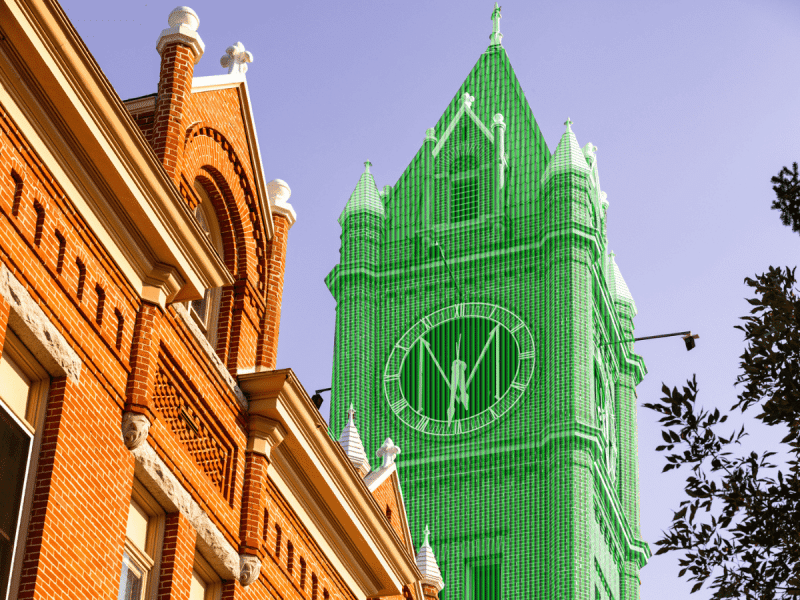

In a grassy backyard in central Missoula, a dozen toddlers race around jumbles of play equipment, their squeals echoing off the wall of a small green house. Inside an adjoining former office building, a woman in flowing clothes reclines in a rocking chair, one sleeping infant clutched to her chest, another stirring occasionally from a nap a few feet away.

For more than five years now, Little Twigs Childcare has been meeting the needs of a growing number of Missoula families with children too young to enter the public school system. Today the center, one of just over 100 licensed providers in the county, supplies daylong care and instruction to around 85 kids 4 years old and younger, enabling their parents to earn a living in an era of constantly rising costs. Caiti Carpenter, a local attorney whose two children have both attended the center, credits Little Twigs and its 33 teachers with not only allowing her to work and support her family, but with helping guide her as a new mother.

“I get emotional thinking about it,” Carpenter said, stifling tears in an interview. “I didn’t have people to show me how to be a mom. They did.”

As poignant as their role has been in Carpenter’s life, it comes with a painful irony: many of the child care workers who are so essential to guiding families like hers through early childhood can’t afford child care for their own children — not without support. Roughly a third of the Little Twigs’ staff this year have been relying on a federally funded subsidy program to help pay child care costs for their own kids. But that program is set to expire by December, and a bipartisan bid by state lawmakers to continue such coverage with state dollars was stymied this summer by a veto from Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte. Now, hundreds of participants stand to lose access to a source of aid that’s helped make their work in the child care sector pencil out.

“They don’t have to pay more than $100 per month for their own child care,” Little Twigs founder and co-owner Marmot Snetsinger said, adding several of her staff currently participating in the Child Care Assistance for Child Care Workers program still had not received formal notification in early October that it was ending. “It really makes it an affordable way to be at work and stay in the profession of child care and have your own kids in care.”

Montana launched the program in October 2023 as part of a multi-pronged early education initiative, dubbed Bright Futures, aimed at directing federal grant money toward recruitment, retention, slot expansion and other issues tied to Montana’s child care crisis. The rising cost of care has become a growing challenge for working families, a reality that can manifest in delayed career goals, chaotic daily schedules, frayed relationships and a patchwork of near-term solutions involving family, friends and an array of community-based programming.

That picture often looks considerably bleak within the child care industry itself, where tuition has rapidly outpaced wages for child care workers. According to state data, the average wage for a child care worker in 2023 was just under $13 an hour; the weekly cost of child care per household, meanwhile, averaged $350.

The child care worker assistance portion of the Bright Futures initiative leveraged the state’s existing income-based Best Beginnings scholarship, using federal funds to lower the eligibility threshold for child care workers and cap their copays at $100 per month. Montana’s Department of Public Health and Human Services reported to lawmakers earlier this year that more than 300 workers had received $2.5 million in financial assistance through the program between October 2023 and June 2024.

