It’s a routine road-trip gag to pull on visiting relatives during a tour of the Rocky Mountain Front: Head north from Bowman’s Corner about 12 miles, past the Milford Hutterite Colony, and casually point out the chain-link fence square atop a little knob just off the right side of Highway 287.

“That’s where we plant the nuclear missiles.”

Let the leg-pulling accusations of Western tall tales roil for a few more miles until another chain-link compound appears on the left — with American flags flying and an occasional U.S. Air Force Humvee parked in front of a couple drab military barracks. No bluffing.

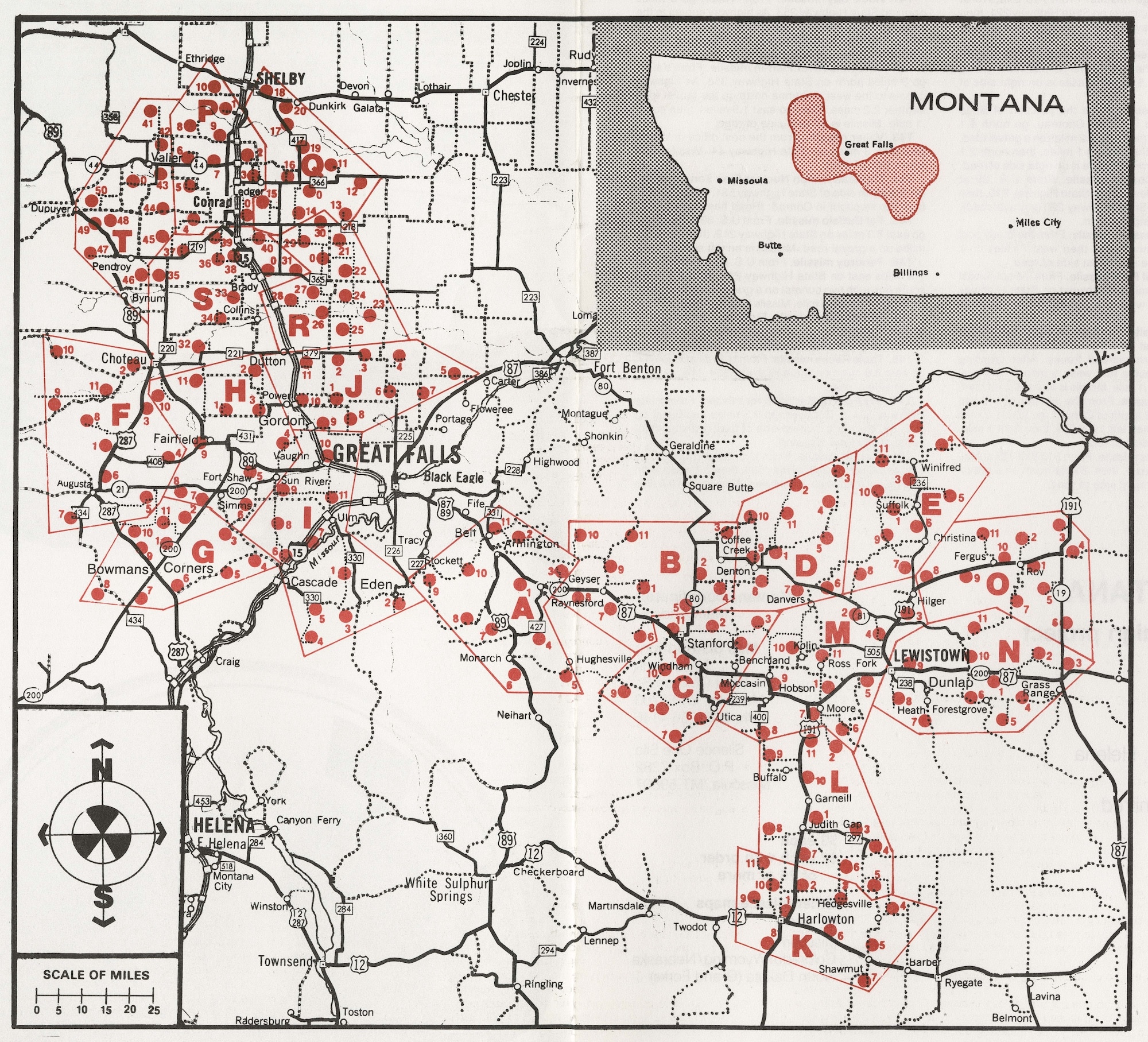

There are 150 intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, silos dotted across the central Montana landscape. They conceal 60-foot-tall rockets beneath 110-ton concrete closure doors, but they’re not exactly hidden. Benchmark Maps’ Montana Road and Recreation Atlas has them all marked. You can spot them on Google Earth.

Like grizzly bears and anti-government militias, nuclear bombs are a rare but real part of the Montana landscape. They have been almost since we first split atoms for war. Strategic thinkers in Washington, D.C., debate game-theory scenarios of nuclear deterrence. Children in Lewistown have a playground with a decommissioned Minuteman ICBM next to the swing set. Their parents are negotiating with U.S. Air Force real estate agents about new silos and service corridors expected later this decade. Their grandparents drank milk contaminated with radiation from the first nuclear bomb tests blown a thousand miles downwind from Nevada in the 1950s.

On Jan. 28, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved their Doomsday Clock one second closer to midnight. That symbolic action reflected real events in world affairs, according to Scott Sagan, of the Center for International Security and Cooperation.

“This is not a prediction of next year, but what has happened over the past year,” said Sagan, who was part of the review team that adjusted the clock. He listed the factors: Russia’s precarious stalemate fighting Ukraine, multiple violent disruptions in the Middle East involving nuclear ambitions of Israel and Iran, Chinese military and nuclear buildups, expiring nuclear treaties, and a host of secondary concerns about how smaller powers are reacting to the rattling of big nuclear sabers.

On top of all that came the inauguration of President Donald Trump, who in his second-term spurt of orders and declarations, has moved in two distinctly different directions across the nuclear landscape.

