In the late 1930s, the writer Norman Macleod returned to Missoula for the last time. Macleod had grown up in Missoula but left after high school. He became a prominent literary editor and poet, living in New York City and the southwest, among other areas. His return to Missoula to write a novel was something of a reckoning with his childhood, the place he grew up, and the time he grew up. The 1941 book that resulted, “The Bitter Roots,” is a coming-of-age story set in Missoula during the stormy and disorienting years of World War I.

The book has recently been re-issued by Boiler House Press’s Recovered Books, which aims to “bring forgotten and often difficult to find books back into print for a new generation to enjoy.” It is an enjoyable book in many respects — but don’t expect a Nicholas Sparks novel. As the Atlanta Constitution put it in a review in 1941, “The Bitter Roots” is not a “nice” story. Perhaps you gleaned that from the title!

Many reviews in 1941 noted the novel’s grimness, and it seems likely that the book’s sensibility and subject matter were unappealing to Americans who had just weathered the Great Depression and were on the brink of another Great War. The novel quickly fell into obscurity, even though Macleod continued to have a successful career.

“Nice,” however, is not the same as “good,” and it’s fortunate that Boiler House has reissued this book, which is enjoyable — even though it is not nice. It’s a forceful and fascinating story that explores masculinity from the perspective of a boy, at a time when masculinity was deeply bound up in war — both a military war abroad and a class war at home.

It’s a forceful and fascinating story that explores masculinity from the perspective of a boy, at a time when masculinity was deeply bound up in war — both a military war abroad and a class war at home.

As such, the book has a broader appeal than a regionalist portrait of a community in the American West. Nevertheless, readers of The Pulp will be intrigued by its depiction of Missoula from one hundred years ago. And they will not be disappointed if they read it. The novel is full of real places (some still here, some gone), real events (literally ripped from the headlines), and many only slightly fictionalized people.

“The Bitter Roots” follows Pauly Craig as he tries to make sense of the world in his first two years at Missoula High School from 1917 to 1919. The book opens with the United States joining World War I. Young men from Missoula volunteer or are drafted into the war effort. In that same year, laborers go on strike in a number of industries that are key to the war effort as well as central to Montana’s economy, in particular the lumber industry around Missoula and the copper industry around Butte. Both industries are dominated by the powerful Anaconda Mining Company. The war, politics and the strikes of this era are violent, divisive, and intriguing to Pauly — yet also mostly inscrutable.

Meanwhile, Pauly is trying to navigate social life in Missoula. His biological father is long dead. His mother is searching for a partner she hopes will be a father figure for Pauly. But the respected doctor she marries has no love for the boy he finds to be “different” and “unmanly.” The only real thing the doctor gives Pauly is use of the barn out behind their upscale house on Stephens Avenue. (The Queen Anne Style house, with a massive, curved bay window, is still visible at 410 Stephens Avenue). Pauly remakes the barn into a basketball court and clubhouse for his friends — or at least the people he hopes will be his friends.

