Photos by John Stember

Missoula doctors Jennifer Mayo and Amy Smith zipped across town on Oct. 10 through midday traffic, keenly aware they were already running late for a bittersweet appointment. They’d just admitted the first patient to their new digs at Community Medical Center, but across town, their colleagues at St. Patrick Hospital’s Family Maternity Center were waiting for them. After years of helping bring newborns into the world, neither physician wanted to miss the unit’s last lullaby.

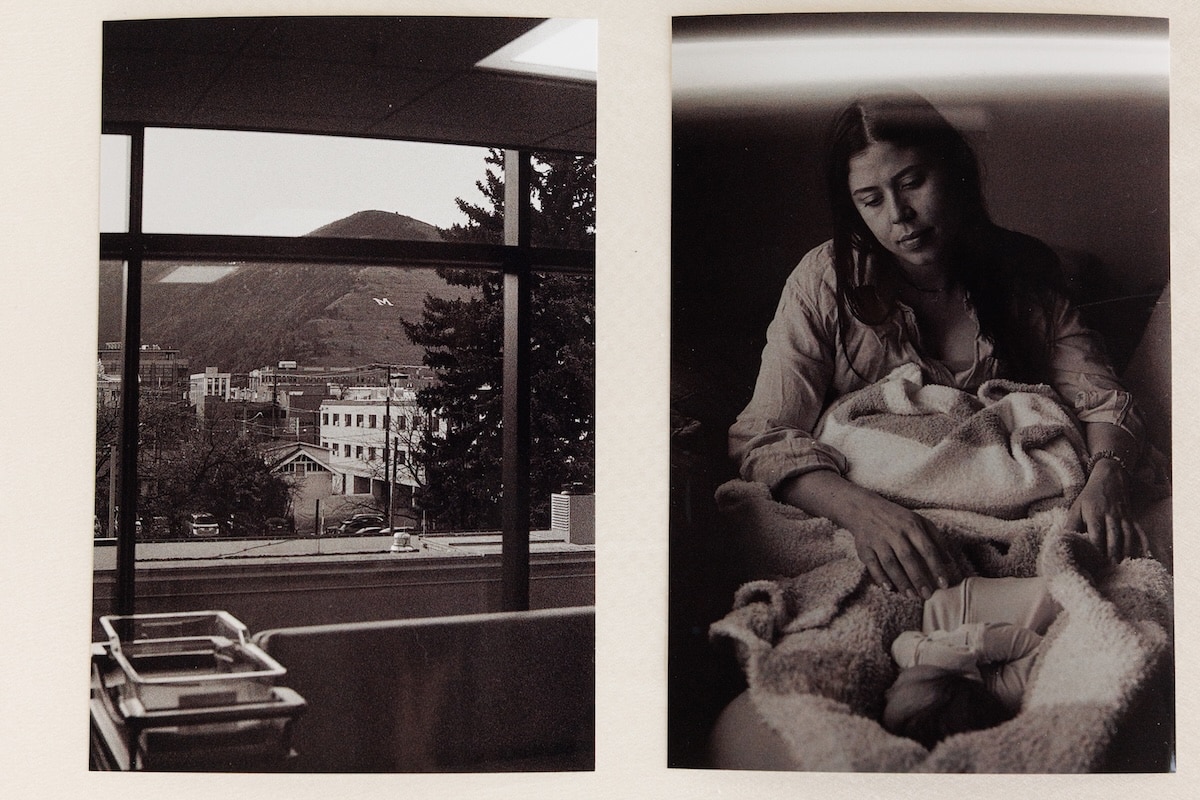

When they arrived at the cluster of third-floor delivery rooms overlooking Missoula’s downtown and eastern hills, they joined the two dozen nurses and doctors already gathered in the hallway. Then came the chime: A tinny, electronic version of “Hush, Little Baby” they’d heard countless times before. A melody that had signaled to everyone across the St. Pat’s complex the arrival of a new baby. But this time was different. There was no baby — only a broadcasted prayer, the chime, and an atmosphere that some of those present likened to a wake.

“We just all passed Kleenex around and had our moment, which was really lovely,” Smith told The Pulp. “I think it needed to happen in a way that gave everyone closure for this trauma, the trauma of going through this experience together.”