On Jan. 28, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved their Doomsday Clock one second closer to midnight. That symbolic action reflected real events in world affairs.

On one hand, Trump announced plans to build an Iron Dome for America — a “next-generation missile defense shield.” In the game-theory world of nuclear deterrence, an impenetrable defense codes as an offensive move — inspiring opponents to build more/better first-strike weapons to nullify the shield.

Yet Trump also declared his intentions to reduce the risk of nuclear war. Toward the end of his Jan. 23 video appearance at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Trump said he and Russian President Vladimir Putin had been talking about “cutting way back on nuclear.”

“And I think the rest of the world, we would have gotten them to follow,” Trump told the assembled elites. “And China would have come along too. China also liked it. Tremendous amounts of money are being spent on nuclear, and the destructive capability is something that we don’t even want to talk about today, because you don’t want to hear it. It’s too depressing.

“So, we want to see if we can denuclearize, and I think that’s very possible. And I can tell you that President Putin wanted to do it. He and I wanted to do it. We had a good conversation with China. They would have been involved, and that would have been an unbelievable thing for the planet.”

“I personally think Trump would love to get a Nobel Peace Prize,” Sagan said. “He does have incentives to be a peacemaker and a deal maker. He would like to do that.”

Mind bombs

That could turn a planned upgrade of Montana’s missile field into a different kind of global bargaining chip. The actual missiles in those silos carry actual nuclear bombs. A test flight last November showed a Minuteman III traveling 4,200 miles from the California coast to the Kwajalein Atoll near the Marshall Islands and placing three mock warheads on the Ronald Reagan Test Site in 30 minutes. The real W87 Mod O warhead has a 300 kiloton explosive yield — 20 times bigger than the Little Boy atomic bomb that erased Hiroshima 80 years ago.

But the idea of those missiles has even more power. How many missiles each side has, how many bombs each missile could carry, how many more might be built, how much bigger or more accurate the warheads could become — all turn into bets and bluffs in the great poker game of international nuclear strategy.

