Linds Sanders paints cats and dogs.

And chickens.

And—if you have one—a lizard, snake, horse, hamster, parakeet, or potbellied pig.

Sanders is a professional pet portraitist.

She’s also a counselor at Tamarack Grief Resource Center.

Now she’s combining both roles in preparation for an art exhibition of memorial pet portraits at the Headwaters Foundation in downtown Missoula.

“This project honors animals who have lived in Missoula, who’ve been Missoulians, who have swam in the Clark Fork, who have looked out the window at passerbyers, who’ve hiked the M, who’ve eaten Missoula bugs and breathed Missoula air and basked in Missoula sun,” Sanders says.

“I want the show to be an overwhelming picture of love and awareness that these are animals who lived, who meant something, who were Missoulians in their own right, and who are deeply missed.”

‘Griditude’

Sanders, 33, is from Billings, but moved to Missoula to attend the University of Montana, where she majored in journalism and “took every art class I could.”

Her senior year, she had a solo show at the ZACC called “Griditude”—a portmanteau of “gratitude” and “grid.”

All the pieces were portraits of people who’d loved and supported her, including her parents, close friends, her high school art teacher, and her art mentor at UM.

Each piece was based on a single photo, using a grid to perfect the proportions.

The same technique still underlies how she paints today.

“Portraiture for me really requires a good-quality photo,” Sanders says. “I have to stick with it, scale it back, and capture a single look or a moment—like a dog when they’re ready for a W-A-L-K, or a cat when they’re sleeping.”

She came to her pet portrait speciality during the Covid-19 pandemic, when she and her husband, photographer Brian Christianson, spent two years traveling the country in a used black Ram ProMaster cargo van they rebuilt as an RV.

“Doing art in the van was really hard,” Sanders says. “There was one small surface—maybe two feet by a foot and a half.”

One winter, a friend let them crash in her uninsulated beach house on the Delaware coast.

“We went and bundled up and there was a kitchen table and that was such a gift,” Sanders says. “I just painted for days at that kitchen table.”

Offering portraits of people’s pets became her way to treat friends and thank everyone who hosted her and Christianson.

In 2022, the couple circled back to Missoula, where Sanders entered the graduate program in counseling at UM—and started taking paid pet portrait commissions.

“To this day, I paint at my kitchen table,” she says. “I’m just so grateful for tables.”

Whiskers to wattle

For hundreds of years, royals and nobles have commissioned paintings of their animal companions.

Pet portraits for the rest of us is a much more recent popular phenomenon, fueled by the pandemic pet boom, expanding definitions of family, and social media and celebrity trends.

By one report, in the 10 months between March 2020 and January 2021, nearly half of Americans got a new dog, one third got a new cat, and one in seven got both a dog and a cat.

Isolation increased intimacy—and drove more people to connect and share about their pets online.

Last December, when Time magazine chose Taylor Swift as the 2023 Person of the Year, the most celebrated of multiple cover photographs was the singer with her cat.

Now pet portrait painter and pet portrait photographer have become actual occupations—or at least side hustles—for Sanders and other Missoula artists like Kara McGrane, Kim West, Rachele Barker, and Stella Nall.

Sanders takes orders via a one-page form on her website.

For $115, you send her a photo of your animal and she paints a 5×7-inch wood-paneled portrait. Shipping, if necessary, is an additional $10.

But there’s a 10 percent discount if you’re the first person to commission a portrait of a particular species.

Sanders, whose personal tattoos include a fox, cormorant, turtle, whale, birds, bees, and jellyfish, grins.

“I would love to paint a horny toad,” she says.