Roughly four months prior, in early June, St. Pat’s administrators announced they were shuttering the 10-year-old labor and delivery unit due to “external challenges.” The announcement was unexpected and sudden, and it struck the community like a thunderclap.

“It is clear that to corporate medicine, we are each just a cog to be removed and replaced with any credentialed provider.”

For the center’s staff, closure meant an end to a specialized space they’d spent a decade diligently cultivating. For families in the region, it meant one less trusted place to go for assistance, education and care. And for the Missoula community at large, it raised questions about the manner in which decisions impacting the health of local residents are made. Some were outraged, others dumbfounded, and it didn’t take long for health care professionals to voice a mixture of criticism and concern over the loss of a clinical setting not easily replaced.

The center’s doctors, who are part of Missoula’s physician-owned Western Montana Clinic and had privileges to work at St. Pat’s, quickly brokered an arrangement with administrators at Community Medical Center to relocate their services across town. Yet even months later, affected providers have continued to question the handling of the closure, with Mayo asserting in an October letter to St. Pat’s administrators, board members and the umbrella Providence Health System that the situation showed a “casual disregard for those who serve their mission.”

“Your hospital is devastated to lose [obstetric and gynecological] services, and the care we provided across service lines, cultivated over a decade, as a team. It is clear that to corporate medicine, we are each just a cog to be removed and replaced with any credentialed provider.”

After the last lullaby was over, the entire crew of St. Pat’s Family Maternity Center save one — Dr. Janice Givler, who was out of the country at the time — stood together in shared frustration and grief. There were speeches, tears, hands placed on shoulders. Then Smith, Mayo and their compatriots began to make their way toward the door for a planned group photo on the rooftop helipad, unaware, Smith said, of a final surprise waiting outside.

Both sides of the hall were lined with patients, parents, children and babies born at the center, and on-shift hospital staff who had temporarily stepped away to show their appreciation. They clapped and cheered. A few clutched a banner signed by health care providers throughout the Missoula community thanking the center’s staff for a legacy of “care, compassion and new life.”

“You just don’t ever get the opportunity to open a new unit. It’s so incredibly rare. It was a huge leap of faith. There was a lot of doubt that we would succeed, that we would do well.”

“They had kazoos or something, noisemakers, so it wasn’t all sad,” Mayo told The Pulp, adding that, prior to that moment, she’d felt a need to remain stoic. “People were crying and clapping and giving hugs. That actually made me fall immediately. I could probably cry just talking about it.”

The celebration served as a collective reminder of the reputation staff had helped build at St. Pat’s over the past decade. And in the weeks since, the silence that’s followed St. Pat’s final birth chime has continued to spark reflection among doctors, nurses and Missoula families — about what the center’s closure means for local health care, and about the lasting imprint of the center’s 10-year presence in the region.

On July 29, 2015, St. Pat’s unveiled the results of an extensive $5 million remodel on the third floor of its sprawling Broadway Building designed to get the hospital back in the business of delivering babies for the first time in 40 years. Administrators touted the sleek, state-of-the-art unit as a revival of full-service care at St. Pat’s, a place where mothers could give birth and recover in a single private room with access to a full range of medical support and educational resources.

Joyce Dombrouski, then the chief acute services officer at St. Pat’s, told the Missoulian that the hospital had gone to great lengths to create effectiveness, efficiency and “the right experience for the moms,” and news stories made special note of the birth of the first baby at St. Pat’s since the hospital halted labor and delivery services in 1975.

Mayo was among the first OB-GYNs to work in the new Family Maternity Center. She and her fellow physicians at Western Montana Clinic had heard about St. Pat’s interest in relaunching such services early on, while still working out of the birth center at Community. Mayo said the prospect of adding more obstetrician-gynecologists to the local workforce stirred concern among Missoula’s existing labor and delivery specialists. And so, with St. Pat’s set on forging ahead, she, Givler, and another colleague agreed to move their services across town, to the new center.

“We could have said no and let them just do their thing and not be involved, but it felt like we already had relationships there that were good, both with the administration and with the physicians, and so it made sense,” Mayo said. “Once we were like, ‘Okay, I guess we’re doing this,’ then it became exciting.”

