On May 7, Steve Albini—a Missoula high school graduate and one of the most influential people in the history of indie music—died unexpectedly from a heart attack.

Broadly speaking, Steve Albini did not give a shit. He did not care what you, a random person, might think. He often said that explicitly and implied it in many other ways.

He did care, though. He was fanatical about music, specifically the nexus of music, art, aesthetics and ethics. He cared about details: about how to properly mic a kick drum, for example. But also about big ideas, like how communities support art and how commercialization stifles art. And he cared, despite his reputation as a misanthrope, about people—particularly other musicians, artists and outsiders, but he also cared about humans more broadly.

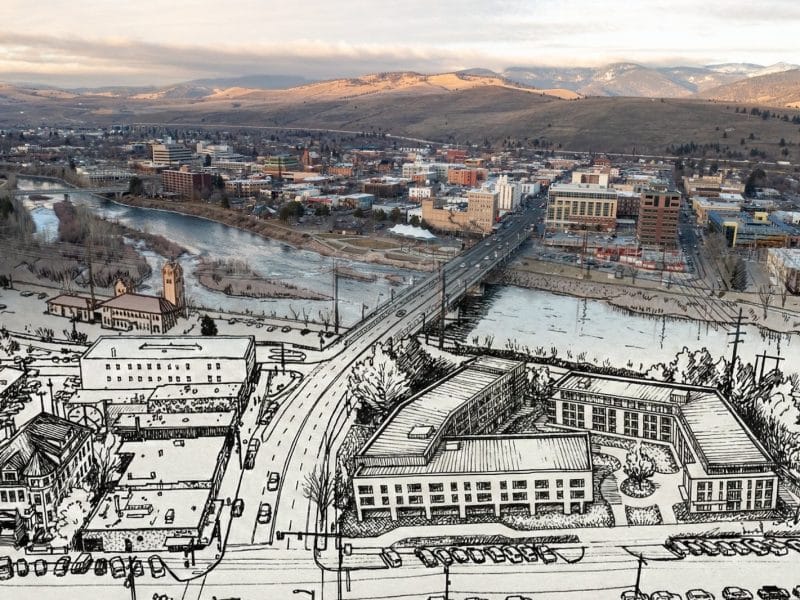

Albini did not live very much of his life in Missoula, but his fanaticism—his deep and diverse passions and interests—bloomed during his years here. And despite decamping from Montana at his earliest chance, he continued to have strong connections with Missoula and Montana.

Multiple publications, from The New York Times to Pitchfork and Rolling Stone, have memorialized Albini since he died. But, even before his death, his approach to music and life have periodically been the focus of major stories, including a 2023 Guardian article on “The Evolution of Steve Albini.” Here are some of the essentials of his career: In the early 1980s, he formed the seminal industrial-noise-punk rock band Big Black. He also began recording other underground artists: the oscillating murmur and scream of Slint, the pummeling grunge of Tad, and the ominous yowlings of the Jesus Lizard. Albini disdained the idea that he “produced” any band’s music, but he took pride in his deep knowledge of the technical details of analog electrical recording, and he used that knowledge to meticulously capture the sound of a band.

Albini’s reputation grew, and extended outside the punk/indie underground, after he helped the Pixies record their 1988 album Surfer Rosa. Three years later, Nirvana’s album Nevermind bulldozed away an era of hair metal and backfilled it with an array of grunge and alternative rock bands. Attracted by Albini’s approach to recording and his punk rock credibility, Nirvana asked him to produce their next record, In Utero. Albini was game, under one condition that he outlined in a letter to the band: “I’m only interested in working on records that legitimately reflect the band’s own perception of their music and existence. If you will commit yourselves to that as a tenet of the recording methodology, then I will bust my ass for you.” He also refused any royalties on the record, finding it unethical to make money in perpetuity off what he considered the artistic product of a band.

Albini’s work on In Utero brought him yet more fame, which he did his best to brush off. He continued to record hundreds of indie bands at bargain rates and churn out brutal noise music with his new band Shellac.

All the while, Albini shot his mouth off. Today, when young people (or anyone, for that matter) broadcast any ill-conceived thought through social media, they enter it into the public record, sometimes forever, and in ways that can haunt them with regret later in their lives. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, when Albini was pretty young, that wasn’t the case. But one exception was zines, small, do-it-yourself publications heavily associated with the punk underground. In the pages of Forced Exposure, Matter and other zines, a dedicated writer like Albini (who majored in journalism) could fill up a lot of column inches with ideas. For better or worse (and frequently for worse for Albini), much of his deliberately provocative writing from his twenties has been preserved.