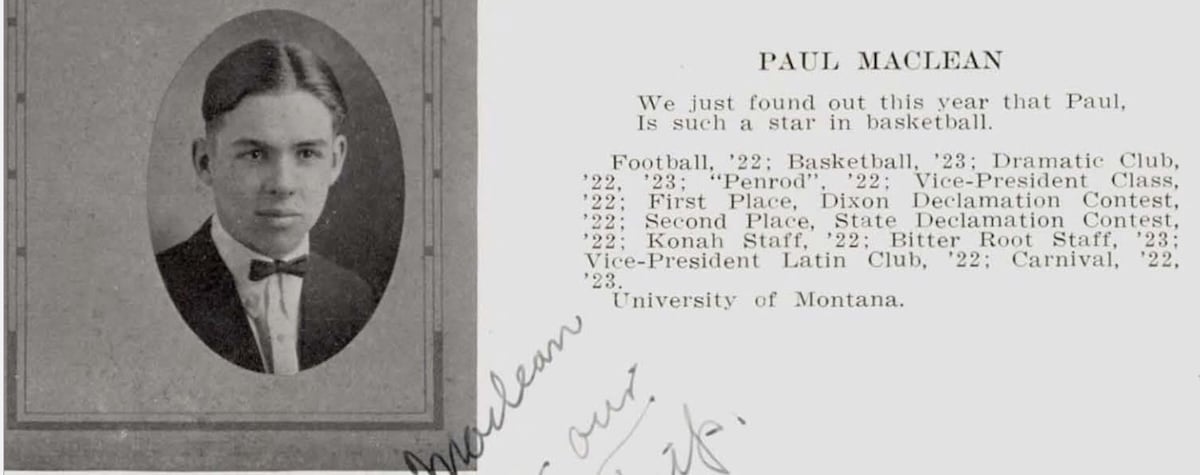

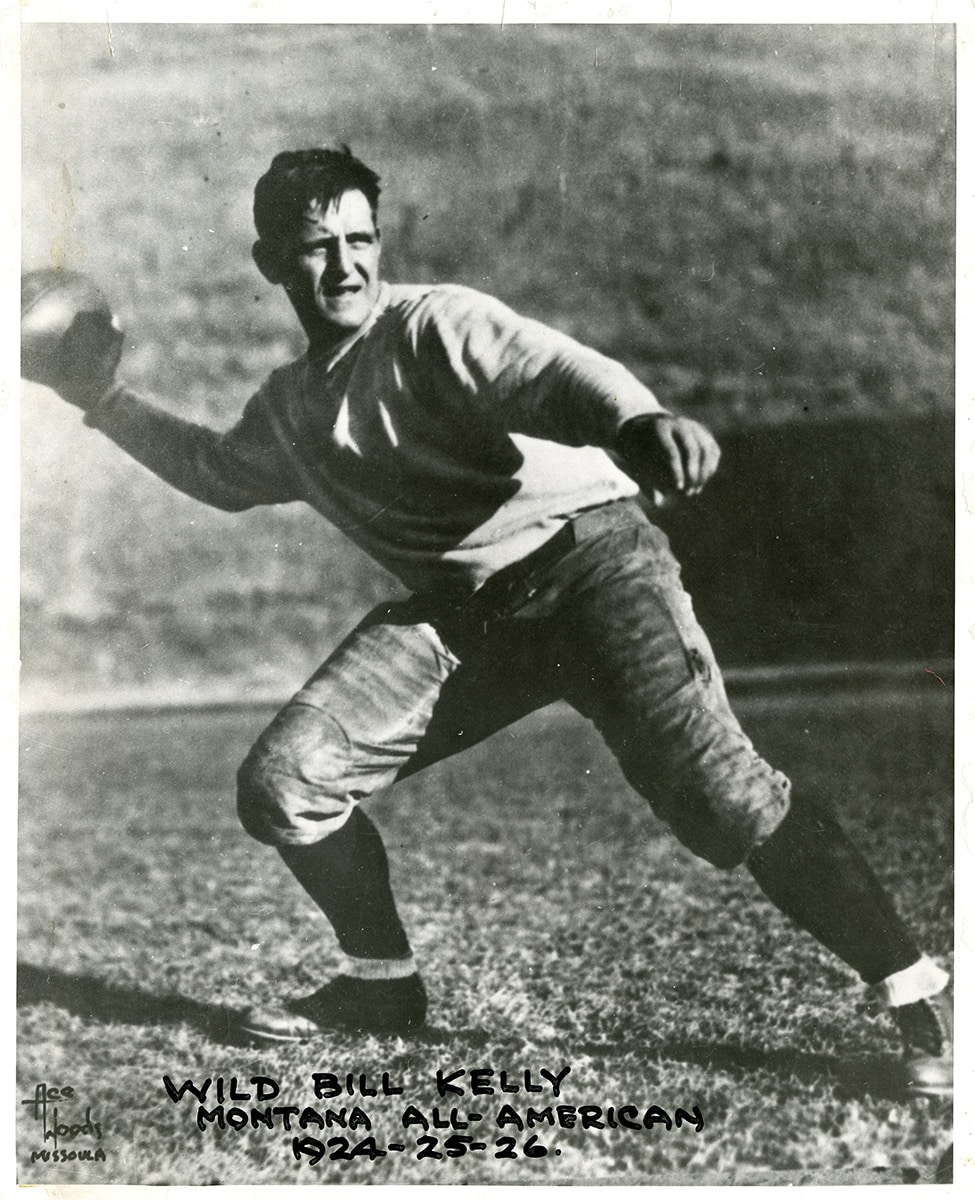

Throughout the book, Pauly (who is based on the author) runs around with a group of high schoolers from various walks of Missoula’s social life, most of whom are based on real people. For example, there is Betty Darling, the daughter of a prominent banker who Pauly has an unrequited crush on. Betty and her family are based on the Sterling family, whose father, Fred, was president of the First National Bank in Missoula. Another key character, Augie Storm is the son of a preacher. Augie is based on Paul Maclean, the son of Reverend John Maclean (minister at the First Presbyterian Church on 5th Street) and brother of famous novelist Norman Maclean. Brad Pitt plays Paul Maclean in the movie version of Maclean’s novel “A River Runs Through It.” Stiff Sullivan is based on a different local hero: William “Wild Bill” Kelly. The fictional Sullivan and real-life Kelly were both from working class families and both were local sports legends, particularly for their prowess on the football field. With these and other Missoula kids, Pauly plays sports, hops a train to Butte (there was an actual “Hobo club” at the high school at this time), and generally roams around Missoula doing youthful things.

References to these real places and cultural phenomena pop up every few pages in “The Bitter Roots,” giving Missoula history aficionados plenty to feast on.

Following Pauly and his associates as they roam around Missoula gives the reader a vivid, immersive sense of what the city was like in a way that no history book can. By the end, you can imagine yourself walking north over the Higgins Street bridge (now called Beartracks Bridge), glancing down at the large island underneath the bridge (now Caras Park) and the former north channel of the river that flowed hard against the buildings on the south side of Front Street. To your right, as you come up to Front Street, was the First National Bank, one of the cornerstone institutions of Missoula’s elite. To the left, down West Front Street was the red light district, the headquarters of the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and many ill-famed haunts. In “The Bitter Roots,” this included the unsubtly named Bucket of Blood bar. Missoula did once have an notorious establishment called the Bucket of Blood (on the north end of downtown), but it burned down in 1893. It’s likely, instead, that Macleod was inspired by Helena’s Bucket of Blood bar, which was perhaps the most notorious bar in Montana in the 1910s.

