“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” —Heraclitus

Different men keep returning to the same spot on Missoula’s Clark Fork River, hoping for the same result.

C.P. Higgins built Missoula Mills in 1865 near where the Wilma building stands today. The town grew steadily for a century, until economic turmoil sucked the juice out of its historic heart.

That’s when newspaper publisher John Talbot moved his Missoulian headquarters from 500 North Higgins to 500 South Higgins Avenue, leaving one railroad neighborhood for another just across the river from today’s Wilma. The newsroom has since moved far down West Broadway, abandoning its downtown anchor as the news industry fortunes shrank.

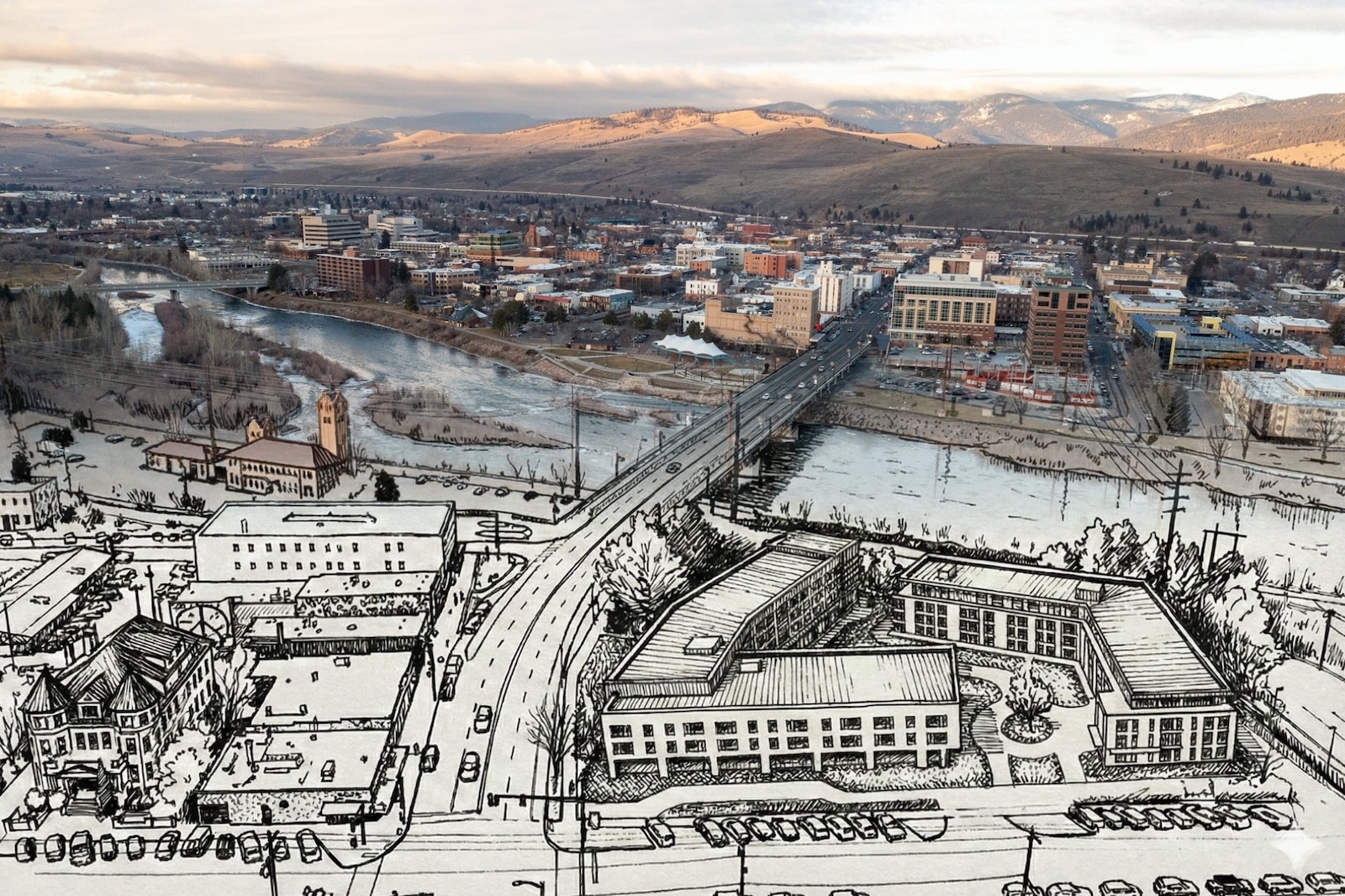

Now a new banner dangles over the Missoulian building’s river-view windows: Higgins Waterfront. The new man looking for rejuvenation in the Clark Fork waters is Cole Bergquist, the University of Montana Grizzlies’ starting quarterback 20 years ago and now a real estate developer. Higgins Waterfront would replace the blighted newspaper office with a two-building, six-story complex of condominiums, hotel rooms, restaurants, shops and offices.