Contemplating nuclear war seems to generate multiple-personality disorder. Trump has declared his intention of making the U.S. military unbeatable and foresworn cuts to its budget. But he’s also condemned “wasteful” government spending in general and vowed to eliminate it. The same day Trump announced the ICBM defense shield plan (now renamed “Golden Dome”) his Office of Management and Budget ordered suspension of funding for numerous other programs designed to reduce the risk of nuclear war. On Feb. 13, the National Nuclear Security Administration fired about 300 of its 1,800 employees as part of a federal-government-wide reduction in force. Five days later, the agency scrambled to rehire them after realizing they were the people charged with building and maintaining the nation’s nuclear bomb supply.

The Air Force plans to replace its 450 Minuteman III missiles with a new Sentinel missile program using the same silo network in Montana and across the Great Plains. But last January, it had to tell Congress the Sentinel’s cost had jumped 37 percent, from $118 million per missile to $162 million. This qualified as a “critical breach” of contract, “which requires the Secretary of Defense to certify that the program is essential to national security, has no cheaper alternatives, and cannot be terminated,” according to the U.S. Naval Institute. “It also mandates that DOD develop and validate new cost estimates and program milestones and submit this information to Congress.”

The Biden administration approved $3.7 billion for Sentinel development in its 2025 defense budget request, along with $1.1 billion for the Department of Energy to continue work on the W87-1 nuclear warhead the ICBM would carry. That was despite a subsequent report in July showing the whole program was actually 81 percent over estimated budget and three years behind schedule.

A third of those Sentinel missiles would come to Montana. Fergus County would get several dozen of those upgrades, which potentially include new silos, underground communication lines and 300-foot-tall communication towers, all surrounded by 2-mile “standoff” zones where military helicopters can fly security missions.

At a January 2024 town hall meeting in Lewistown, several residents told the Air Force they fully supported the military and the missiles. But they weren’t happy about the potential of losing electricity-generating wind turbines on their land.

“We had a potential wind farm project going to be built near my farm and ranch,” Montana Farmers Union President Walter Schweitzer told the Missoulian newspaper. “We’d met with the developers, signed an initial agreement to develop, and then they came back and blacked-out large areas on my farm where they would not put a windmill. It was a missile site on my neighbor’s place that stretched over my property. It’s a potential loss I’d incur.”

Other ranchers warned the Air Force to prepare for buying easements for many other impositions the ICBM system would impose. Would cows be able to graze under the comms towers? Would the county get to co-locate public internet fiber with the underground lines? Who would handle road repair and law enforcement when a 3,000-worker “man-camp” temporarily set up shop to build all this stuff?

‘Montana is at such peril’

Down the road in Great Falls, another group of objectors focused on a bigger question: Why use nuclear arms at all? What’s the upside of being the nation’s “nuclear sponge?”

That’s the strategic assumption embedded in the sprinkling of missile silos across huge swaths of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, North and South Dakota, and Nebraska. An enemy bent on beating the United States would have to rain hundreds of its own nukes down on (relatively) empty prairie to ensure those Minuteman IIIs or Sentinels wouldn’t incinerate its own cities.

Carol Bellin was one of the protesters holding signs and candles at the Great Falls High School public meeting where the Sentinel construction project was discussed in 2024. At 72, the former director of the Jeannette Rankin Peace Center was no newcomer to the topic, having spent five days in the Pondera County Jail for trying to block a train carrying nuclear bombs through Conrad in 1984. Her protest sign read: “In 1944 the trains brought the people to Auschwitz. In 1984, the White Train brings Auschwitz to the people.”

“The Russians knew exactly where these missiles are,” Bellin said of her time by the silos. “It’s the American people who didn’t. The more people who stood up close to the missiles and learned how much it was costing, and learned it was an extinction event if we launched these things — Montana is at such peril.”

This opens a mind-bending can of nuclear deterrence worm logic. At an Outrider nuclear weapons conference in Washington, D.C., last December, 2017 Nobel Peace Prize winner Beatrice Fihn recounted how the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons gave the war game advocates a sort-of “Emperor’s New Clothes” moment.

