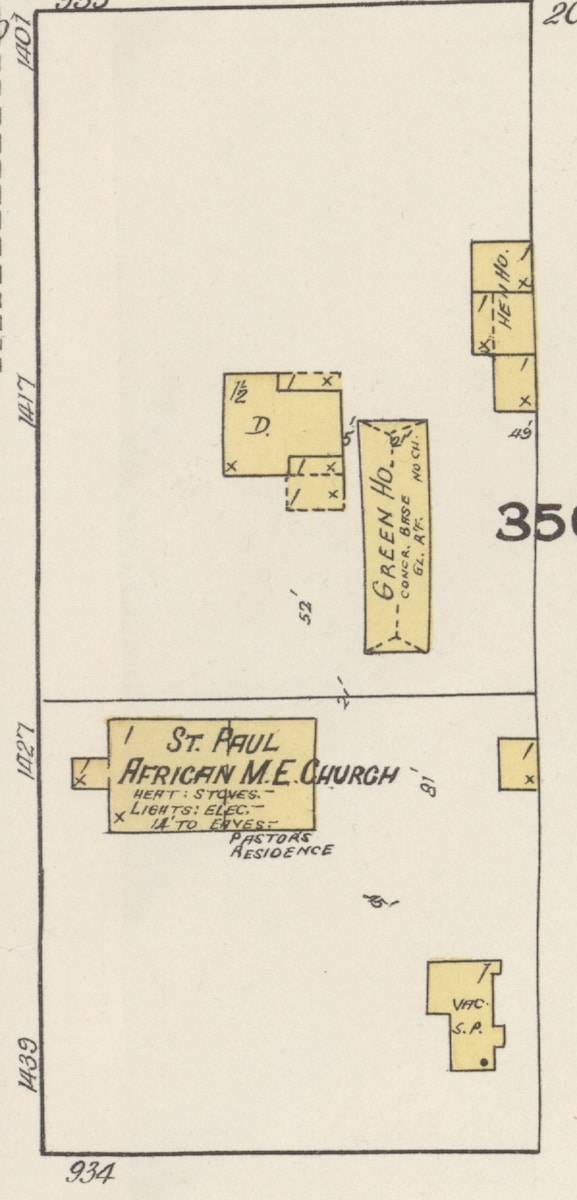

The old Lowell school building had to be moved within 10 days of being sold. That was the condition the school district gave to Missoula’s newly formed Black church when they sold it to them for $200 in April of 1910. It wasn’t going far. The trustees of the church had purchased two lots nearby on the 1400 block of Phillips Street in the burgeoning Westside neighborhood where the church was going to be located.

But the building had hardly moved before a firestorm in the Westside community took hold. The impetus of the dust-up came when a neighbor, James Ryan, refused to allow the movers to traverse his property to reach their destination.

Because the cost of taking an alternate route was more than they were being paid, the movers abandoned the job and left the building straddling Ryan’s lot and its original location. White Westside residents took the opportunity to not only attempt to stop the Black church from moving in, but to prevent Black people from living in the area at all.

“‘To take all lawful ways and means at our command to prevent the colonization of the west side by negroes.’ This was the sentiment of a meeting held at the (new) Lowell school for the purpose of discussing the negro question on the west side,” reported the Missoulian on April 22, 1910.

In this meeting of aggrieved Westsiders, neighbors attempted to pressure members of St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) to sell the building to them and forego their plans of having a church in the neighborhood. Trustees of the church—three of whom were former Buffalo Soldiers stationed at Fort Missoula—almost gave in to the pressure, but after speaking with regional AME leadership in Spokane, they refused. White residents were so worked up that they also decided to form a committee to pressure real estate agents and landlords in the area not to rent or sell property to Black people in the neighborhood.

That the Missoula area had an active Black church and a significant Black population in its early history may not be well known today as visible signs of their presence are rare and few local Missoula historical exhibits make much reference to it.

Just four days later, a letter to the editor signed by “A Colored Citizen” appeared in the paper.

“As a colored citizen of the west side, I would like to ask the white citizens there to explain their reasons for protesting against the colored Methodist church being located in that locality,” they wrote. “We would also like to know why the colored people of the west side have been called ‘undesirable citizens.’ What have we done that this should be said of us?”

A lengthy response quickly appeared in the paper a few days later, titled “A Colored Citizen’ Receives An Answer.” Signed by “A Property Owner And West Side Resident,” the letter gave a thorough list of grievances exposing profound levels of racial resentment.