Albini was a dedicated provocateur in his writing and his music. In both forms, he could be creative, funny, conscientious and smart. His most famous essay, published in 1993 as “The Problem with Music,” cautioned bands against the artistic and financial manipulations of major labels. It’s written in Albini’s caustic style: He likens an indie band’s pursuit of a major label sponsorship to clawing its way through a trench of “decaying shit” just to be the first to sign an exploitative, dead-end contract. For all its acidity, though, it was basically a bit of friendly advice to fellow artists about how not to fall into a trap that would ruin their pocketbooks and their band.

At other times, however, Albini’s provocations were simply obnoxiously juvenile if not downright vile. He casually tossed around racial epithets, homophobic terms, and references to violence and sexual assault. Later in life, he bluntly criticized and renounced his former “edgelord” schtick. But it took a while.

Albini’s provocative ways—but also his more humane and conscientious approach—had roots that went back to his time in Missoula.

Albini’s family moved to Missoula in 1973 so that his father, a pioneer in the mathematical modeling of wildfires, could work at the Missoula Fire Sciences Lab. Albini later described his father, Frank Albini, as the smartest person he ever knew. If you’ve ever read Young Men and Fire, you’ve come across Norman Maclean describing Frank as a “brilliant scientist.” And if you’ve ever worked in wildland fire and used a nomogram to help predict the behavior of menacing fire, you’ve used a tool that Frank invented.

But for teenaged Albini, Frank was a distant father. “He just sort of didn’t take us seriously as people when we were kids,” Albini said in a 2019 interview. “…I don’t really blame him. But I think that probably the way to make a kid happiest is to treat him like a person and take him seriously. That was a leap that my dad wasn’t able to make.” Struggling with insecurities and a feeling of lack of appreciation, Albini looked for attention elsewhere—or simply rejected the need for social approval. “I realized that as soon as I stopped giving a shit about what other people thought of me, all of those other problems would go away. … It’s an exhilarating freedom that you have when you don’t care if people like you or not.”

Albini’s nonconformity is evident early in his years at Hellgate High School. As a freshman in 1977, he fired off this brief letter to the school newspaper: “Death to the capitalist icon and the establishment insect! We have been ruled by the oppressive muctars long enough! The little people of the world shall rise and be TRIUMPHANT!”

Albini soon joined the school newspaper, the Lance, where he regularly courted controversy. He wrote a column titled “Papparazzo,” which he explained in his very first column was an Italian word for “a tiny bird that is very annoying.” The column fulfilled its destiny. But it was Albini’s music reviews that were the most divisive, particularly his disdainful reviews of two of the biggest arena rock acts of the time: Boston and Van Halen. Strident letters poured in, defending the honor of these groups (“Boston not boring!”) and calling for Albini to quit.

Halfway through his senior year, Albini’s provocations garnered him a full-page profile in the Missoulian with the headline, “Hellgate kids either love him or hate him.”

“I polarize people,” Albini said in the interview. “I’m kind of strange.”

Even after he graduated, Albini hate mail continued to flow in. The editor of Lance even asked him to write a guest column in late 1980, and Albini dutifully obliged with a column in which he ridiculed the Lance editor and then devoted the rest of column to the notion: “John Lennon is dead and I don’t really mind” (Lennon had recently been assassinated).

Albini’s controversial writing, however, was not always just rooted in a personal impulse to shake people up, to get them to understand that Boston sucks. In 1978, he wrote a long editorial denouncing homophobia and advocating gay rights. He followed that with a reported piece in 1979, “Growing Up Gay,” about the personal experiences of gay students at Hellgate. The story was devoid of the kind of prurience that sometimes characterized Albini’s writing. Albini detailed how homosexual students struggled with coming out, their diversity of sexual perspectives, the physical violence they endured, and the ways they found hope and community in their lives. The story concluded with a list of counselors, groups and other resources for gay students. Nothing like that had been printed in the Lance before, and nothing much like it would be again until the 1990s. Some adults considered the article inappropriate, Albini told the Missoulian. But he explained his impetus for writing it: “I had a friend who was gay who told me that growing up and realizing that you’re different is something that should be talked about more.”

