professor, says Nimiipuu language, spoken aloud, awakens the land. J. wears shell earrings. She says the shells crave the water.

H., a pHD candidate in Boise, sees La Tray’s questions around change-making mimicked in the ecological concept of legacy effect, which asks: What will be left of your actions in 10 years? How will your choices show up in the world later?

La Tray riffs off of H.’s introduction of legacy and weaves it back into discussion of storytelling. “The words you share or don’t share create your legacy.” Commitment to some truth initiates a ripple effect. You’ve got to commit to something. He adds, “Don’t worry so much about what you want to write; write instead what needs to come out of you.” As writers, our work is to be conduits for truth.

“Don’t worry so much about what you want to write; write instead what needs to come out of you.”

The skin on La Tray’s forearm is peeling. His Seven Grandfathers are still inky fresh and vulnerable to the sun. But he keeps his sleeves rolled up, tattoos exposed, as he prepares to share the Seven Grandfathers teachings over the coming days.

Part of La Tray’s mission is to get people to love their backyards. If you can live in a place, you can love it, too. If you can truly love the little plot of wetland, he says, behind the convenience store on your block, then loving a place — an entity — like the Salmon River is a given. Relationships — not laws or regulations — are the key. The land craves us, he says. It wants us to be in relationship. Everyone, everything, around us craves our attention and love.

Another piece of the mission — and why he teaches — is to encourage people to tell their stories. “When I talk to Indigenous kids, I tell them they have to do some form of art to tell their own stories,” he told me. Otherwise, when some other writer parachutes in to report your story, they’re going to get it wrong, no matter how compelling or compassionate their interpretation may be. “I am grateful for the opportunity to tell my story and my people’s story because it’s one I’m still living. I didn’t move on to something else. This is it: This is what my life has been, is now, and will be moving forward. And I encourage others to do that same thing with their own lives.”

In the light of a lingering solstice sun, the young, smart trip leader gives her welcome talk, orienting us to the river and to the logistics of rafting through wilderness. She folds her hands in her lap and begins to talk about “big W” wilderness designation and the legacy of protection. She knows this topic is fraught, and she chooses her words carefully. She describes the 1964 Wilderness Act; that it was named to honor U.S. Senator Frank Church; what wilderness protection does for a place. It allows us as river travelers to experience a relatively “pristine” corridor. But, she says, it comes with problems, too. She goes on, but she notices La Tray has been shifting — squirming, really — in his folding camp chair.

La Tray interjects. The river guide’s eyes are wide like a doe’s but she listens. La Tray booms: His people, and the relatives of the four Indigenous women in our circle, were violently and systematically removed from this place in the name of preservation. For the enjoyment of certain people. Of settlers. For the enjoyment of the white people in this group.

Language is everything, he continues. English is built for commerce, not for relationship. For all its flaws, English is the primary language to which La Tray has access and with which, for now, he makes his living. He is committed to the complication of using the English language to reveal truths about itself and about the people who speak it. The words we use to talk about something as problematic as wilderness, La Tray explains, matter deeply. The words in the young river guide’s orientation talk, he says, are inadequate, too soft. He has consistently admonished organizations and individuals for their practice of giving land acknowledgements — worthless, performative checkboxes that La Tray calls “the progressive liberals’ version of ‘thoughts and prayers.’”

Through gritted teeth and fever-pitch frustration, a slight tremor in his voice, La Tray offers his solution: to act with love. “We have to enter stuffy rooms and hard conversations and relationships the same way every time — with love.”

There’s something confusing and eternally motivating about a great teacher who is, at baseline, grumpy, hard to please. It’s not an easy relationship. It requires a bit of cortisol-lubricated vigilance. You don’t want to disappoint. You want to show them you’ve done the reading and that you get it. You want to be better, and so you try harder.

With his newsletter, La Tray has created a community of learners who crave this sort of teaching. Real, challenging, and sometimes painful. The reward for sticking with it, with him, is that you’re in on his jokes. And you get to share in his celebrations when they happen, too.

The morning of Aug. 20, 2024, publication day for “Becoming Little Shell,” La Tray sent a newsletter to his cadre of Irritable Readers: “I’m overjoyed that people who read it will come away knowing a little more about the Little Shell and the Métis. But it also feels a little like going to the pool shirtless and wearing trunks a size or two too small: pretty exposed.”

That’s how he’s chosen to live this Writer’s Life. Exposed and edgy, like any real rock star. Except he can’t just walk off the stage. He’s not just performing. And this isn’t a single act that ends with a mic drop and a post-show high-five.