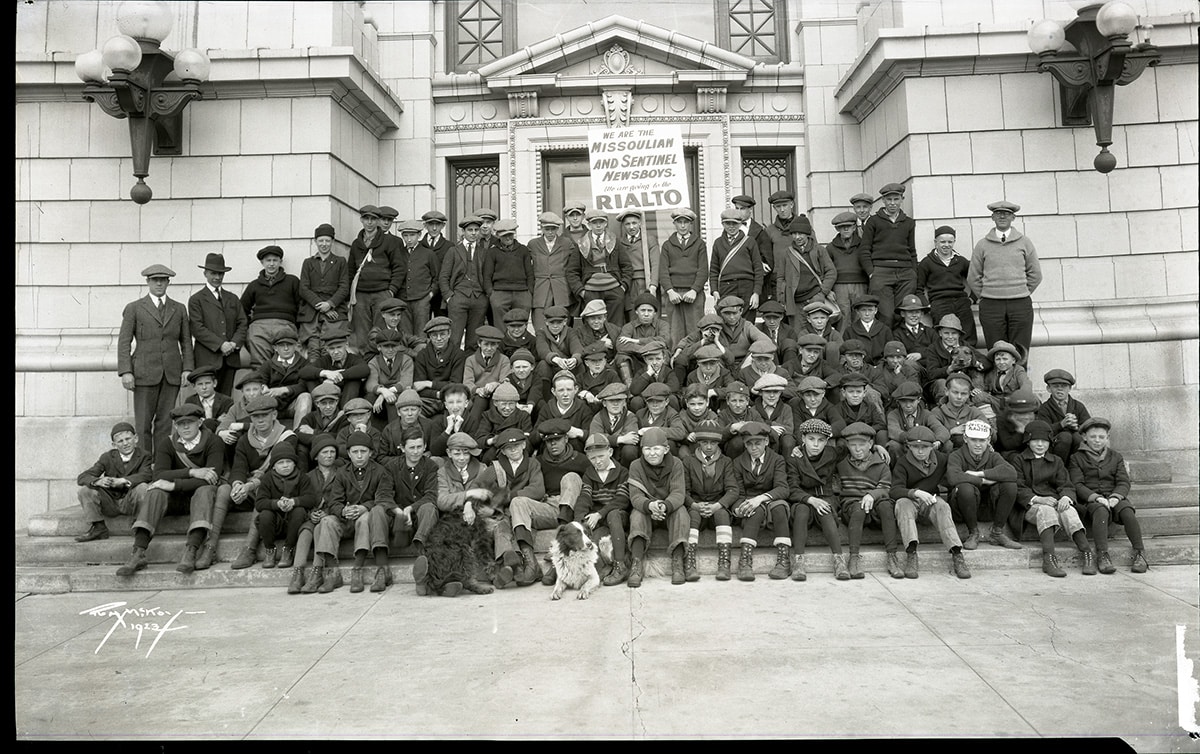

Walking half a block further north on Higgins you would come to the opening of Pig Alley. Down the alley was the back entrance of the Missoulian, where newsboys like Pauly picked up their papers to sell (and often got in fights with each other). It was also there that, during prohibition, you could slip in the back door of many former bars to surreptitiously drink a whisky. On the corner of the alley was Kelly’s Cigar store, located inside the Florence Hotel, where you could shoot pool or buy some cubeb cigarettes to smoke as an ersatz prop for looking cool, as Pauly and Lover do. Or, for some more wholesome fun, you could go around the block to get a banana split (a relatively new invention at that point) at the Palace Ice Cream Parlor on West Main. (It’s unclear to me if such a place existed, but there were a number of ice cream parlors in downtown Missoula at this time, particularly after prohibition.)

Blockbuster Hollywood feature films also exploded in this time period and along with them a host of movie theaters. So, like Pauly, you would have had lots of options for theaters and mind-blowing films. You could head to the corner of Higgins and Main where the Isis Theater might be showing a sensationalistic film about opium dens (probably the film Queen X, a silent crime-drama). Or you could head west on Main Street to the Bijou Theater (now the parking garage), where the juicy 1917 adaptation of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra might be playing, starring sex symbol Theda “The Vamp” Bara. Or you could walk a bit further north on Higgins to the Empress Theater (where Fact & Fiction is today), which could be screening The End of World, a sci-fi film about a comet hitting the earth (but also easily interpreted as a reference to the Great War).

References to these real places and cultural phenomena pop up every few pages in “The Bitter Roots,” giving Missoula history aficionados plenty to feast on. More diffusely, but no less interesting, are the broader social context and events. Macleod’s chapters begin with actual excerpts from newspapers: news about battles, parades, strikes, politics and so on. Macleod’s approach here feels a little heavy-handed, but the excerpts do give a sense of how a kid like Pauly might glean bits of the news. The excerpts also juxtapose the local, kid-centered world of Pauly against the broader world, as when one chapter begins with a news piece about a violent May Day riot in Cleveland, followed by a story of Pauly and other Missoula kids defending the “M.H.S.” letters on Mount Jumbo from vandalism by Butte kids.