Writing was Albini’s main creative outlet in high school. But he was involved in many activities. He participated in student government, where he honed a deep knowledge of parliamentary procedure and used it to torpedo bills and candidates he did not like. It drove the other student politicians so crazy that some mounted impeachment proceedings against him. His obsession with detail in student government rules seems to prefigure his later obsession with the details of analog recording and music industry contracts

Albini was also involved in the student literary magazine, speech and debate, drama, photography and art. If you only had his high school resume to go on, you’d be forgiven for thinking Albini was one of those kids who joins a bunch of clubs to pad their college application. But these all appear to have been things he was deeply passionate about.

Music eventually rose to the top of the heap of Albini’s interests alongside writing. Although he hated 1970s arena rock, he had fairly catholic taste in music. But he gravitated to punk music—bands like the Ramones, the Sex Pistols and the Clash. What Albini saw in punk’s aesthetics (the elevation of authenticity over proficiency, the challenge to art as beauty) and punk’s ethos (do it yourself and don’t do it for the money) would guide him for the rest of his life.

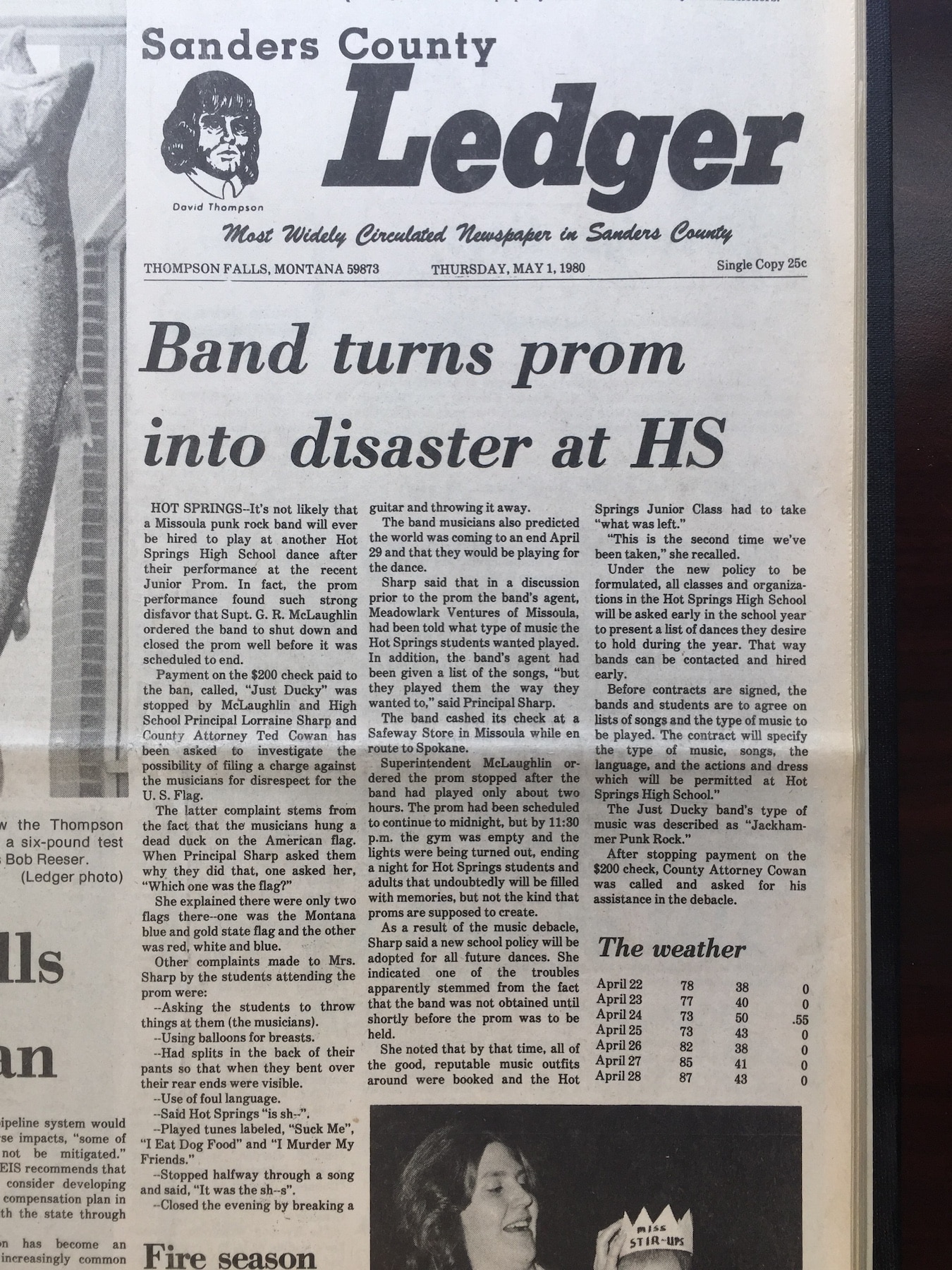

At the time, in the late 1970s, there was no punk music scene in Missoula. So Steve Albini set out to form one. He taught himself bass guitar and with several classmates formed Just Ducky in 1979. The band went through several lineup changes in its short career. But Just Ducky’s shows were even more chaotic. Albini and other members wrote songs about pubic lice and gave their songs inscrutable, unsavory titles like “Bugs in My Glove” and “I’m a Prick.” They tortured cover songs, smashed their instruments, and otherwise annoyed the audience, often successfully goading them to throw objects at the band. Reviews ran the gamut. Some found the shows entertaining, while others—written by fellow punks in the scene—found the shows pathetic: “All the punk anger of Andy Gibb,” Shawn Swagerty of the University of Montana’s paper, the Kaimin, quipped at the time. (Swagerty and Albini became friends in later years.)

Just Ducky played their most notorious show in April, 1980, when Hot Springs High School hired them to play the junior prom. It was a great victory for the band and a total disaster for the school. Among other things, students complained that the band used balloons for breasts, used foul language and “had splits in the back of their pants so that when they bent over their rear ends were visible.” The principal, meanwhile, looked into filing charges against them for disrespecting the flag after they hung a dead duck on the stars and bars. (Thanks to Dave Martens’ Lost Sounds project, two of Just Ducky’s original tunes have finally resurfaced on the compilation Without Warning: Early Montana Punk, Postpunk, New Wave + Hardcore, 1979-1991).