ICAN had tried to convene an international conference to consider a treaty for elimination of the warheads. None of the nuclear-capable governments accepted the invitation. So instead, ICAN gathered a roomful of peace advocates who publicly criticized the concept of nuclear brinkmanship. It drew outrage from the nations that didn’t show up.

“It showed how uniquely vulnerable nuclear weapons are to people’s opinions,” Fihn said. “[Government representatives] told us, ‘What you’re doing is sabotaging our security. You’re convincing people that nuclear weapons don’t work and won’t deter, and that means they’re not going to deter.’”

“It’s a perception thing,” Fihn concluded. “If a couple underfunded NGOs can deter your security system, you might want to change that.”

At that same D.C. conference, retired U.S. Strategic Commander Gen. Robert Kehler ran through the military’s perception of its nuclear duties. The baseline, said the man who spent 7 and a half of his 39-year career as an ICBM crew member at Montana’s Malmstrom Air Force Base, was that “nuclear wars cannot be won and must not be fought.” That was the joint opinion of President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev back in 1985.

Nevertheless, Kehler said, today’s U.S. nuclear policy is predicated on deterrence, and its day-to-day mission is readiness. Hundreds of missileers sit in underground control centers, testing their launch gear and drilling for launch orders. Those orders can only come directly from the president of the United States, who by law is the only person with authority to use nuclear weapons. That authority is unique — it goes directly from the commander in chief (the president) to the forces. And it is only for a specific weapon, a specific target, for a specific amount of time.

“Character is important in the chain of command,” Kehler added. “That’s why the service academies have the motto ‘We don’t lie, cheat, steal or tolerate those who do.’ It’s all part of trust and confidence in the chain of command.”

Outdated ideas

Jan. 31 marked the 75th anniversary of President Harry Truman’s 1950 announcement the United States would develop a hydrogen bomb. Truman had made the decision to drop the fission bomb “Little Boy” over Hiroshima, Japan just five years before, splitting atoms to destroy a city and break Japan’s will to keep fighting World War II. But U.S. atomic exclusivity crumbled in 1949 when the Soviet Union exploded its first fission bomb. So the Atomic Energy Commission got to work on a “superbomb” that would use nuclear fusion to smash atoms together instead of splitting them apart. That yielded a 10-megaton weapon with roughly a thousand times more power than Little Boy unleashed.

Bellin grew up during Truman’s shift from the Atomic Age to the Nuclear Age. On March 3, she attended the ICAN Nuclear Ban Week in New York City, accompanied by fellow Missoulian and UM Students for Nuclear Disarmament member Finn Mead. At least 17 people got arrested during Ash Wednesday protests outside the U.S. Mission to the United Nations.

The Japanese coined a word for the survivors of those atomic attacks: Hibakusha. At the conference, Bellin encountered new versions of hibakusha. She met Aborigines from Australia who’d been blinded by the blast-blown grit of atmospheric nuclear tests in the Outback. She met victims of radiation sickness from the Marshall Islands, where American bomb test waste was mixed in concrete and dumped in an old volcanic crater that’s now waterlogged by sea level rise. She met a delegation from Kazakhstan who told of the damage left behind by old Soviet nuclear tests on their homeland.

“Those are all victims of the nuclear weapons chain,” Bellin said. “From the people poisoned from uranium mining on up, they’re hibakusha too. Those were new things to me. It’s so heartening they’re understanding it now.”

Ground-based ICBMs are one leg of the U.S. nuclear triad — a defense strategy that adds nuclear-armed aircraft and missile-carrying submarines as a show of unbeatable deterrence. Anyone attempting to destroy the U.S. population would never neutralize all three legs, and any one is enough to destroy any adversary’s civilization.

That strategy has decayed on multiple points. Gen. Kehler pointed out the aircraft leg had been taken off its immediate response role, and no longer has the fuel tankers in place to enable a long-range bomber to reach its target without lots of advance planning. Bomber aircraft have also been notably absent in the Ukraine/Russia conflict, where the latest anti-aerial defenses have gotten a battleground workout.