For decades, the Missoulian building was where Missoula’s story got written. Now the property itself is the story. Can it groove to the funk of its Hip Strip neighbors? Will it draw the Garden City’s historic core some new shape or direction? One way or another, a lot of new people will be looking at that reach of the Clark Fork River.

“It’s going to be one of the larger projects in Missoula history that I know of,” Bergquist told The Pulp in a recent interview from his home in Orange County, California. “The site warrants it. This deserves to be the No. 1 development site in Missoula history. It’s the last one of its kind — 10 out of 10 on location.”

“This deserves to be the No. 1 development site in Missoula history. It’s the last one of its kind — 10 out of 10 on location.”

Mills and rails

Missoula’s origin spot was just across the river from Bergquist’s project. Higgins and partners Francis Worden and David Pattee built their lumber and grist mills on the north bank, near the present intersection of Higgins Avenue and Front Street. At the time, the river channel swung farther to the north than today’s corridor.

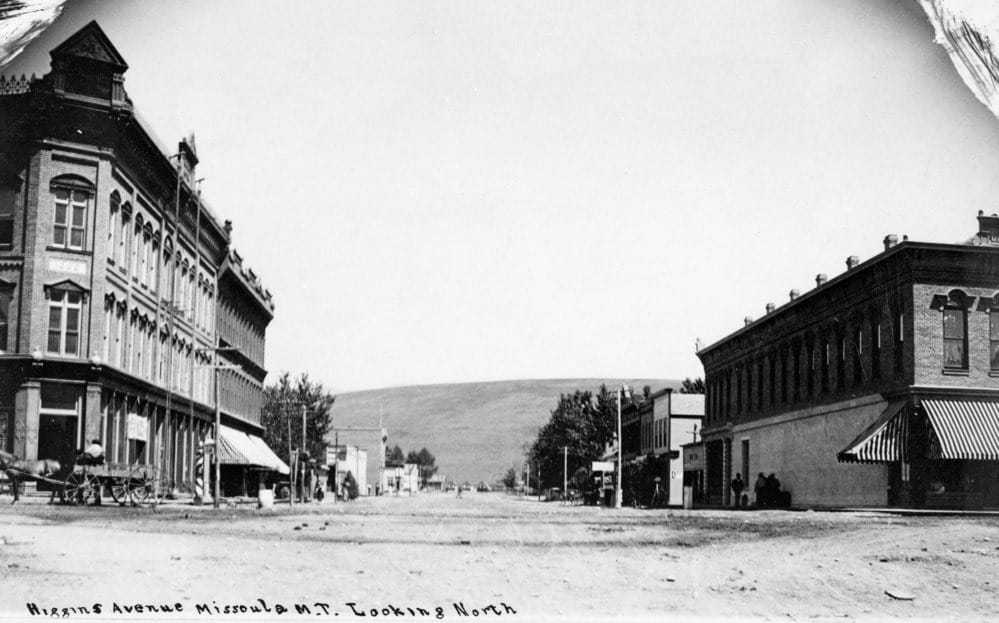

Within a couple decades, that little industrial kernel had sprouted a real town. An 1888 photograph taken from the middle of the intersection showed a four-story Florence Hotel on the west side and the Missoula Mercantile Company on the east, with a wide street stretching north toward Waterworks Hill. The south bank was more hodge-podge, with a mix of private homes and warehouses dominated by Garden City Commercial College’s three-story institution by the turn of the 20th century.

College founder Edward Reitz was competing with the fledgling Montana State College. His school did well enough that when the Higgins Avenue Bridge washed out in the 1908 flood, he was instrumental in raising the $9,000 needed to replace it. A year later, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad laid its railyard and built its Spanish Mission-style depot alongside the new span.

Railroad passengers inspired a lively commercial block on the west side of Higgins, with hotels, shops, candy stores and bakeries. The east side, however, housed the huge tanks, machinery and other backstage trappings of an electric railyard. Up at street grade, H.O. Bell had a car dealership lot.

The railroad went bankrupt and closed the line in 1980, ripping up the tracks for recycling elsewhere. Shortly after its first centennial, downtown Missoula wasn’t doing too great either. Southgate Mall had arrived in 1976, and was exerting enormous pressure on Missoula businesses to join the hot new commercial trend. The historic business district was starting to look like a gap-toothed smile as shops boarded up their windows and moved south. The burghers were trying everything from naming contests (hence “The Hip Strip”) to sponsoring bus service to Anaconda to bring in shoppers.