Just Ducky didn’t last long, but former members went on to form other early punk bands in Missoula, including Who Killed Society, the first band Albini recorded. By the early 1980s, Missoula had a small but active scene, with bands like Deranged Diction and Ein Heit. Some members of those bands would go on to form the more prominent grunge and indie bands Green River, Pearl Jam and Silkworm.

By the time the Missoula punk scene had coalesced in the early 1980s, Albini was in Chicago where he would live the rest of his life. He expressed little love for Montana, either while he was here or afterwards. But in an interview with the Missoula Independent in 2011, he credited his time in Missoula for a “pretty significant” part of his development. “The things about Missoula that are unique to Missoula are the sort of combination of Western libertarian mentality, the kind of live-and-let-live thing, which is tempered by a lefty-progressive element. … And I appreciated all that stuff and felt like, coming from Missoula, I had a fairly open mind.”

Despite leaving and rarely looking back (in fact, rarely even touring in Montana), Albini remained connected to the state in other ways. Arguably his most successful partnership as a recording engineer was with the band Silkworm, who, as they put it in a song once, also did their “time at Hellgate High.” (Albini described his time at Hellgate as a “brutal four years” in an “enema bag of society.”) Silkworm’s members were a few years younger than Albini and it was only after they, too, left Missoula for bigger cities (Seattle, then Chicago) that they connected with Albini.

In the 1990s, Silkworm at times seemed on the cusp of breaking out and grabbing a bigger audience, in the way that some similar bands like Pavement did. But it never happened. They did, however, garner a sizable and extremely dedicated indie fan base and produced a series of albums that ratcheted up good, and often rave, reviews in the music press.

Silkworm didn’t sound like Big Black or Shellac, but they had some affinities with Albini’s music and the type of music he often recorded: screeching, abrasive guitars; unconventional song structures; and, above all, an alternation of soft and loud vocals and music (something Albini had helped make a “thing” with his recordings of Slint and the Pixies).