At the same Washington, D.C., Outrider conference, retired nuclear submarine commander Karl D’Ambrosio revealed the challenges of a new threat — climate change. Shifts in global ocean temperature and salinity have degraded submarine sonar capabilities, making it much harder to detect enemy underwater activity. Rising sea levels and more-powerful hurricanes have put coastal military bases at risk. For example, Hurricane Michael destroyed Florida’s Tyndall Air Force Base in 2018, taking almost 10 percent of the U.S. F-22 fighter plane inventory in the process.

“This is not just a U.S. problem,” warned Jamie Kwong of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Nuclear Policy Program. A wildfire nearly incapacitated a Russian nuclear missile silo, she said, and nuclear facilities in Pakistan, North Korea and India are all vulnerable to flooding.

Then there’s the theoretical problem. Minuteman IIIs, Sentinels and similar ICBMs devolve from a nuclear strategy assuming a fight for world domination with one opponent. President Truman’s hydrogen bombs were aimed at the Soviet Union, in a clash between Democracy and Communism.

The next four decades of Cold War refined that strategy into a Mutually Assured Destruction posture, which led to significant reductions in nuclear arms. Once you have capacity to end civilization several times over, incentives grow to pursue other, more civilized projects.

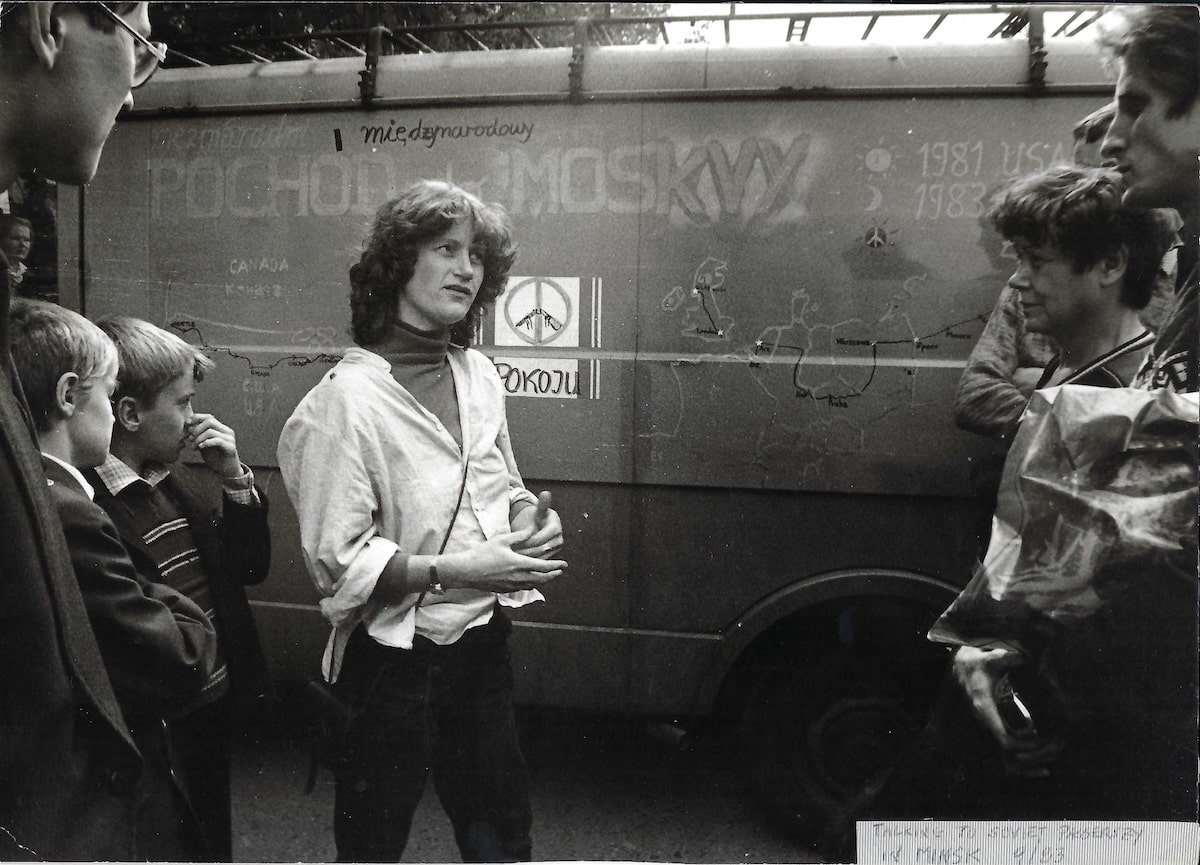

Ironically, it was a group of self-proclaimed Montana communists and peace activists who helped build public pressure for the last big reduction of nuclear weapons.