Ink and paper

Talbot was the Missoulian’s publisher from 1970 to 1980 for Lee Enterprises and continued as a Lee regional vice president until 1986. Carol Van Valkenburg worked with him both at the paper and then at the University of Montana Journalism School. When Talbot died in 2021, Van Valkenburg told me how he had kept Missoula’s historic character alive.

“He was interested in the revitalization of downtown with (former Missoula Mayor) John Toole,” Van Valkenburg recalled. “When Southgate Mall came, that helped the Missoulian tremendously, but John knew that central to the identity of Missoula was the downtown. He was very active making sure it stayed a vital part, while Billings’ and Great Falls’ downtowns were disappearing and being boarded up.”

Jerry Ballas was the Missoulian building architect. He was the son of founding partner Oscar Ballas of Fox, Ballas and Barrow Architects, which also designed the Missoula City Hall, the public library building on Main Street and the University Center on the UM campus. They are all in the “federal modernist” style popular in the mid-20th century, known for a “disdain for ornamentation and fondness for massive forms [that] have sometimes been seen as an expression of efficiency and power — and at other times, as sterile and inhuman,” according to the U.S. General Services Administration. Whatever one thinks about the trend, Ballas did appreciate the river. He stripped the length of the building with windows looking north to the water and downtown.

The Missoula Redevelopment Agency was using tax-increment financing to encourage development by shaving costs off projects, like code compliance or site preparation. Former MRA Director Geoff Badenoch was just starting his career as the Missoulian’s new building was opening in 1985. He said one of its earliest expenses was buying out a big billboard advertising insurance on the south end of the bridge to clear the way for the project.

“The fact that the Missoulian chose this spot was a product of John Talbot being friends with John Toole,” Badenoch recalled. “Those two could pick up a phone and go have coffee and things would happen. The Missoulian could have gone elsewhere, but they chose that spot. They said ‘We’re going to be part of bringing downtown back.’”

When Talbot arranged to move there, the railroad section was broken into three parcels. Lee Enterprises, which owned the Missoulian, took the 3.5-acre chunk next to the bridge and Higgins Avenue. The city got the middle bit and turned it into John Toole Park. Missoula County Public Schools got the third, which became Hellgate High School’s athletic practice field.

The Milwaukee Road pedestrian trail now occupies the former railbed. At the Missoulian site, a line of buffalo junipers hide a set of pre-dug fencepost holes along the trail. Badenoch said the Missoulian initially wanted to fence the entire property all the way to the riverbank, which would have blocked the new trail. The stated reason, Badenoch said, was to be able to secure the property if it had to enforce a union lockout. A pile of chain-link rolls were kept in a storeroom in the basement. Those pre-dug holes would allow the Missoulian to erect a fence in a couple hours if needed.

“John Talbot and John Toole could pick up a phone and go have coffee and things would happen. The Missoulian could have gone elsewhere, but they chose that spot. They said ‘We’re going to be part of bringing downtown back.’”

The little park between the trail and an irrigation canal had a series of humps for visual relief. MRA imagined they might have been used for BMX bikers. Instead they were popular with daycare children, and college kids who came to make out in the summer. Missoulian staff would watch from the windows when especially horny couples would get going. We often considered getting big score cards so we could rate performance from the upstairs windows like Olympics judges.

The building itself was a 56,000-square-foot fortress. The place literally hummed with activity, with the double-decked Goss printing press roaring in the basement and the clattering carousel of sorting machines fitting all the daily newspaper sections together in the mailroom. Just inside the doors were wall-mounted ear-plug dispensers three times the size of the Lion’s Club bubblegum machines in the lobby.

The building hummed, but it didn’t rattle. That’s because, according to the mechanics who tended that big red press, the foundation had been poured extra-thick to withstand the vibrations of its action. Although the Missoulian building was only two stories tall, that substructure was allegedly sturdy enough to support a tower as tall as the eight-story Millennium Building across the river. It had its own unique city zone allowing its mix of heavy machinery, chemicals, commercial activity and transportation needs.

Full disclosure: I spent the bulk of my journalism lifetime at 500 South Higgins. For a few days, I had the second-best office in Missoula. The best was directly above, where the Missoulian publisher sat. It had a view of the river and an executive toilet.

The Missoulian managing editor’s desk was on the lower floor, looking out at a patio, bordered by an irrigation canal, leading to the little knobby park, and then the Clark Fork River. I never actually used it, as my promotion to newsroom leadership happened just as Lee Enterprises was completing the sale of the building to Bergquist for $8 million.