In addition to providing family-centered maternity care in spacious new quarters, Mayo noted the team’s surgical practice grew “dramatically,” doubling its number of operating days per month. The unit quickly built a reputation as a venue for high-quality gynecological surgical care, its services bolstered by St. Pat’s regional status as a high-level trauma center capable of handling nearly any kind of serious injury around the clock. And on a more personal level, Mayo and others felt the Family Maternity Center gave them an opportunity to create a space and a team that reflected their values as providers.

“You just don’t ever get the opportunity to open a new unit, it’s so incredibly rare,” said charge nurse Megan Carey, who left Community Medical Center in 2015 to join the founding crew at St. Pat’s. “It was a huge leap of faith. There was a lot of doubt that we would succeed, that we would do well.”

Opportunity was what lured Amy Smith to the center too, after completing her residency in Utah in 2020. Smith, who was born in Missoula, said the setup at St. Pat’s ticked all the boxes she was looking for as a young OB-GYN, from the size of the community to the levels of care the facility specialized in. That, she continued, made it all the more difficult to find out it was all coming to an end.

According to multiple sources interviewed for this story, rumors of a potential closure first cropped up in fall 2024 but were quickly squelched by the administration in a meeting with Givler. The official announcement didn’t come until June 3, when Givler was called to a meeting with St. Pat’s CEO William Calhoun and informed the center would be closing in October. Sources said that Givler was the only center representative to receive such notification, and that many others only learned of the closure through word of mouth.

Within hours, the news spread to nurses and patients and was later confirmed by Providence in a public statement. The statement attributed the decision to “flat and declining birth volumes, and workforce shortages,” and assured that Western Montana Clinic and Community Medical Center would provide a “seamless transition of care for expectant mothers.”

“This decision was not made lightly and was guided by our commitment to providing high-quality, compassionate care to our community while being good stewards of our resources,” Providence’s announcement read, adding Community’s ability to “meet current and future market needs” would prevent any decline in access to quality services.

In a Nov. 3 email response to questions from The Pulp, Providence Montana Chief Nursing Officer Krissy Petersen reiterated that the excellent care provided by Western Montana Clinic’s physicians would continue, and expressed gratitude for the compassion and dedication they displayed during their tenure at St. Pat’s. Petersen also noted that roughly a third of the care team from the Family Maternity Center would remain with Providence in new positions, and the former center space will be used to expand existing critical care needs in the hospital.

“The vacated space will be converted to add critical care capacity,” Petersen wrote of the center’s physical future, “increasing our ability to provide essential access for higher-acuity patients and decompress our current inpatient areas.”

“Trauma happens, and those patients are going to need the critical services of the trauma teams that St. Pat’s provides.”

The Family Maternity Center’s team was stunned by the decision, and Carey described the ensuing weeks as punctuated by grief and anger. Staff characterized the decision in interviews as lacking transparency or open engagement with the community, a stark contrast to the high-profile planning and discussions Mayo recalled around the unit’s establishment. And the narrow timeframe announced by St. Pat’s had Mayo and other physicians working fast on a strategy to ensure post-closure delivery space for dozens of existing patients.

“We had a lot of patients that were pregnant that we would have been abandoning if we didn’t immediately apply for privileges at Community, because they wouldn’t have had a place to deliver if we weren’t able to move across town with them,” said Mayo, who was told of the closure while in the operating room on June 3. Mayo estimated that at least 150 expecting mothers would have been affected had Western Montana Clinic and Community not brokered an arrangement so quickly. She added that count doesn’t include scores of other patients who came to St. Pat’s for non-birth-related gynecological care.

In an email statement to The Pulp, Community Medical Center CEO Greg Cook confirmed he and other administrators began working with physicians and patients immediately after learning about plans for the closure. He said that Community was grateful for the opportunity to preserve the expertise and compassion that defined the center, and that the move to do so aligned with Community’s longstanding focus on maternal care.

“We were glad to collaborate with physicians and staff from Western Montana Clinic and Providence St. Patrick Hospital to help create a smooth transition for patients,” Cook wrote. “Our priority throughout this process has been maintaining continuity of care for expectant mothers and supporting the doctors and clinicians who serve them.”