That’s how he’s chosen to live this Writer’s Life. Exposed and edgy, like any real rock star. Except he can’t just walk off the stage. He’s not just performing. And this isn’t a single act that ends with a mic drop and a post-show high-five.

Writing a book is a long game. As is publishing. As is affecting systematic changes within a culture.

La Tray’s commitment to process is paralleled by the Little Shell Tribe’s pursuit of federal restoration.

“Common culture has an idea that things should happen fast,” he told me. “You have an idea on Thursday and expect it to be implemented by Friday afternoon. I use the Little Shell as an example of how the long game works: 150 years toward recognition and restoration. We could have given up along the way, but we didn’t.”

Back on Dec. 20, 2019, La Tray wrote the very first Irritable Métis newsletter, the content of which now forms the backbone for the final chapter in “Becoming Little Shell.”

That evening, then-President Trump had signed the National Defense Authorization Act, tucked into which was Sen. Daines and Sen. Tester’s Little Shell Restoration Act. The irony was glaring:

With the flourish of one leader’s pen, it became the imperative of the Little Shell, as a suddenly sovereign nation embedded within a nation of occupiers, to watch and to act. “But we are a sovereign nation who are now in a position to deal in strength with another nation who surrounds us on all sides. A nation we must never forget rarely has our best interests in mind. We must be vigilant, and we must be wary,” he wrote.

La Tray’s Little Shell were repeatedly displaced. They were denied a reservation, and therefore denied home. They were denied tribal recognition, and therefore denied belonging. The peripatetic Métis lost their freedom to wander when white settlements rooted across the landscape.

La Tray lines out the undeniable link between historical landlessness and present day houselessness. “When I see these people, no less beautiful in their humanity than anyone else, I see echoes of mine, the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, during those unfortunate years as landless Indians.” He asks, “How is what we are doing in America now to others any different than what has been done to us as Chippewa-Cree/Métis people?”

For the Little Shell, federal restoration was not the end. There’s still work to be done.

For La Tray, Good Ancestor is an identity determined by the things we do when we’re alone, when no one but the ancestors are watching. It’s defined by the little choices we make, which all add up to the legacy we’ll leave behind.

“When we don’t make progress on the big picture, long-term stuff, it’s due to lack of commitment,” he told me. “Commitment is built into the Anishinaabe language. Relationship is built into words for both ancestors and descendents; we have the same word for great-grandparents as we do for great-grandchildren. There’s an evolving recognition of who these people are to you, your responsibility to them, and our decision-making is built into our worldview.”

In working to make change, you’re going to come up against resistance. I often wish to be like water, flowing smoothly between the rocks, sliding right past the resistance. Sometimes, though, water needs to make big waves, hydraulics that upend our reality, send us deep, and reshape us. We need to be that water, too. We need to be both. And ultimately, like water, we’re all going to the same place. We all crave the same things.

Sometimes, though, water needs to make big waves, hydraulics that upend our reality, send us deep, and reshape us.

It’s August 21, 2024, and the Copper Room at the Missoula Public Library is buzzing. Tonight there are things to celebrate. The day before, the final Freeflow field course of the year got off the river; our season ended without incident. Also, “Becoming Little Shell” was released amid much fanfare. We are here for La Tray’s official book launch.

Four flags hang behind the lectern. From left to right: the Métis flag, Little Shell, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, and in white letters, Landback emblazoned on a red background. An honor song opens the program. And as La Tray is introduced, “Black Shuck” by The Darkness plays over the PA. Black Shuck, that folkloric canine embodiment of identity, fear, guardianship, and contradiction: “My walk-up song!” He laughs and strums an air guitar.

He opens a conversation with a public audience the same way each time: “Boozhoo, Indinawemaaganidog. Hello, all my relatives.” And then, this time, he breaks down.

The tears slow and he says, smiling, “Wow. This is not how I planned it.” But anyone who has been listening to and learning from La Tray over the past decade knows he chokes up often. His heart is perpetually exposed.

He asks the Little Shell people in the audience to stand. “This book is for you. Never forget…” A dramatic pause. He gathers himself and steadies his voice. “…that you are the descendents of the mightiest buffalo people the world has ever known. Come at me, Blackfeet!”

The audience laughs. We’re in on the joke and it feels good.

