Visitors to Caras Park in downtown Missoula can now descend to the Clark Fork River via elegant ADA-accessible ramps and sand-colored stone steps, part of a $1.6 million riverbank improvement project completed this spring. An expanded viewing platform offers a prime panorama, and terraced seating below gives the revamped riverfront the feel of an amphitheater. The stage, then, would be Brennan’s Wave, Montana’s only engineered surf wave, where kayakers and surfers are always putting on a show. Brennan’s Wave, certainly, fortifies the collective, river-loving heart of Missoula.

But beneath these shiny surface improvements lies a more complicated reality: The wave that serves as the centerpiece of this revitalized park space — and downtown itself — is broken and could fail completely without the repairs that no one entity seems willing or able to fund.

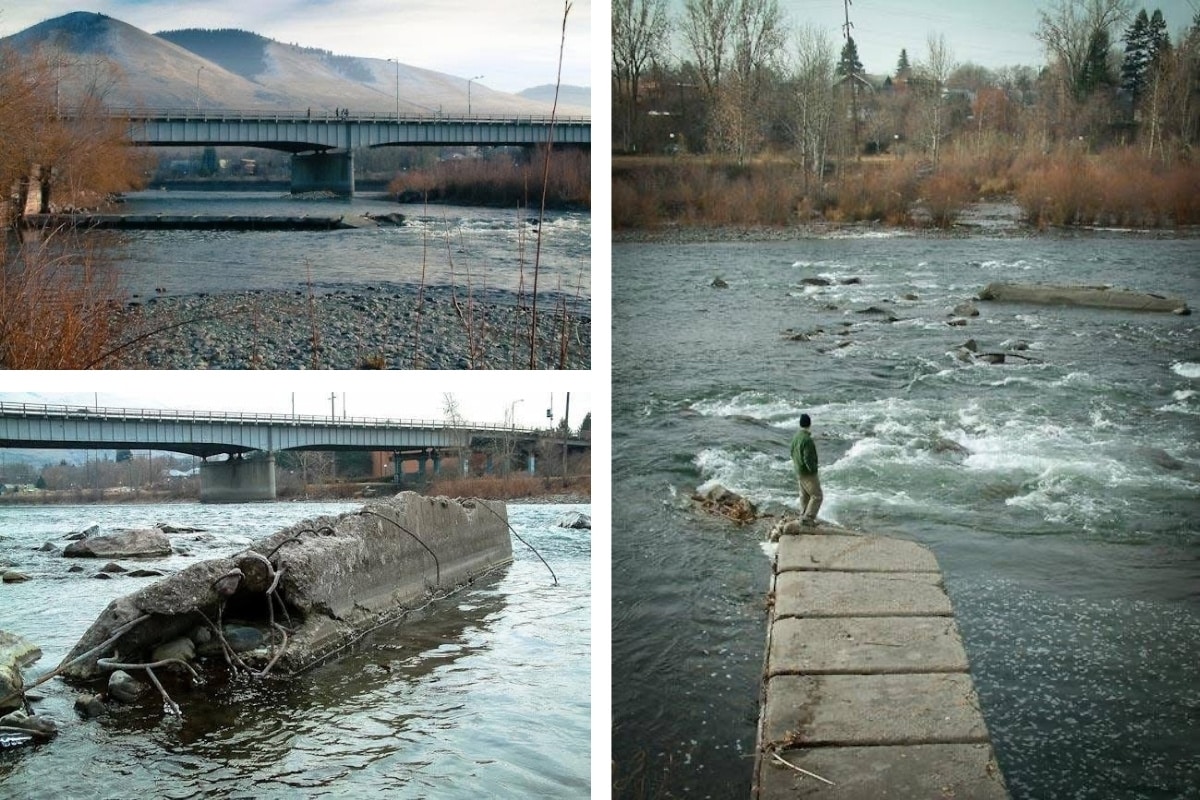

Brennan’s Wave, built in 2006 to replace a dangerous irrigation diversion, has been damaged since a 2011 flood event knocked boulders loose from its structure. The wave continues to function for both recreation and irrigation, but water has been eroding the riverbed behind it for over a decade. If no maintenance is performed, the structure could collapse entirely, eliminating both its recreational value and its utility as a water diversion.