The hollowing-out of 500 South Higgins Avenue had been going on for years. I first came to work there in 1987 as a freelance reporter. One assignment was to help compile an annual Missoula business report, which noted that the Missoulian was one of the biggest employers in town. At its height, 160 full-time and 45 part-time workers rattled around there. When we moved to a new office on West Broadway in 2021, there were 75, including 21 in the newsroom.

Glass and steel

When then-Missoulian Publisher Jim Strauss announced the building’s sale in 2020, he recalled its significance to downtown’s character. “People ask, ‘why are we selling’ and well, blame it on the Clark Fork,” Strauss told Missoulian reporter David Erickson. “It’s such a beautiful piece of property. We really aren’t tapping the full potential of the property.”

Historically, attitudes had been just the opposite. On the north bank, where Orange Street crosses, was the city dump. For decades, the only business that made the corridor an asset was the Edgewater, now Double Tree Hilton Hotel, by the Madison Street Bridge. Virtually every other major property — Eastgate Shopping Center, University of Montana, Front Street businesses — turned its back to the water.

“People ask, ‘why are we selling’ and well, blame it on the Clark Fork.”

Cole Bergquist grew up in California and came to Missoula for college and football. He lived here 15 years, including his time as the star quarterback for the University of Montana Grizzlies, and then as a real estate salesman. He moved back to San Juan Capistrano seven years ago, he said, so his children could be closer to their grandparents.

In 2020, he leveled up from real estate sales to real estate development. He led the Reed Apartments project just a block east of the Missoulian on Fourth Avenue. When Lee Enterprises decided to sell the Missoulian building in 2021, he jumped at the chance to buy it.

Bergquist’s initial plan in 2022 envisioned 80 to 90 apartments, the same number of condominiums, 40 to 70 smaller housing units and an underground parking garage able to hold at least 250 cars. It also had a central plaza, street-level commercial spaces, and a park along the riverbank.

“We didn’t want to be constrained to the footprint of an old building designed for a newspaper press,” Bergquist said in a January 28 interview with The Pulp. “It doesn’t give you much freedom. A year and half ago, we had an 11-story building designed. In Missoula, that’s really hard to get those to pencil.”

The project hit a different kind of problem shortly after announcement, when Bergquist’s business partner, Aaron Wagner, got in a digital tarpit after he made a series of obscene and vulgar responses to critics on social media in November 2021. Wagner publicly apologized and backed away from public view. But then, in 2024, he was arrested and indicted on 16 counts of wire fraud and money laundering after investigators showed he had scammed investors out of $40 million to pay for private airplanes and other personal benefits. Wagner has pleaded not guilty.

Bergquist then teamed up with Boise, Idaho-based Hawkins Companies. The firm claims a nearly 50-year history of experience in multi-family, retail, charter school and hotel development. Requests for comment from Hawkins were not returned.

Bergquist declined to state a project price, but said the previously reported $100 million figure was still “accurate.” Raising that runs tandem with the architectural and permitting processes.

Higgins Waterfront hasn’t submitted any formal plans for review, according to Missoula Community Planning, Development and Innovation Department Deputy Director Walter Banzinger. The property would likely be included in the Downtown Core and will be subject to the city’s new zoning and land use standards that just got approved on Feb. 2.

“If it meets code verbatim and they aren’t asking for any changes, there likely wouldn’t be any public process,” Banzinger said of the Higgins Waterfront permitting procedure. “But we don’t know what they’re submitting at this time.”

Because the old newspaper headquarters will be scrapped for the new complex, the old unique zone will almost certainly need updating. And that would trigger public scrutiny.

“We’d love to start in 2026, but I could see it getting pushed further than that,” Bergquist said. He’s aware of the saga of the Riverfront Triangle, downtown Missoula’s other bridge-side redevelopment project that’s been announcing elaborate development plans every few years since it was cleared in 1998. Each failed to attract enough investors to launch.

“The biggest hurdle on a project like this is frankly just raising the capital,” Bergquist said. “Missoula is an interesting, tertiary market. This is a big-ticket project, but not necessarily something that would automatically attract a high-net-worth individual or institutional funding.”

The latest Higgins Waterfront conceptual designs put a restaurant along the bridge where the publisher used to sit. My office would become a walk-out hotel suite, one of 155 rooms managed by a to-be-named hospitality firm. Another building would have 80 residences, mixing single-floor condominiums with two-story townhomes. A rooftop bar would overlook the whole scene, fully enclosed for winter use.

The project’s street side should mimic the Hip Strip’s line of street shops. Bergquist said he’s received interest ranging from optometrists to yoga studios. While he said he knows several of the developers who plan major changes across the street, he’s not coordinating or partnering in any of those projects.

“The Hip Strip already has such a steep tradition,” Bergquist said. “This will just accentuate that.”