“It’s been critical to have this program to keep my most experienced staff, the people that I’ve been training for years, to keep them employed.”

Caitlin Jensen, executive director at the Helena-based early education nonprofit Zero to Five Montana, said those dollars also benefited the child care businesses employing those workers, often enabling providers to pay for projects they may not otherwise have been able to afford.

“My own provider here in Helena, I remember her mentioning being able to have that covered for one of her staff members meant that she could work on a major fence improvement in her facility,” Jensen said. “It just helps to offset some of those costs, and I think that was the opportunity and part of the promise of what we’ve heard from all across the state is that this really does help with business sustainability.”

Now the spigot is shutting off in the coming months. According to DPHHS spokesperson Jon Ebelt, the worker assistance pilot was always designed to end in December 2025 due to the three-year life of the federal grant supporting it. Ebelt added via email that current participants will continue to receive the subsidy through December, and that all participants were notified of the pilot’s end on July 28.

“It was also communicated that, as of July 31, 2025, we were no longer able to accept new applications for this federally-funded program,” Ebelt wrote. “We want to be clear that this change is due to the end of the federal program’s grant funding.”

In response to a records request for more up-to-date information on program outcomes, Ebelt added that data on total participants and total funding utilized will be compiled after the program fully closes down .

Child care providers and advocates had been confident the state would continue funding assistance on its own after the 2025 Montana Legislature passed House Bill 456 with strong bipartisan support. The measure, carried by Missoula Rep. Jonathan Karlen, a Democrat, would have automatically qualified most of Montana’s child care workforce for the Best Beginnings scholarship, which is currently only available to households making less than 185 percent of the federal poverty level. According to Jensen, Montana was among 18 states to consider such legislation since 2024, and among seven who approved it.

But HB 456 fell to Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte’s veto pen in June, with the governor noting it would cost taxpayers $21 million over the next four years and suggesting the separate passage of a $10 million state trust fund for early education provided ample money for innovation. Gianforte has yet to announce appointees for the new 10-member board charged with overseeing that trust, and his office’s boards and appointments webpage was still soliciting applications for nine board openings as of Oct. 6.

Absent continued support, scores of child care workers statewide now face significant increases to their own monthly child care expenses — in some cases, allegedly, without warning.

Snetsinger told The Pulp that as of Oct. 7, several of the 11 Little Twigs employees participating in the program still had not received formal notice from DPHHS that their subsidy was ending. Three of those child care workers confirmed as much in direct conversations with The Pulp last month, stating that they have been scared, confused and unsure exactly when their monthly child care costs will increase — or how they’ll afford it when they do. Many of the women on Snetsinger’s staff are also from refugee families working legally to carve out a new life in the Missoula community, raising additional challenges when it comes to their familiarity with and access to resources.

“Thirteen hundred bucks a month, they can’t afford to pay that out of their salary. It just doesn’t make any sense for them to keep working.”

Snetsinger noted that the program’s expanded income eligibility was particularly beneficial in helping retain her more experienced “lead teachers,” whose pay puts them above the standard Best Beginnings threshold but who would still be unable to afford the full monthly tuition Little Twigs normally charges.

“Thirteen hundred bucks a month, they can’t afford to pay that out of their salary,” said Snetsinger, adding her starting wage for lead teachers is $18 an hour — three dollars more than her wage for an entry-level child care worker. “It just doesn’t make any sense for them to keep working. So for me, it’s been critical to have this program to keep my most experienced staff, the people that I’ve been training for years, to keep them employed and working and able to pay them a decent raise for the work that they do.”

Snetsinger added that while some providers offer employees free or reduced rate tuition, the “razor thin margins” associated with the child care business make such arrangements extremely challenging to calculate or shoulder. She said she’s working to do everything in her power to help her employees weather the current uncertainty and potential future cost increase, including working to strategize and promote fundraising dinners cooked by Little Twigs employees to help cover their individual needs.

As both a Little Twigs parent and an outspoken advocate of HB 456 during the 2025 session, Carpenter said she just can’t understand the political winds that resulted in a looming assistance cliff for the teachers she’s relied on so heavily for so much.

“Just talk to any parent in the state of Montana, I swear to you, they will say the cost of child care is too high,” Carpenter said. “And I wish I could pay more, because these people do a great job.”