Understanding how one of Missoula’s signature assets became a maintenance orphan requires going back some 20 years, when building the wave seemed like the hard part.

Before Brennan’s Wave was constructed, the original diversion adjacent to Caras Park — a tangle of concrete and rebar — presented a significant hazard to river users.

Missoula attorney and kayaker Trent Baker and others formed a small nonprofit called Brennan’s Wave, Inc., named after professional kayaker Brennan Guth, who died in a kayaking accident in Chile in 2001. Before his passing, the two had brainstormed how they might repurpose the diversion. Afterwards, Baker and co. went about bringing the vision to life. Their nonprofit worked to obtain a 310 permit from Missoula County, required by Montana’s Natural Streambed and Land Preservation Act for any activity that alters a perennial stream. Between 2003 and 2006 the group raised enough money — including Missoula Redevelopment Agency funding and a donation from the Dennis and Phyllis Washington Foundation — to make the wave a reality.

It wasn’t uncommon in the first first few years after the wave was installed to see 30 kayakers lined up in the eddy to surf what was, back then, a perfect river wave. Since then, the river has become cleaner, too. Beginning just two years after the wave’s installation, in 2008, and about 7 river miles upstream, the removal of the Milltown Dam — and with it a century’s worth of toxic contamination that had accumulated there — invited people back to a restored Clark Fork.

“Since Milltown Dam came down, pollution levels are down and it’s safer to boat [on the Clark Fork],” says Steve Gaskill, a retired UM professor. “Missoula has a great shared vision, and the river’s a big part of it.”

In 2015, Gaskill conducted a study of Brennan’s Wave’s economic impact, finding that it generates at least $2.8 million annually in tourism and commerce.

“With anything promoting Missoula, there’s a 50/50 chance it mentions Brennan’s Wave, which really says it’s an image that’s selling Missoula,” Gaskill says.

“With anything promoting Missoula, there’s a 50/50 chance it mentions Brennan’s Wave, which really says it’s an image that’s selling Missoula.”

The study counted an average of 67 wave users per day, and a total of 9,246 between May and September 2015.

Cass Stoltzfus, director of Missoula Outdoor Learning Adventures, has been leading Clark Fork float trips through town for the past ten years.

“The tales that come from Brennan’s Wave are a gateway to empowerment, showing kids and adults alike what it feels like to conquer turbulent waters for the first time,” she says.

“I have seen terrified kids go from sitting in the bottom of the raft at the site of the old Milltown Dam … to bringing surfboards down to the wave with their friends. These are the folks who will make up the next generation of passionate river protectors in Missoula.”

But all of the wave’s value — social, economic and otherwise — hasn’t translated into a clear maintenance plan.

The question of who should pay to fix Brennan’s Wave is a bureaucratic maze involving multiple entities and muddy regulations.

Orchard Homes Ditch Company holds the water rights and owns the diversion structure itself, but maintains its responsibility extends only to irrigation function.

“Our primary obligation is to deliver irrigation water to our users,” says Michael Moser, president of Orchard Homes. “While Brennan’s Wave has become a valued recreational site for the community, we do not have operational responsibility or authority over recreational components. As of now, the diversion is functioning properly for irrigation, and our routine inspections have not identified any maintenance concerns related to that function.”

Moser indicates that, if another entity were to present the permits and money necessary to restore the structure to optimal function for recreation, Orchard Homes would cooperate in that process.