But the us-versus-them mentality is hard to shake. 1950 also brought Sen. Joseph McCarthy making his accusations that communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department. The revival of the “Red Scare” drove wedges into American politics recalling the anti-immigrant campaigns of the 1920s. Trump spent much of his last election campaign calling his political opponents “communists.”

In all three scares, the assumed targets threatened the “American way of life,” whether it was the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, the rise of Soviet Union and Communist China in the 1950s, or Chinese and European socialism in the 21st century.

Ironically, it was a group of self-proclaimed Montana communists and peace activists who helped build public pressure for the last big reduction of nuclear weapons. Missoula voters declared their city a “nuclear free zoning district” by ballot initiative in 1978. In 1982, the “Silence One Silo” campaign literally took the show on the road when University of Montana philosophy professor Brian Black and activist Karl Zanzig went looking for a protest site.

“We cruised the drag in Conrad in my yellow Datsun 1500,” recalled Black, who helped found Silence One Silo. “Zanzig noticed a shop called Day Star Solar and figured someone there was receptive to advanced environmental thinking. When they saw a couple of hippies from Missoula coming in, that was the big time.”

The solar power dealers pointed the hippies toward farmer Dave Hastings, who was not happy about sharing his land with missile silo Romeo-29. He let the group camp by his shelterbreak, which screened his house from the warhead half a mile away.

“We figured if we could get one silo shut down, that would be a step forward,” Black said. So on June 5, 1982, Zanzig and fellow Missoulian Mark Anderlik climbed over the chain-link fence and started scattering wheat “seeds of peace” on the soil around the silo. Then they sat on the lid and ate a loaf of bread baked that morning by Hastings’ wife LaVonne.

“We were sticking wheat into the cracks of the missile silo lid,” Anderlik recalled with a laugh. “Someone in the Air Force had to try and get all of that out.”

It took about an hour for Air Force security teams in armored personnel carriers to arrive and remove the “silo sitters.” Anderlik said they got lost in the backroads on the way to a military brig at Malmstrom Air Force Base. He and Zanzig were sentenced to six months in federal prison for trespassing on a federal military site.

They got sent to Lompoc Federal Prison in California, where Anderlik could watch missile test launches from nearby Vandenberg Air Force Base.

“We saw lots of little ones, and then there was a big one that was so loud that you could scream and no one would hear you,” he said. “We were sitting in one of the prison rec rooms on a Sunday afternoon watching football, and we started to feel this rumble. The building shook a bit and then it got really loud. Everyone ran to the window. We could see it take off and accelerate and then just disappear. As soon as the roar died down, one of the prisoners said ‘sons of bitches’ and people grumbled a bit and then everyone went back to watching football.”

The Silence One Silo group logged at least a dozen more arrests for silo trespass over the next two years. In 1984, as Reagan negotiated nuclear bomb numbers with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, the United States started moving its bombs around as a strategic shell game.

In 2007, the Defense Department reduced its ICBM force from 500 to 450. The New START agreement with Russia (no longer the Soviet Union) was to take effect in 2010, requiring the warhead reduction. Romeo-29 was one of the 50 silos deactivated in the process.

Except the nuclear fight is no longer just between the U.S. and Russia. Nor is it just for world domination. The chief factor limiting Ukrainian allies from greater assistance is Vladimir Putin’s threat to reach for tactical nuclear weapons. China has an estimated 500 nuclear bombs. India and Pakistan (estimated 170 warheads apiece) came close to a nuclear confrontation in 2019, according to former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. He recalled he was in the middle of negotiations with North Korea over its nuclear weapons when the Kashmir border clash nearly “came to spilling over into a nuclear conflagration.”

