In coming years, a slated switch of Front and Main streets from one-ways to two-ways will contribute to a significant change to the look and feel of downtown Missoula spanning multiple city blocks.

Why were Front and Main set up as one-ways in the first place? And what’s so wrong with them now?

The answer lies in a car-centric style of urban planning that has become as outmoded as a ‘57 Chevy. Many American cities redesigned two-ways into one-ways to accommodate the comings and goings of newly minted suburbanites.

“The idea back in the 1950s and ‘60s was that downtown one-way street design really emphasized having the capacity for getting people easily in and out in a car,” says Jeremy Keene, director of Public Works and Mobility. “Now, a lot of cities are converting one-ways to two-days to calm down speeds, make them safer, and make them easier to get around.”

City planners identified the need to reconfigure Front and Main as far back as the 2009 Downtown Master Plan, and now the rubber’s finally hitting the road thanks to the the city’s Downtown Safety and Mobility Project securing a $25 million RAISE Act grant last year — one of the largest federal transportation grants ever received in Montana.

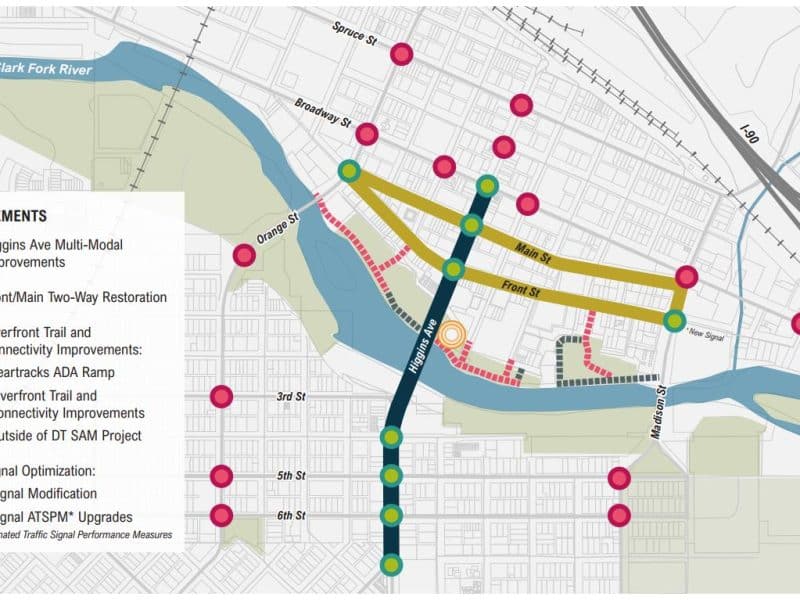

The Downtown SAM Project also includes altering Higgins Avenue from four lanes to three and improving multimodal access to the Clark Fork riverfront.

The Front and Main conversion will significantly reshape multiple access points into downtown, including redoing traffic lights at Orange Street and a curb-to-curb upgrade of the streets to include protection for cyclists and pedestrians.

A feasibility study commissioned by the Missoula Redevelopment Agency 10 years ago suggests two-ways on Front and Main streets will slow down vehicles, improve visibility and boost foot traffic — all to the benefit of businesses.

Incidentally, Montana’s largest city, Billings — a much more sprawling, car-centric metro compared to Missoula — is ahead of the curb, so to speak, in returning its downtown to two-ways. The Magic City approved a plan just this spring to convert more one-ways after completing a conversion on North 29th and North 30th in 2021.

James Chandler, an associate development director with the Downtown Billings Alliance, says the conversion seems to be encouraging more foot traffic and fewer vacant storefronts. “Since converting them to two-ways, especially 29th has seen a big boom in business occupancy on that ground floor level,” he says.

He’s optimistic about the forthcoming conversion of additional streets downtown, and says the short-term impacts from construction didn’t turn into a major issue.

“Any project like this is going to come with some level of headache or teething problems, but we’re a few years into this conversion and it’s been totally fine,” he says. “It took six months and everybody forgot it was a one-way in the first place.”

Today, a growing body of research indicates that urban one-ways often are, to put it simply, not worth keeping. They confuse tourists. They encourage speeding. When it’s easy to zoom away from downtown, drivers are less likely to stop and spend money at shops or restaurants. Cyclists who need to go the wrong direction are encouraged to ride on the sidewalk. Pedestrians have to step out into traffic to see oncoming vehicles.

Back in Missoula, Keene says it’s especially dangerous for pedestrians at intersections when one approaching car stops to let someone pass but the driver in the farther lane doesn’t see the pedestrian and continues at a high speed. Downtown Missoula sees seven times the regional average for crashes, and about 30 percent of injuries reported in downtown traffic collisions are cyclists and pedestrians, according to city staff.

“The best thing we can do is slow drivers down and allow for more time to react, and it creates less severe crashes when they do happen,” Keene says.

The conversion concept also includes separated bicycle lanes and pedestrian bulb-outs, important design features to protect and encourage biking and walking.

“Not everybody can drive, for various reasons. To me, transportation equity is about the opportunity for everyone to get where they need to go,” Keene says. “So that’s one of the driving forces behind this project.”

The Downtown SAM Working Group, made up of 19 community members, meets regularly and is providing feedback to city staff throughout the process.

Committee member Jim Sayer, a former executive director of Adventure Cycling, joined in part to advocate for cyclists and pedestrians.

“I think that for inexperienced and cautious cyclists, Front and Main are not good roads right now,” he says.

The project is still in the design phase, and the preliminary timeline indicates construction could begin in 2026. Follow the city’s updates for the Downtown SAM project at engagemissoula.com.