The closure also illustrated for Mayo a broader tension within America’s health care system, where business decisions made in the interests of resource costs or demand may not align with what medical experts see as the best provision of care for a community. Health care has shrunk across much of the United States in recent decades with the closure of scores of rural hospitals — 184 nationwide between 2005 and 2021, according to Montana health department researchers. An even greater number of rural obstetric units have shuttered, shifting such care to larger regional care centers like St. Pat’s. Smith said she saw pregnant patients from as far away as Helena, Great Falls, Dillon, De Borgia and Salmon, Idaho.

It’s not that the move back to Community is in any way a detriment, Mayo said. The hospital already had a robust labor and delivery unit, and patients will continue birthing healthy babies there under the care of existing staff and those relocating from the Family Maternity Center. But Community, by design, doesn’t have the same round-the-clock crisis resources or capacity as a level II trauma center. Without St. Pat’s obstetric unit, families in the region lose another place to get specialized care, and the hospital loses a team whose expertise can be critical when young families face a crisis.

“St. Pat’s can handle a lot of things, and the access to that trauma service is going to trump the access to maternity care,” Smith said, referencing the trauma designation that makes St. Pat’s the area’s de facto facility for handling significant crisis-level events. “Women fall, car accidents happen. We also live in a state where women who are pregnant ride horses, ski, are on four-wheelers for just their normal daily activities. Trauma happens, and those patients are going to need the critical services of the trauma teams that St. Pat’s provides.”

Delivery was going well at the St. Pat’s Family Maternity Center this year for Joelle Parks and her husband, Devon Dietrich. Despite the anxiety that comes with a first pregnancy, the couple had received months of reassurance from Mayo, the same doctor who had delivered three of Parks’ brother’s children. They described her as warm and welcoming, adjectives they quickly extended to the entire center staff and the setting itself.

Both University of Montana graduates now working in tech, Parks and Dietrich met in Seattle through the UM Alumni Association and moved back to Missoula — Parks’ hometown — with the goal of raising a family. From a comfortable room overlooking Mount Sentinel and the campus of their alma mater, Parks prepared for the final series of pushes and it looked as though they’d be taking that leap into parenthood in no time.

Then, Parks told The Pulp, her umbilical cord prolapsed.

“I don’t even remember pushing a button or calling,” Parks said. “Everybody on the floor of the [center] came running in to support. He was losing oxygen and his heart rate completely dropped, and they were pushing his head back in to keep him breathing.”

Mayo immediately made the call to rush Parks to the operating room, Dietrich continued, in order to be prepared for any additional complications. As Parks began to cry, Mayo clutched her hand and offered a few words of reassurance, then sprinted down the hall to scrub in. Another physician, Janice Givler, arrived to assist, and Parks recalled that before she was “knocked out” for an emergency cesarean section, she was able to share a poetic bit of information: she’d been one of Givler’s first solo deliveries 31 years ago when Givler first started as an OB-GYN.

“It was full circle,” Parks said. “It was crazy.”

The situation was everything both parents-to-be had been dreading: an unexpected and life-threatening development requiring immediate surgical intervention. Sitting in a chic modern living room off Mullan Road with their six-month-old son, Beckett, the couple consider themselves lucky for the level of care they had access to. And not long after Beckett’s birth, when Parks went to the St. Pat’s emergency room with an infection below her C-section scar, she and Dietrich feel doubly lucky that the Family Maternity Center staff stepped in again. They readmitted Parks to a vacant room for a week after her follow-up surgery, allowing her and Dietrich to continue caring for their infant together.

“When we were wheeled up there that night from the ER, the entire staff was just waiting to catch us, both physically and metaphorically,” Parks said.

“When we were wheeled up there that night from the ER, the entire staff was just waiting to catch us, both physically and metaphorically.”

Emergencies aren’t uncommon in pregnancy and childbirth. Labor nurse Cassidy Dillon said she’s been in scenarios where a mother started bleeding mid-delivery and within four minutes, the baby didn’t have a heartbeat. Sometimes seconds count, and Dillon’s biggest concern over the center’s closure is the impact on the speed and scope of care. Especially given the decline in rural obstetric care, she said, parents may Google local hospitals and arrive at an emergency room completely unaware of what resources or specialists are actually on hand.