A regional war with tactical nuclear weapons isn’t likely to be deterred by the threat of the United States or Russia launching ICBMs onto the same battlefield. And even a small-scale nuclear clash between India and Pakistan would literally kick up enough dust to cause a world-wide nuclear winter — which is not a viable solution to global warming. The resulting airborne soot would chill the planet for at least 5 years, resulting in massive crop failure and famine. Montana’s missile silos sit amidst the nation’s biggest barley fields. As one Outrider conference attendee wagged, that nuclear winter would take out most of the nation’s beer supply.

Downwind risk

Growing up in Missoula, I walked past Meyer “Mike” Chessin’s house every weekday on the way to my preschool. His daughter Esther and I were classmates all through high school. But it wasn’t until I became a reporter and got assigned to write a profile of him that I learned Mike was one of the first botanists in the nation to find nuclear bomb fallout in milk cows.

Mike was researching the effects of ultraviolet radiation on plants when fellow University of Montana zoologist Bert Pfeiffer brought in a collection of North Dakota milk cow bones. The herd was grazing downwind of the early atmospheric nuclear bomb tests. Americans detonated 210 of them above ground between 1945 and 1962 at proving grounds in Nevada. Mike confirmed the bones were contaminated by radioactive particles blown a thousand miles downwind to North Dakota.

“By the mid-1950s, we were already detecting it,” he told me in 2017, sitting on his University Avenue porch. “North Dakota was a hot spot. We’d go around and talk to PTAs and service clubs on the biological effects of the radiation. We’d always try to be as objective as possible. But at the end, everyone always wanted to know, as scientists, were we building fallout shelters?”

Research such as Mike Chessin’s helped push President John Kennedy to ban above-ground nuclear tests in 1963. Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963. That same date is on the packing label for crates of “survival ration biscuits” packed by the Office of Civil Defense and stored in 18 fallout shelters on the University of Montana campus. An inventory in 2016 reported almost 1,000 boxes still gathering dust in various campus buildings.

Radioactive waste dating back to the Manhattan Project and other weapons research still contaminate and sicken Americans today. Other parts of our nuclear heritage aren’t so durable.

President Reagan got the Senate to pass the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty on a vote of 93-5. But President Bill Clinton lost a comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty in 1999, when 51 Republicans voted against four of their colleagues and 44 Democrats.

The last remaining nuclear weapons treaty between Americans and Russians, known as New START, expires on Feb. 5, 2026. Putin announced his suspension of participation in the treaty in 2023, a year into his invasion of Ukraine. Nuclear states around the world have an estimated 12,000 bombs of various sizes and delivery systems. About 2,000 of those are assumed to be on alert for immediate use.

Trump has also proposed withdrawing from NATO and signaled an unwillingness to extend American security guarantees to allied nations. That’s led numerous international relations analysts to forecast a growth in nuclear threats, rather than a reduction. Smaller nations will seek their own bombs when they can’t presume the big guys are making the rules.

“Nuclear weapons are all about belief in processes and institutions,” George Washington University professor and former U.S. nuclear negotiator Sharon Squassoni said at the Outrider conference. “And an arms race implies somebody wins.”

Besides the United States and Russia, seven states are known to have nuclear capability: the United Kingdom, France, China, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea. Then there are the “nuclear-latent states” — South Korea, Japan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands — which are believed capable of producing nuclear bombs. Squassoni added that growing interest in civilian nuclear energy as a way to address climate change will increase the amount of fissile material available for making bombs.

In his new administration, President Trump appears fully in line with Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s action plan for reshaping the U.S. government. One of Project 2025’s defense proposals would restart nuclear weapons testing at the Nevada National Security Site.

“Life is full of ironies,” Chessin told me shortly before he died in 2018 at the age of 97. “Reagan came within a hair’s breadth of getting a comprehensive test ban. Our military is as great as the rest of the world combined. But we say we don’t want an empire, so what do we need it for?”