Back in late April, a new state law to strengthen background checks for public school employees and volunteers came sailing out of the Montana Legislature with unanimous bipartisan support. Lawmakers and public education advocates alike framed it as a common-sense piece of legislation, the type of measure that would ensure greater protections for K-12 students.

That legislation is one of a host of statewide changes now taking root at the local level as trustees of the Missoula County Public Schools prepare to adopt more than two dozen revisions to the district’s policy books during their Oct. 14 meeting. The 2025 Legislature proved among the most significant sessions for education policy in recent memory, and the proposals before Missoula’s board mark a final step in implementing a raft of new state laws involving early childhood education, suicide prevention, gender identity instruction, artificial intelligence, and student safety.

In many cases, MCPS Superintendent Micah Hill said in an interview with The Pulp, the district’s policy revisions are straightforward and mostly technical, even when the laws themselves drew considerable attention or controversy. For example, the Legislature’s effort to bolster math skills among preschoolers — one of the session’s most celebrated education bills — called for MCPS to do little more than add half a dozen new words to local policy and strike out a few others. Likewise, when Republican lawmakers passed a controversial ban on flags representing “a political party, race, sexual orientation, gender or political ideology” in schools, MCPS didn’t have to overhaul its rules to comply — only making minor wording adjustments. Hill noted that the Missoula City Council’s formal adoption in June of the Pride flag as an official city flag just after the law passed freed the district from more stringent revisions.

However, some of the Legislature’s work this year does raise fresh challenges for MCPS. District officials are currently sorting out the most effective way to implement a law requiring students to opt into classroom lessons specifically about gender identity but preserving the traditional opt-out nature of lessons involving sexual orientation and human sexuality. Although teachers are given more time to notify parents of such lessons than under sex ed laws passed in recent past sessions, Hill noted compliance will likely prove an adjustment for district staff.

“If there were, for example, a novel that was taught in an AP Literature class and it had themes of transgender issues, that would be considered [identity] instruction and you would have to send notice to a parent to say you don’t get to opt out, you have to opt in,” Hill said. “It’s a different type of requirement, so I think that’s created a little bit of a challenge for us.”