One of the required permits would come from the Army Corps of Engineers. That the agency is involved at all is one of the primary complications. Because the wave’s original construction was viewed as an irrigation diversion upgrade, it bypassed the Army Corps’ Section 404 permitting process, which ensures compliance with the federal Clean Water Act.

But then, at some point between its construction and the damaging 2011 floods, the agency began viewing the structure as a recreational feature, meaning any repairs are subject to Section 404’s stringent permitting requirements. According to Trent Baker, the agency mandated dewatering the wave for repair in a way he says was impractical and financially out of reach for the small nonprofit that raised the money to build it in the first place.

“I’d love to see [Brennan’s Wave] fixed, but we can’t spend public dollars on private infrastructure.”

The city, meanwhile, isn’t wading into the matter, citing a lack of jurisdiction. It’s a private structure built on a state-owned riverbed permitted by Missoula County and governed by state and federal law.

“I’d love to see [Brennan’s Wave] fixed,” says Morgan Valliant, the city’s ecosystem services director, “but we can’t spend public dollars on private infrastructure.”

Repairs are further complicated by bull trout. Much of the Clark Fork River Basin is considered critical habitat for the native fish, which has long been listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act and, according to state scientists, continues to suffer “severe declines” in its remaining Montana refuges. Regulatory agencies are hesitant to grant any stream permit that might conflict with ESA mandates.

“The ESA creates a lot of mechanisms to govern anything that affects critical habitat,” Jock Conyngham told me in 2015, at the time a research ecologist with the Army Corps of Engineers. “Bull trout move over big geographic areas, and anything that creates a fish passage issue is going to be looked at with a very hard eye.”

Pat Saffel, fisheries program manager for Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks — which advises counties during the 310 permitting process — recalls a conversation he had with an engineer during the initial permitting of Brennan’s Wave.

“When you put this grout or concrete in the riverbed, it’s like putting concrete on marbles — those marbles are going to shift,” he says. “Rivers are dynamic, and when you try to build something in them that’s supposed to stay where it is forevermore, that’s really hard.”

“When you put this grout or concrete in the riverbed, it’s like putting concrete on marbles — those marbles are going to shift.”

We must remember, Saffel adds, that an urban river doesn’t follow the same rules as a natural river. The Clark Fork through Missoula is straightened, channelized, missing its natural meanders and side channels.

“In the city, [the river’s] locked in,” he says. “With big flows, it’s going to scour down, not side to side. It’s going to stay in its channel, and this puts more pressure on the [wave] structure. Those marbles start to move.”

For now, the wave continues to function, drawing crowds of surfers, kayakers and onlookers to the heart of downtown. But each spring runoff brings fresh questions about how much longer the structure can withstand the river’s patient but persistent efforts to reclaim its channel.

As Saffel puts it: “A river will be a river — and it’ll rearrange things.”

Second wave, second chance

Even as Brennan’s Wave faces an uncertain future, Missoula has been pursuing plans for a second surf wave downstream — a project that has evolved from grassroots passion to municipal planning over more than a decade, learning hard lessons about the complexities of building in riverbeds along the way.

Just a few minutes’ float downstream of Brennan’s Wave, the Clark Fork is littered with in-stream detritus and the shark-toothed remnants of another old irrigation diversion. For over 10 years, a coalition of river enthusiasts advocated to clean up this reach of river and install Missoula’s second engineered surf wave. They called it Max Wave, named after local kayaker Max Lentz, who died on West Virginia’s Gauley River in 2007 at the age of 17. The project’s slogan captured the community’s broader vision: “Face the River.”

After raising hundreds of thousands of dollars to pay for engineering plans and initial environmental impact studies, however, the Max Wave coalition ran aground on some of the same regulatory rigmarole that plague Brennan’s Wave repairs.

“I’m kind of out of juice,” says Jason Shreder, who served as president of the Max Wave. “There aren’t many things in my life I can say I started and didn’t finish.”

“There aren’t many things in my life I can say I started and didn’t finish.”