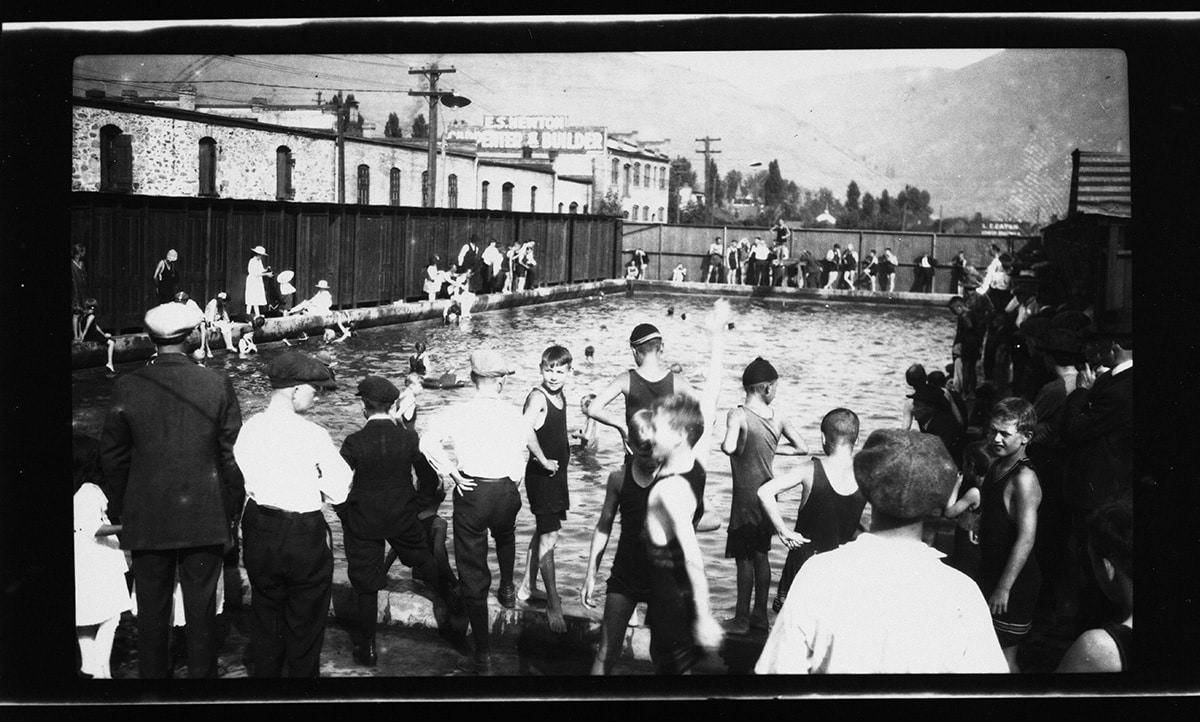

At the local level, one of the key issues that is threaded throughout the book — and is based on real concerns in Missoula at the time — was the epidemic of children drowning in the river and irrigation ditches. In the novel as in real life, Missoula residents banded together to fund a public swimming pool. The novel ends in 1919, before a pool is built. But in 1920, Missoula did actually build a public pool.

The novel opens with a drowning that catalyzes the city to action around the pool. But more fundamentally, the events surrounding the drowning set up the key dynamic that the book is concerned with, namely Pauly’s confrontation with masculine identity, ideals, and violence.

The initial scene will be familiar to many kids who grew up in Missoula: On a hot summer day, Pauly gets on his bike, weaves through his residential neighborhood, and arrives at the Van Buren bridge to swim. As it does today, the bridge spanned the Clark Fork River, the irrigation channel to the south, and the land in between (what we now call Jacobs Island). There, on the island, kids jump in the water, cool off, joke around, and have fun.

But the nostalgic glow of this setting quickly darkens. Pauly changes into his swim trunks. But before he can get into the water he catches the attention of Augie, who teases him: “What’s the trunks for, sonny?” Pauly says he just wants to swim. Another boy, Loney, tells the other kids to take Pauly’s trunks off, saying: “Let’s see if he’s a man yet!” The other boys wrestle Pauly down, remove his trunks, and toss them in a tree. Pauly is humiliated, and slips into the water to cover himself.

Things get worse. Augie and the other boys turn their attention to a slightly younger boy called “Honey Pie,” asking him if he can swim across the river. Then Stiff Sullivan tackles Honey Pie, and Augie and the other boys heave Honey Pie into the surging main channel of the Clark Fork. Belatedly, the boys realize that Honey Pie cannot swim at all. The young boy disappears under the current. Augie dives in to look for him, but he is gone.