“A colored population, be it good, bad or indifferent, is never a desirable population in a white community. Natural, social and civil law forbids the mixing of the white and black races,” they wrote. “The citizens of the west side bought property and improved it, built themselves comfortable homes. The establishment of a negro church in their midst and the consequent drifting in of a colored population and locating around the church will depreciate property values and necessitate removal of all white people who do not desire to live in a negro community.”

Just two weeks later, the 4th Ward Improvement Club (an organized civic group of Westside residents) met to formally reaffirm the neighborhood’s commitment to boycotting landlords and real estate agents selling or renting to Black folk. To underscore their fears, “a prominent business man” shared a likely embellished story during the meeting.

“I saw an incident the other day which shows the tendency of the negro. While doing some work around the house I heard a screaming and turning around saw two colored boys, from 9 to 12 years of age, grab two little white girls about 8 years old, and kiss them. I shouted and they ran away. This shows just what we must expect if the influx of the negro into our midst is not checked,” he wrote. “(I)f matters go on in this manner, it will not be safe for our wives and daughters to move out of the house after dark.”

It was an inauspicious beginning for St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church. Yet despite the vehemently racist response, the church was able to establish itself on the Phillips Street location, holding services and serving as a bulwark for Missoula’s early Black population for nearly three decades. Even after it shut down in 1938, the minister of the church, Webster Williams, continued to live at the residence until his death in 1944. In 1946, the church building and lot were sold to a private resident. Eventually, it was renovated and remodeled into a private home and any visible signs of what had been Missoula’s only Black church vanished.

That the Missoula area had an active Black church and a significant Black population in its early history may not be well known today as visible signs of their presence are rare and few local Missoula historical exhibits make much reference to it.

This is a pervasive problem across the country.

Of the 95,000 sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places, only 3 percent focus on the experiences of Black Americans. There are several reasons for this. Eligible listings, for one thing, have to have “architectural significance” which often precludes buildings tied to Black history such as slave cabins or tenement buildings that have fallen into disrepair. Also, the nature of urban renewal programs and the building of highways have disproportionately demolished historic Black neighborhoods.

Another factor working against Black historical preservation is the fact that sites of significance are overlooked or forgotten because the greater white community did not value their presence or significance at the time.

Such was the problem in commemorating St Paul AME Church. The church’s demise was rarely, if ever, referenced or noticed by Missoula residents for many years. By the time its history was given more attention, the property had either been demolished or renovated beyond the point where it would be eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. No known photos exist of the building when it was the church or of the members who maintained it.

And yet its significance is difficult to overstate. There, at 1427 Phillips Street, a burgeoning Black population in 1910 poured its aspirations for belonging. The property represented more than just a place for spiritual fulfillment—it was a place to gather and organize. At a time when Black people were being systematically denied the basic rights and freedom of citizenship in the South—when lynchings were a daily occurrence, when voting rights and political representation was stripped from them and Jim Crow segregation rendered them second-class citizens—a Black community in Missoula was expressing a desire to live here through the establishment of St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Recognizing this, the Montana Historical Society recently approved and funded the creation of an historical sign memorializing the church. And this past October, with support from the Missoula Black Collective, the city installed the sign on the boulevard in front of the lot where the church once stood.

“MTHS very rarely manufactures signage for places that are ineligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places,” said Montana Historical Society Interpretative Historian Christine Brown, who took the lead in drafting the wording and appearance of the sign. “However, we believed it was important to create this sign for the Missoula AME church to raise awareness of Missoula’s historic Black community.”

During a special ceremony held at Heritage Hall on the Fort Missoula campus on May 24th, Missoula’s Historic Preservation Department honored the sign’s placement with an “Excellence in Historical Interpretation Award,” a new category for the annual awards. Historic Preservation Officer Elizabeth Johnson nominated it, recognizing that there is more to historical preservation than commemorating histories that are still visible.

Visibility is a key element to this problem. Considering the state of Montana as a whole is currently the least Black state in the country (in terms of percentage) and Missoula, while above the state average, is under 1 percent Black, it becomes easy to believe Black people do not have a history here.

But don’t be fooled.

While Missoula County’s Black population in 1870 and 1880 was negligible, the arrival of the segregated 25th Infantry (popularly known as Buffalo Soldiers) in 1888 changed that dramatically. For 10 years, from 1888 to 1898, anywhere from 200 to 250 Black soldiers called Missoula home. And just a few years later, the other segregated Army infantry regiment, the 24th Infantry, posted a battalion of soldiers as well. That’s 13 years between 1888 and 1905 where close to 2 percent of Missoula’s population was Black.