Then La Tray surprises us. He’s just come from the Wilma Theater, a couple of blocks away, where he was asked to speak at a fundraiser for the Jon Tester campaign. He says, to the shock of those of us familiar with his ideologies, that he volunteered to give the land acknowledgment for Tester. He admits hesitantly that the performative nature of land acknowledgements seems to slowly be giving way to something more meaningful within the culture. And with that, his own “glacial relationship” to the practice is “starting to budge.” Even La Tray’s opinions — galvanized and monolithic as they seem — are mutable. We are all subject to change.

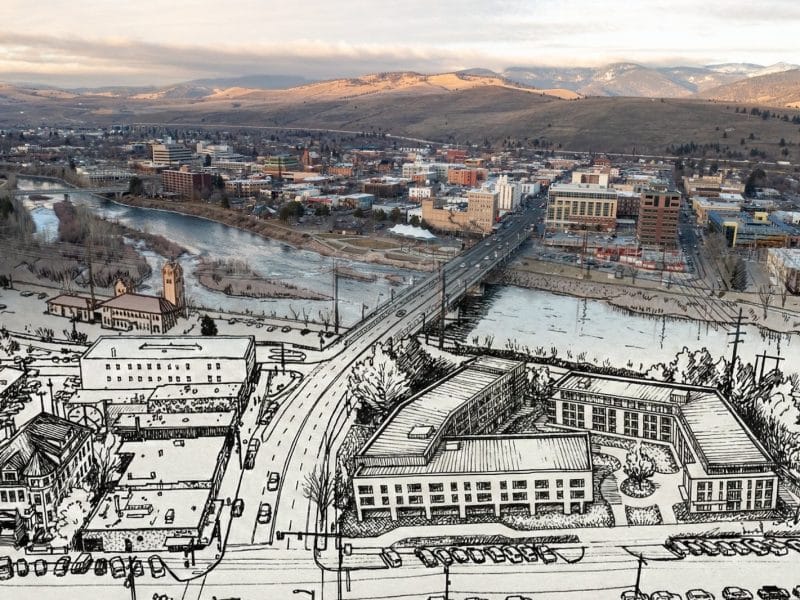

And so, in his own way, in front of that theater full of “big shots,” La Tray had summoned an image of a Missoula valley underwater. And then the flood. The land here, once drained and dried, hosted communities of creatures that had to get along, to share space. Eventually humans moved in and across and through this place. They did as humans do. And now, in this current age, we just can’t seem to get along. He acknowledged the living relationship between us all, including the ancestors in the room, and the children.

“I stand on the shoulders of relatives who gave everything so I could one day stand up here and say whatever the fuck I want. So I can say, ‘We’re still here.’” “Becoming Little Shell” exists, he says, because people are finally coming to a reckoning.

Winding down, he offers a Turtle Mountain origin story, a story wherein the world is dreamt into existence: Kitchi Manitou, the Great Mystery, sends Nanabozho to communicate with the animals in all their original languages. The first language is listening, he says. The first human task is to be quiet and to remember the language of plants, trees, and animals. To listen. To be in relationship.

The first human task is to be quiet and to remember the language of plants, trees, and animals. To listen. To be in relationship.

We can’t always talk. We’ve got to train in our silence, too, in the choice to, as La Tray says, “inflict my noise upon the world — or not.”

This commitment to relationship, over patient years or generations, might be how we start to make sense of our own fundamental liminality — of the very human quest for identity and belonging. But we have to be willing to listen, commit to the long game, and consider the impact of each choice we make.

It’s less about making a living, perhaps, and more about creating a life. A Good Life that you can be proud of, sure, but also that considers the people that your legacy will touch, those who will one day come into contact with the consequences of your choices.

I think about Stella Nall’s two pink buffalo, presumably on La Tray’s wall at home. The image and its title — ”Stolen Heart” — could be a reference to everything that’s been stolen — land, life, the buffalo themselves — or it could be a commentary on the fragility or risk of interpersonal relationships. It could be a lot of things. Manaaji’idiwin, Buffalo, teaches respect. He also teaches vulnerability, balance, and the often overwhelming responsibility of being an ancestor, or a teacher, or a friend to any other being. And there is care in the image: For the moment, the buffalo with two hearts is at an advantage, occupying a fortunate place of cardiac abundance while the other buffalo deals with whatever symptoms accompany the total loss of a heart. For the moment. The balance is bound to shift but, for now, one buffalo takes care of both hearts. La Tray proposes enduring commitment and care in these moments of imbalance and uncertainty, recruiting us for a long expedition, an adventure with an uncertain outcome, and one that will continue indefinitely for generations: Together, we navigate the darkness, the gnarls of ambiguity, the Great Mystery, and the tangled braids of a big river that cannot, for all its meandering, resist the sea. And we listen.