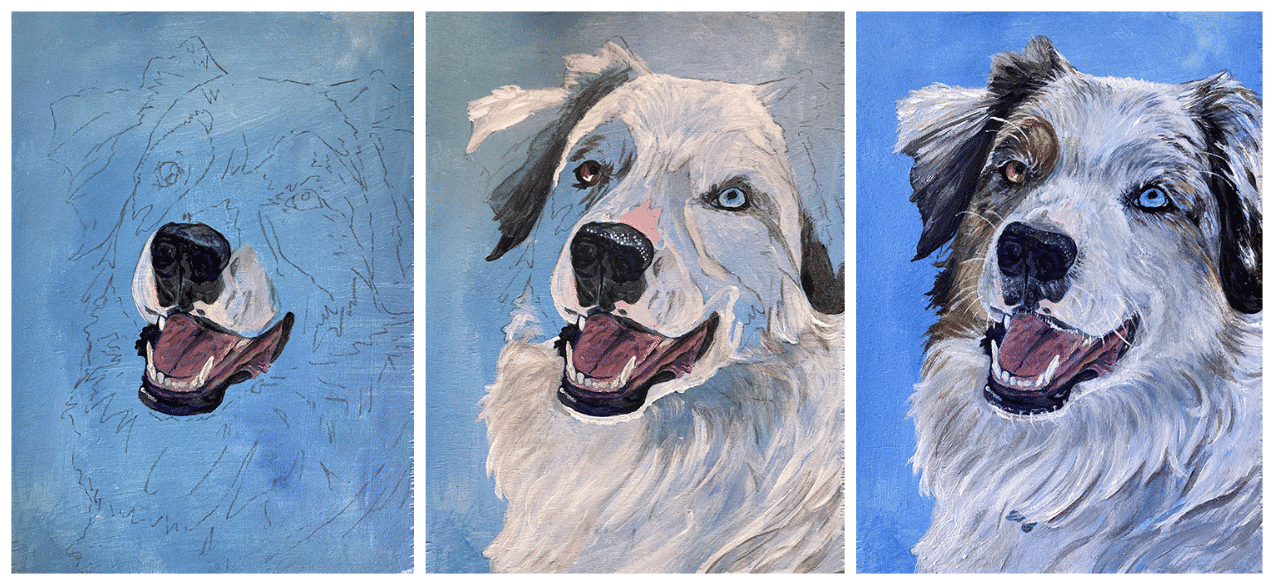

Whatever the animal, each portrait takes three to four hours from start to finish, a process the artist often documents via time-lapse videos.

“It’s so weird to watch because I’m bouncing all over the place, it’s not super methodical, but it always comes together in the last 10 percent,” she says.

“Uh-uh” turns to “wow” when whiskers, catchlight in the eyes, the wetness of the nose, or other intimate details enter the picture.

On her first commissioned chicken portrait, for example, Sanders knew she’d nailed it when she got to the wrinkles on the bird’s red comb and wattle.

“When I gave it to to the owner, he said, ‘Oh, you even got the part where she got frostbit one winter!’”

An everyday appreciation

Seemingly everyone in Missoula has and loves a pet.

“They’re unique connections,” Sanders says. ”We are caretakers, but also I think a lot of people would argue that our pets take care of us, too.”

At the same time, as she’s witnessed, most of us struggle knowing what to say or feel when beloved non-human family members die.

“As a grief counselor, I’ve seen how deeply people are impacted by pet loss, but how this is often experienced as disenfranchised grief, in which society doesn’t recognize/honor/accept the loss as readily,” Sanders says.

(Other examples she gives of “disenfranchised grief” are deaths by suicide, accidental overdose, or Covid if the person wasn’t vaccinated.)

Even with all the Tamarack Grief Center offers, someone mourning a pet may feel isolated or uncomfortable, Sanders observes.

“It’s very brave and I really admire the people who are like, ‘No, this is grief, I’m going to come to a grief center,’ but that takes a lot of awareness and acknowledgement.”

Hence the concept and pitch for her show of memorial pet portraits.

It will take place this October, timed to coincide with the annual Missoula Festival of the Dead, but she’s putting the word out now in order to solicit as many subjects as possible.

“I want there to be a collective grieving,” Sanders says. “And I think even if someone’s looking at a portrait of an animal that’s not their own, there’s a reminder of the animals that they’ve been honored to caretake. So my idea and dream is Missoulians who are grieving animals or who are anticipating grieving an animal being willing to be part of the project of their animal being painted and then being in this collection of paintings.”

Work toward that end comes one commission at a time.

“I feel honored to be invited into people’s homes and lives and that really special relationship,” Sanders says.

At her own home, she and Christianson care for a white-pawed tabby cat, Roo—short for kangaroo—who mews conversationally and sits on Sanders’s lap as she paints.

Roo is only two years old.

Still, in the back of their minds, Sanders says, the couple is already grieving the fact that death will someday separate Roo from them.

”It’s not really a sad grief,“ she clarifies. ”It’s more, ‘Wow’—just an everyday appreciation.”

“She’s the cat of a lifetime,” Sanders says.

Linds Sanders’ website, with more information about commissioning a pet portrait or participating in her upcoming art exhibition of memorial pet portraits.