And as soldiers at Fort Missoula, the men played an outsized role in the community relative to their numbers. Fort Missoula soldiers were key participants at major community gatherings—from leading Memorial Day commemorations, to marching in the front of the line at 4th of July parades. The 25th Infantry Band played for crowds regularly. They were part of the festivities for the grand opening of the Florence Hotel in 1888 and they were there at the funeral of Missoula co-founder Captain Christopher P. Higgins in 1889. When Captain Higgins’ son and former Missoula mayor Frank Higgins died unexpectedly in 1905, Black soldiers from the 24th Infantry were present at his funeral as well.

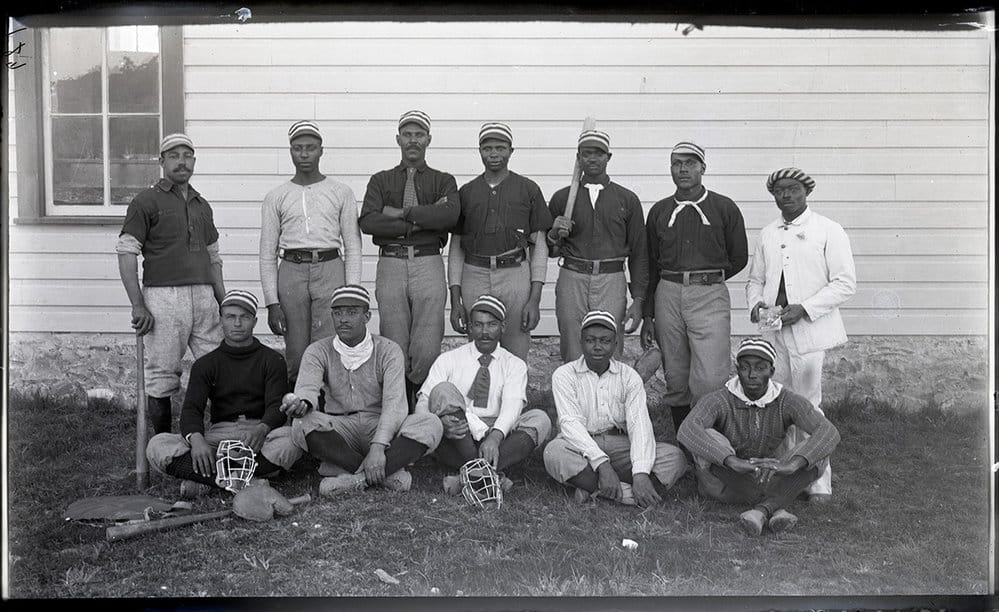

Fort Missoula’s Buffalo Soldiers fielded baseball teams that played local teams throughout the area, in Missoula, Bonner, Frenchtown, Stevensville and Hamilton. As one of the most cherished local leisure activities at the time, these games drew large crowds where the soldiers became a regular staple of weekend activities. One former soldier and baseball player, Samuel Freeman, even came back to live in Missoula and fielded an all-Black baseball team called The McIntosh Reds in 1908.

It’s a confoundingly obscure fact that, at a time when 90 percent of the Black population in the U.S. lived in the South, Missoula had such a noticeable Black presence.

And it was this foundation laid by their time here that saw the area’s Black population more than double in size. By 1910, between 0.80 percent and 1 percent of the town’s population was Black. While that may seem rather small, it’s a significantly higher proportion than San Francisco County or Portland’s Multnomah County at the time.

There is a straight line from Black soldiers at Fort Missoula to the creation of St. Paul AME church and the growth of Missoula’s Black population. In 1910, close to half of all Black children living in Missoula County had Buffalo Soldiers for parents. And on the deed of purchase of the property on Phillips Street by the AME church, three of the five trustees named were former Buffalo Soldiers: Chester McNorton, Alexander Pillow and Raleigh C. Bibbs.

St. Paul served as a gathering place for Missoula’s Black residents, providing them a much-needed institution for surviving in an openly racist climate.

On the face of it, the church purchase made a lot of sense. The building and lot were on Missoula’s Westside, a working class neighborhood where several Black families had begun to settle. On top of that, the community had seemingly warm regards for the 24th and 25th infantries during their time in Missoula. When the 25th Infantry left in 1898 to fight in the Spanish-American War, the town came out in droves to bid them farewell. And when the 24th Infantry left Missoula in 1905, a Missoulian editorial noted, “The city will regret to lose the members of the 24th … Missoula has had much experience with soldiers, white and colored, and prefers the latter.”