Shreder says the Max Wave spent all the funds they raised going in circles with engineering firms and regulatory agencies. Despite the best intentions of all parties involved, none of the designs and impact studies they commissioned remained relevant as the process grew more complex and the volunteer-driven effort proved inadequate for navigating federal permitting.

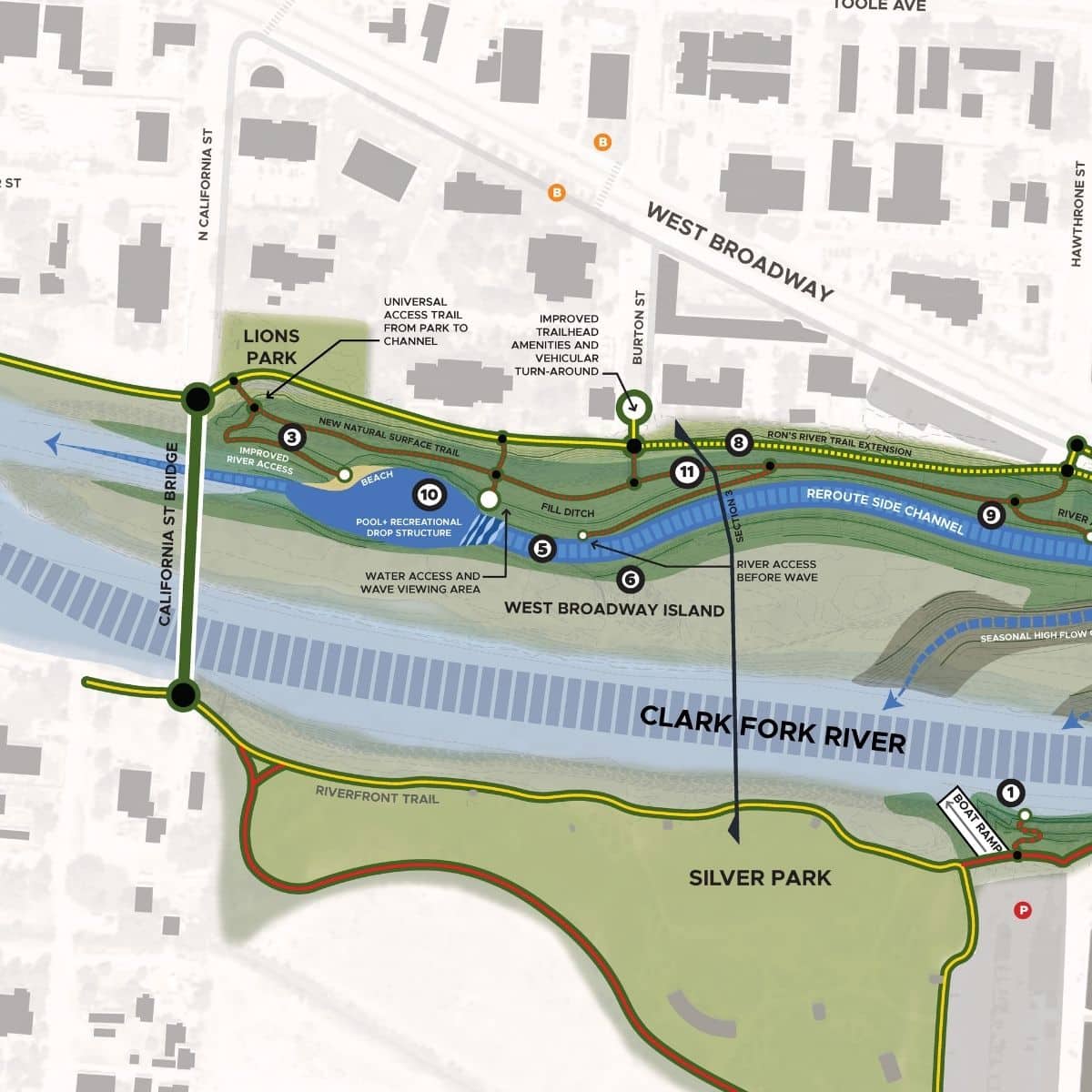

But the Max Wave vision lives on in the city’s West Broadway River Corridor Project, a comprehensive and collaborative effort to revive the 0.4-mile stretch of river between McCormick Park and the California Street Bridge. It’s about improving the whole corridor, not just building another surf wave — though a new wave is among the features the city’s floating.