The role of Augie and the other boys in Honey Pie’s death never comes to the attention of the broader community, who see his death as just another accidental drowning. And it is after this that the town decides to build a municipal swimming pool.

Like no other book I’ve read, “The Bitter Roots” is an unblinking look at the pervasive, grinding nature of male aggression in boyhood.

In real life, Paul Maclean, who Augie is based on, was not involved in such an incident as far as we know. In fact, Maclean became a lifeguard at the Missoula municipal pool in the 1920s and in that capacity saved one boy from drowning. But for “The Bitter Roots,” this episode is just the dramatic opening salvo for a story of boyhood where the threat of male aggression and violence permeates every interaction.

If you are a male, this threat will be as familiar to you as swimming in the river is to a Missoula kid. When you walk into a situation with other males who are strangers, or at least not your friends, it’s entirely possible that someone will physically assault you. The pretext could be any number of things, and often is quite arbitrary. It’s not usually about you, personally. The initiator is trying to play out a masculine script, and has simply conscripted you into his imagined movie. Perhaps you can avoid it, perhaps not. Probably nothing will happen, and if it does, it will probably not cause serious bodily injury. But you always know in the back of your mind that these are possibilities. It takes little more than an off-hand comment, a hard stare, or an accidental shoulder bump to foreground the possibility of violence. Like no other book I’ve read, “The Bitter Roots” is an unblinking look at the pervasive, grinding nature of male aggression in boyhood.

Pauly tries to survive in this world but also understand it, particularly through Augie and Stiff. They are both tough and athletic, but their masculinity is connected to broader cultural currents — particularly war and class conflict — in different ways.

Stiff Sullivan, working class and raised on Missoula’s northside, has roots in Butte, where his miner relatives are associated with the IWW. While the union didn’t formally oppose the war, members like Frank Little — lynched in Butte in 1917 — did. Like Little, Stiff comes to see the war as a capitalist slaughter, driven by profit and paid for with working-class lives.

Meanwhile, Augie grows increasingly jingoistic, showing contempt for war opponents and those he sees as obstructing the war, such as the IWW. As Stiff is sobered by the war and class conflict, drifting from juvenile antics, Augie is propelled the other way—toward violence, delinquency, and nastiness.

Though largely based on Paul Maclean, Augie may also draw from others Macleod knew such as his peer John K. Hutchens. Like Macleod, Hutchens rose in the literary world as a writer and editor, but held very different political views. John was the son of Martin Hutchens, a Chicago editor who moved to Missoula to lead the Missoulian after the Anaconda Company took it over in 1917. Though Anaconda opposed the IWW, Macleod later noted Martin’s paper treated the group fairly. John, however, was harsher, writing in his 1964 memoir that Missoula’s IWW were “murderers and thieves.” Whether or not Augie was a composite of Paul Maclean and John Hutchens, he embodied the intense hatred some held for the IWW.

But part of what is so interesting about “The Bitter Roots” is that it shows how much more variegated were the connections between masculinity and politics a this time. Augie displays his masculinity through his belligerent support of the war and against labor agitators who threaten it. But his masculinity is hardly the only acceptable kind at this time, and in many ways his warmongering seems compensatory. Meanwhile, Stiff — anti-war, leftist radical — seems comfortable in his masculinity and remains an uncontroversial local hero due to his athletic prowess.

Over the course of the twentieth century, masculinity has become much more polarized. Shaped by a variety of factors, including Cold War anti-communism and deindustrialization, masculinity has become increasingly associated with individualism, conservatism and reactionary politics. Meanwhile, leftist and anti-war politics have become associated with weakness and are portrayed and seen by many Americans as unmasculine.

“The Bitter Roots” is a snapshot of time that is both familiar and foreign. It’s not a romanticization or vilification of a time and place. Nor is it an explication of Macleod’s ideas about masculinity or war or class conflict. It’s a novel. It’s complicated. There are no satisfying explanations or resolutions. But if Macleod’s focus on the pervasive, suffocating nature of masculinity can feel merciless, it is also compelling. No, “The Bitter Roots” is not a nice novel. But it is a powerful one. Jump in. The water is not fine.