Beyond aesthetic affinities, however, Albini and Silkworm just got along very well, perhaps in part due to their common, formative years in a similar place. It’s hard to know what effects Missoula may have had on shaping Albini and Silkworm, but they shared a fairly uncompromising ethos about the type of music they wanted to make. That was probably important in a philosophical sense, but also in a practical sense, in the studio, where Silkworm could make the music they wanted to and Albini could help them do it, which was the role he wanted. Between 1994 and 2004, Silkworm churned out eight records, all of them recorded by Steve Albini. No other band had a run like that with Albini. (Silkworm ended in 2005 when their drummer was killed in a car crash.)

Albini’s relationship with Silkworm exhibited his approach to music and art. Albini bent over backwards to help artists that he loved. Andy Cohen, from Silkworm, described Albini this way in an oral history one of my students conducted in 2019: “He went out of his way to give us discounts and find us deals with the studios and make it work with our budget. When we recorded records that sound like a million bucks, it only cost a few thousand. I feel like I’m forever indebted to him. … He wouldn’t think of it this way, I don’t think—that’s not how he thinks about stuff—[but] he probably contributed more to my musical career than anyone.”

Albini recorded some other important Montana bands as well, including avant-grunge greats Steel Pole Bathtub. And his generosity and helpfulness extended to smaller bands with links to Montana. Bill Badgley, from Federation X, recounted on social media recently how Albini changed what counted as a day for his “day rate” from 8 hours to 24 hours so the band could afford him. In addition to recording them, Albini cooked the tired rockers a meal (grass-fed Montana beef that Albini’s parents had sent him). When they still needed a little extra cash to cover their expenses, Albini suggested they quickly arrange to sell a song—which they did, eventually putting out a 7” with Missoula’s Wantage record label.

While Albini had rooted himself firmly in Chicago since 1980, he had clearly remained interested in the state and connected with people and issues there. More recently, he expressed admiration for Jeff Ament’s work funding skateparks in rural Montana. Ament, who grew up in Big Sandy, formed Missoula’s Deranged Diction in the early 1980s, then joined grunge pioneers Green River in the mid-1980s, before finally landing with Pearl Jam during the mainstream grunge explosion of the 1990s.

Unlike with Silkworm, Albini’s relationship with Ament’s bands was not friendly. Fresh off a show in Missoula in 1985, Green River traveled east for a couple gigs with Big Black. But Green River’s singer, Mark Arm, threw a fit after a blown fuse caused technical issues and Albini scolded him for his behavior. Albini also disparaged Pearl Jam as a band manufactured to capitalize on the grunge craze. But in 2021, when The New York Times wrote about Ament’s philanthropy, Albini posted: “I shit on Pearl Jam out of habit, but now I feel bad because this is absolutely fucking awesome. The isolation of rural Montana, particularly on the reservations, the stifling feeling of having no place to be yourself is immense. This is just fantastic.” (A few days ago, Ament wrote on Pearl Jam’s website: “Rest easy, Steve. You inspired a bunch of creative Montana kids to get out there and get in the mix in the early ’80s.)

Albini’s concern about Montana life has appeared in more material forms as well. In 2023, anti-trans members of the Montana legislature sought to bar Missoula representative and trans woman Zooey Zephyr from speaking. Activists protesting this at the statehouse were arrested. A bail fund was set up for them. The organizers noticed a relatively large donation and then saw the name of the donor: Steve Albini. Gwen Nicholson, one of the Missoula activists involved, recounted to The Pulp that, “We saw that Albini had donated, and we were like, ‘Man, the coolest people on earth are on our side. The dude who produced In Utero saw us and decided to lend a hand. We can do fucking anything.’ And of course, it wasn’t lost on us that Albini had done a lot for trans artists and was outspoken on trans issues. It was just part of who he was—he jumped in on things like that whether or not it was good PR or he caught flak. He had strong morals, and where do you find that in places like the recording industry?”

Albini was, obviously, a complicated person, like all of us. And, of course, he eschewed the distinction between celebrity and “all of us,” despite his unasked-for drift toward fame. He was abrasive and kind, judgmental and open-minded, rigidly principled but also willing to reflect and change. He went out of his way to provoke people, often with little consideration of the consequences. But he also went out of his way to help people, with little consideration of what it cost him or whether he would be credited for his generosity.

He was polarizing, but he was also polarized. He went to great lengths to show he didn’t care, and yet he cared deeply. He cared about Missoula—the crucible of his worldview—about Montana and the world; about music and art; about people. Steve Albini did give a shit.