The city’s now three years into the West Broadway River Corridor Project’s master planning process, funded by tax increment financing (TIF) dollars from the Missoula Redevelopment Agency. The project centers on the West Broadway Island, a roughly five-acre patch of flood-prone ground made into an “island” by an irrigation ditch. The city purchased the land in 2011 and it’s worked to improve access and restore vegetation, but it remains an urban no man’s land where a recent spring cleanup collected three tons of garbage from homeless encampments.

Morgan Valliant, the city’s ecosystem services director, says he’s empathetic — Missoula’s in the throes of a housing crisis and shelter beds are only becoming scarcer — but ultimately his responsibility is to the river.

“When I see clearcutting of the riparian vegetation, and human waste, and debris flushing downriver, my answer is always, you should not camp there,” Valliant says. “It does not matter if you’re camping or recreating — you have impacts.”

The draft master plan lays out three design concepts for cleaning the river and its banks, improving recreational access, and making the area safer. They all include rebuilding the Silver Park boat ramp, removing the Flynn-Lowney irrigation ditch, which the city acquired in 2021, and revegetating the banks with native species.

The third and most popular design — favored by 79 percent of people who responded to a 2024 city survey — also includes a surf wave. It would be built in a new side channel where the existing irrigation ditch runs, but cut wider and deeper to capture year-round flow. Existing bridges to West Broadway Island would be removed, preserving it as wildlife habitat with only “float-in” access. That design is also the most expensive of the three — $5 million to $7 million, the city estimates.

FWP’s Pat Saffel says that decommissioning the Flynn-Lowney diversion is what makes the West Broadway project viable in ways that the Max Wave wasn’t.

“With Max Wave, we were pinched — we had erosion on the south bank, an irrigation ditch on the north bank, and demand for recreation in the middle,” he says. “That’s a lot of needs, and not much space. We were asking a lot of the river in that section.”

Trout Unlimited senior project manager Rob Roberts, who’s leading the West Broadway effort, acknowledges the federal funding landscape is “not great.” Best case scenario, he says, is that construction begins in 2028.

Unlike the much more narrow process of building Brennan’s Wave, the West Broadway River Corridor Project will include a comprehensive maintenance plan. It’s informed by TU’s hydraulic modeling that shows where sediment might pile up, and they’re vetting various materials and their implications for long-term maintenance.

“It’s hard to predict in a natural river system what problems will arise,” Roberts says. “This is a piece that has drawn out the project, but it will be worth it in the long run.”

Valliant emphasizes the inclusive nature of the project’s planning.

“We’ve met with everybody — recreationists, people doing programming, local businesses, the disabled community, the Salish-Kootenai Tribal committee,” he says. “We’re coming up with a really well-supported community vision that’s going to be the largest project we’ve done in downtown Missoula since we built the levees in the 1960s.”

Valliant anticipates the city will finish the final master plan and open a public comment period by the end of summer. But the critical next step, whether the project ends up featuring a surf wave or not, is securing funding.

I asked John Lentz, Max’s dad, if there’s a world in which a new wave, even if it no longer carried Max’s name, might yet contain his son’s legacy.

“Maybe,” Lentz said. “Max used to love, in high school, going to Brennan’s Wave. It’s a nice thing for young kids to have access to. If the city goes ahead and builds [another wave] and it doesn’t have his name on it, that’s their choice, and it would still be a good thing for the community.”