“Potentially losing my child in a modern, first-world country is terrifying,” said Dillon, who was able to transfer to a nursing position at Community Medical Center. “And it’s so, so sad because it is so preventable.”

Prior to her first delivery in 2020, LeeAnne Rimel said her visits to the Family Maternity Center grew increasingly frequent through her third trimester as her anxiety about potential problems grew. Nurses and physicians validated her feelings as a legitimate part of pregnancy, while also reassuring her that she and her baby were healthy. And when complications did set in an hour or so after an unplanned C-section, Rimel said the facilities and the fast response at the center were everything.

“I crashed,” Rimel recalled. “I had a massive drop in my blood pressure and I required a massive transfusion protocol and an emergency surgery. It was one of those things where very quickly there were, like, 20 people in the room.”

Rimel described it as one of those one-in-a-million emergencies, an internal bleed her doctors and friends in the medical community told her was exceedingly rare. But it happened, and as she remained in the St. Pat’s ICU post-surgery, the Family Maternity Center team took steps to visit with her infant daughter so mother and child could forge an early bond. Everything she witnessed told her the center and its staff treated patients and colleagues alike with the utmost respect and care, even in moments of intense pressure. And when, four years later, Rimel and her husband decided to have a second child, she said Mayo and the other physicians helped put her mind at ease, reassuring her that the experience of her first delivery was extremely uncommon and that “there wasn’t any reason to believe it would happen again.”

“I think my experience made me feel more attached to the center,” Rimel said, “that I felt like I had this more unique medical history, and I felt like all of the nurses and all the physicians there knew.”

For this reason, the Family Maternity Center’s closure deeply affected the families who’d experienced unbridled joy or unmatched sadness within its walls. Physicians and nurses had helped calm their anxieties, had seen them through sudden and fraught situations and guided them on their first steps as new parents. Parks and Dietrich recalled that even the man who cleaned their room each day and brought them fresh towels left an indelible mark on them, leaving small handwritten notes of inspiration that they’ve kept as mementos.

“Having such an intimate relationship with all of the staff, it feels like it’s hard not to look at it from a personal level and recognize the impacts on not just these providers as care providers but as human beings,” Dietrich said.

In recent weeks, Mayo and the Western Montana Clinic physicians have been settling into their new office space on the Community Medical Center campus. It’s not as big, she said, but other physician groups were willing to move around to accommodate the relocation, and colleagues at the hospital overall have worked hard to help the former center crew continue their work. Even though Community doesn’t, by design, boast the same level of trauma response as St. Pat’s, Mayo also noted it was fortuitous that on the day she approached administrators about the closure in June, Community had just wheeled in their second surgical robot.

“They doubled their [operating] capacity at the time we needed,” Mayo said. “That really worked in our favor.”

Doctors, nurses and former patients interviewed for this story all agreed that the move to Community means the quality care delivered by professionals at the Family Maternity Center will continue. All but one of the center’s physicians will now be working out of Community’s facilities, and several of the nursing staff were able to make the move as well, though with the labor and delivery unit already staffed, not all found identical positions. More than 100 expecting mothers who thought they’d be giving birth at St. Pat’s will still have a place in Missoula to deliver, even if the experience isn’t quite the same as it would have been in the center’s rooms.

What universally stuck out in interviews about the closure was the message it sent about women’s health care in the community. Sources framed it as a narrowing of the options available for obstetric and gynecological services. Now women seeking specialized services have one less hospital on their list, one less option to choose from, one less space to seek care and reassurance.

“Moms in Missoula deserve choices,” Rimel said, “and they deserve the ability to think about what’s important to them, what ties to their goals and values with their care, and to find providers that tie to those values.”

The center’s staff also reflected on what the loss of the center will mean for the remainder of the St. Pat’s community. With the birth chime now silent, Mayo wondered if the hospital will continue its parallel practice of playing a death chime when a patient passes. Hospitals are often places of immense pain and grief, Smith said, and the presence of a suite dedicated to new life felt as though it brought balance. Dillon echoed the thought, speculating that the loss was partly what made the last lullaby on Oct. 10 such an emotional moment for everyone.

“I think the maternity center was kind of a shining light,” Dillon said, “in a very dark place.”