They did not, however, seem to prefer them as actual neighbors as the fracas surrounding the church purchase in 1910 demonstrates. Yet for the next 28 years, St. Paul served as a gathering place for Missoula’s Black residents, providing them a much-needed institution for surviving in an openly racist climate. They held regular services but also special events both for themselves and the greater community. St Paul’s women’s group, the Martha Washington Club, was probably the first group to ever acknowledge the growing “Negro History Week” in Missoula when they held a special gathering for the occasion at the church in February of 1930 and invited anyone to attend.

Interaction with the community was essential and the church reached out regularly. They hosted annual Southern Barbeques in Greenough Park, inviting the community and drawing large crowds. They put on jubilee choir performances at the church for both Black and white audiences to hear members sing traditional Black spirituals. The Martha Washington Club held other events aimed at reversing pervasive anti-Black stereotypes that flooded America in that time, including holding a Frederick Douglass and a separate Lincoln memorial.

The constant outreach likely helped get community support in 1923 for a year-long fundraising campaign for the church with support from the Kiwanis Club and Elks Club. But the publicity for that effort also drew the attention of Missoula’s rapidly growing Ku Klux Klan, whose members, hooded and dressed in full KKK clothing, interrupted the church’s service in late July, marching down the aisle and facing the crowd in a semicircle. The purpose behind the Klan’s dramatically terrifying intrusion was to donate $20 to the fundraising effort. They did it again in 1926. Klan history in Missoula is another overlooked part of our town’s past—but it wasn’t unique to Missoula. The KKK nearly became a mainstream organization in the 1920s with chapters from state to state and developed its largest total number of members in its history. Fortunately, Missoula’s surge in Klan activity and membership collapsed quickly and its presence was all but gone by the end of the decade.

Missoula’s St. Paul AME church outlived the Klan and continued holding services and special events until 1938. But the upheaval of the Great Depression and World War II unearthed the tenuous foundation Missoula’s Black community clung to in the early 20th Century. With the national unions from the two major industries in Missoula systematically barring Black people from membership, no Black person in Missoula was able to work in the lumber mills or for the railroad. They were consigned to the lowest-rung of the occupational ladder, with the bulk of the population only able to get jobs as porters, shoe-shiners, servants, laundry workers or janitors.

The front line of job losses from the Great Depression was the service industry, decimating that sector of the labor market and impacting Black workers more intensely than white. As the decade continued and industrial manufacturing in coastal cities grew, Missoula’s early Black population left in large numbers for Portland, Seattle, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

They were also facing an uphill battle with the racist legislation banning interracial marriage enacted in 1909. This hit states with smaller populations disproportionately. In a mid-size town like Missoula that had the seed of potential to maintain a Black population, the law dramatically reduced the options for young Black residents to build a family and plant roots here.

From 1940 to 1960, Missoula’s Black population dropped rapidly while the town simultaneously grew significantly. The opposing movement of demographics underscores and highlights the differences in opportunities for Missoula’s Black and white residents. In 1910, there were 162 Black people living in Missoula County. By 1960, that number dropped to 54. Yet Missoula had nearly doubled in size during that time.

In an article published by The New Yorker in 2020 about the struggles for including Black history in the National Registry of Historic Places, writer Casey Cep offered a poignant insight from Brent Leggs, the director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund at the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In discussing the fights around preserving Confederate monuments, Leggs noted that that struggle got a vastly disproportionate amount of attention over the efforts to highlight and preserve Black historical spaces.

“(T)hat debate has only reinforced what Leggs has believed for decades: that preservation is political, and that the kinds of places and structures that we protect are less an indication of what we valued in the past than a matter of what we venerate today.”

It seems fairly obvious that for a variety of reasons, Missoula residents failed to venerate the significance of Missoula’s Black church and the modest but significant Black population the community had at the time. Our cultural memory was shaped by that reality. Re-inserting this history and valuing it may raise uncomfortable questions for white Missoulians now: Why wasn’t this history preserved earlier? If Missoula had a significant Black population in 1910 with an active AME Church, why didn’t they stay?

But at the same time, an historical marker honoring this history in town now is a clear reminder that Black people do have a history in Missoula and that the questions of race that bedevil us to this day are as relevant here as anywhere else in the country.