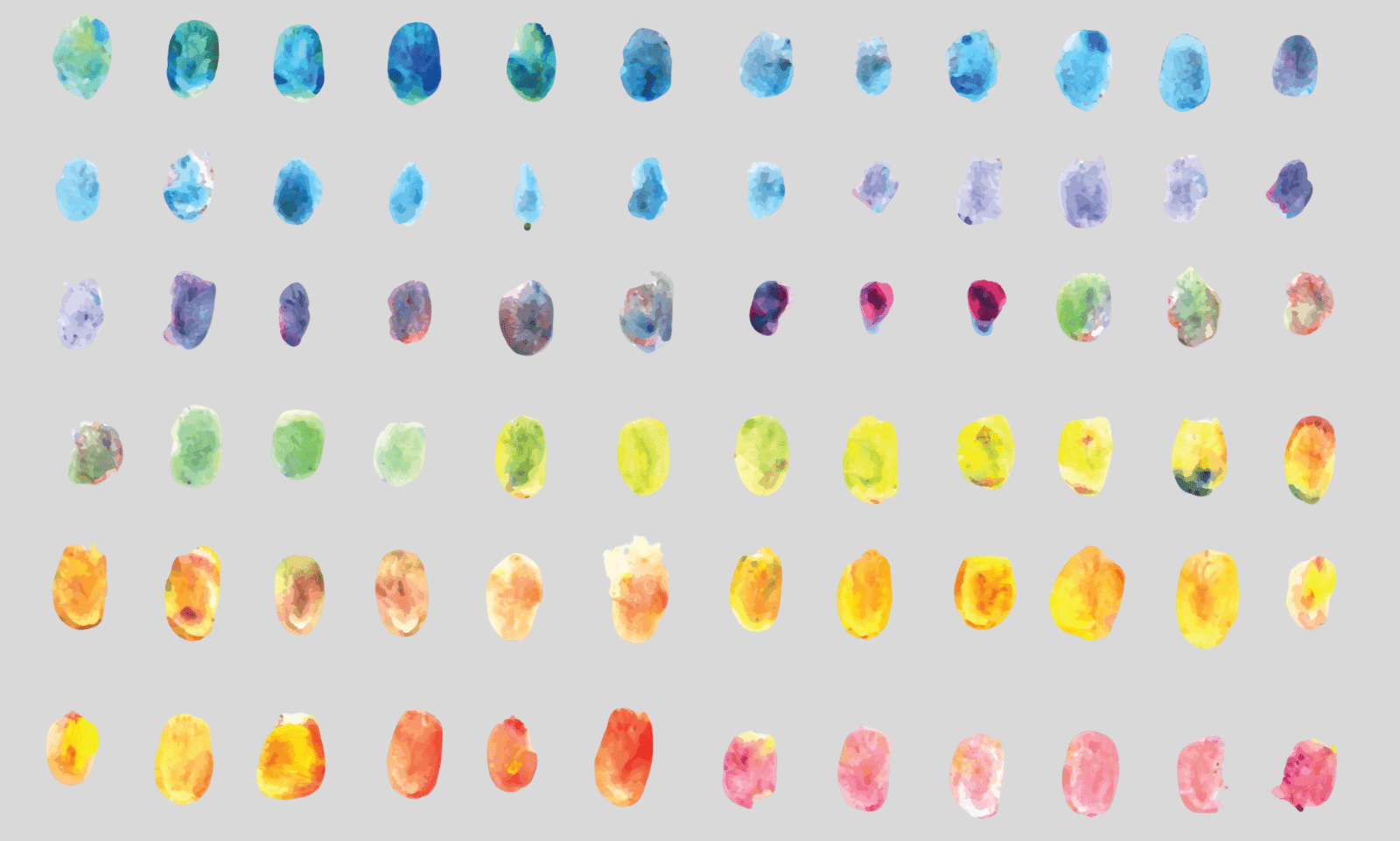

The law that’s truly “wreaking havoc” now, Hill said, is the same one that received such strong support during the legislative session: the new background check requirements. The law — which is an act revising an already existing background check law — is meant to create a uniform standard for background checks across every district in the state and reduce liability exposure for schools. Central to the new act is a requirement for anyone with unsupervised access to students to undergo a fingerprint-based check through national criminal databases. While Hill supports the goal of protecting students, the local application of more rigorous screening this summer and fall quickly revealed how large-scale and costly the undertaking would be.

Hill estimated the district has roughly 4,000 volunteers doing everything from coaching sports teams and tutoring students to running hallway coffee carts. Then there are the third-party contractors who routinely tend to vending machines, plumbing, ventilation and other maintenance needs.

The district has long relied on name-based background checks through state databases to screen volunteers. This fall MCPS is instead running its own centralized fingerprinting operation during four-hour blocks each day to comply with the new law — a process Hill acknowledged has been bumpy so far.

“My daughter volunteer-coaches for Big Sky [High School],” Hill said. “She had to come in, and they said, ‘We’re open from 10 to 2 for fingerprinting.’ She shows up at 10:10 and she waits two hours to get her fingerprints done. And it’s 30 bucks a whack for us. We’re paying for it.”

MCPS Communications Specialist Jennifer Savage told The Pulp the district has so far spent roughly $12,000 to run slightly more than 500 fingerprint checks. Lawmakers had briefly discussed the logistical hurdles of fingerprinting school volunteers prior to passing the bill, but their questions focused mostly on the reportedly lengthy turnaround times for results. On occasions when the issue of local feasibility did come up, statewide education advocates assured lawmakers that the change would not prove overly burdensome for schools. The Legislature did not address the added costs for districts, nor did it include additional state funding to help them comply with new requirements.

“I suspect it will — whether we like it or not — turn off people who want to help because who wants to go through all that?”

Lance Melton, executive director of the Montana School Boards Association and a longtime public education advocate at the Montana Legislature, acknowledged the challenges of ensuring that every third-party contractor or parent chaperone is fingerprinted. Montana’s new background check requirement sprang from the best of intentions, Melton said, and no one is questioning the goal of keeping students safe. It’s all about risk management, he said. As head of the organization that crafts model policy for local boards to use, Melton said he encourages MCPS and other districts to consider when fingerprinting is necessary and when the guarantee of line-of-sight supervision can suffice.

“There’s different ways to crack this nut,” Melton said, “and it’s not the sole means of doing so to go out and fingerprint parents and then have them sit in on one class.”

MCPS Board of Trustees Vice Chair Jeffrey Avgeris has been contemplating that exact point as he’s mulled the district’s proposed new policies for complying with the law. He said he believes fingerprint checks are an “excellent idea” to reassure parents that Missoula schools are a safe and trustworthy place for their kids. But Avgeris estimated the cost will be roughly the equivalent of a teacher’s salary, and even the potential remedies come with downsides.

“There’s definitely ways and strategies that we’ve discussed,” Avgeris said of reducing the number of volunteer checks needed. “But every one of those strategies puts more responsibility on the classroom teacher or the school secretary or the school principal, because someone has to be with them all the time.”

Fellow vice chair Arlene Walker-Andrews said she’s pondered the possible impact more stringent requirements will have on volunteerism in the district. Parents looking to get involved with MCPS as coaches, hallway tutors, concession stand workers or field trip chaperones now have to show up at the administrative building during a narrow daily window, often facing long wait times.

“I suspect it will — whether we like it or not — turn off people who want to help because who wants to go through all that?” Walker-Andrews said.

Looking at the raft of new education laws the board is now tasked with implementing, Walker-Andrews categorizes them in three ways. On one side are the easier laws the board is happy to roll out, like improving early childhood numeracy. On the other are state laws that could prompt outside legal opposition but that board members, regardless of their personal feelings, are required to put into practice. The fingerprint checks are squarely in the middle category — a workable change that nonetheless presents some big near-term logistical challenges.

“We’re obviously obligated as a school district to implement these things, and if we don’t we can be recalled,” Avgeris said. “As long as it doesn’t directly affect the state and our local bylaws that say that a student should have a fair, equitable education and everyone should be included … I let people smarter than me in the legal realm tell us the legal ramifications and stuff.”

That said, Melton equated local school boards to a sort of “fourth branch of government,” given their powers under the Montana Constitution. There are instances when trustees may strongly disagree with the Legislature’s approach and take independent action. The MCPS board is in the early stages of doing just that, having unanimously joined a lawsuit last month challenging the adequacy of state funding for public education — even as board members acknowledged the Legislature’s recent $100 million package to boost teacher pay.

Walker-Andrews partly tied the decision back to a persistent dilemma trustees face: carrying out state laws that impose new costs on districts — such as expanded background check requirements — enacted by the very Legislature that controls their funding but that often provides no additional support.

“One reason for the suit is the feeling that there is so little local control when you have no money, that you can’t make decisions about should we do X or Y — other than which one’s cheaper,” she said.

The Missoula County Public Schools Board of Trustees meets Oct. 14 at 6 p.m. at Seeley-Swan High School to field final public comment and vote on the proposed policy revisions.