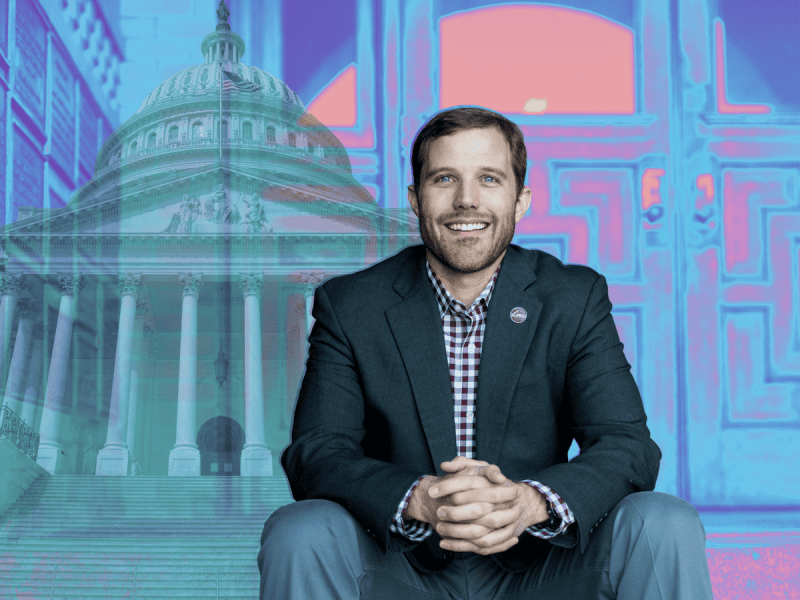

I have known Sam Forstag, a Missoula-based smokejumper, union organizer, politico and now-congressional candidate, for several years — first as a source when I had just started covering the state Capitol and when he was lobbying for the Montana chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and, later, when he was a partner in the lobby shop Central House Strategies, representing a variety of causes and clients including the city of Missoula. He was a shrewd legislative maneuverer, especially for a progressive operating in a heavily Republican environment, a good source and a strong advocate on issues ranging from criminal justice reform to local control. And during the off season, he jumped out of planes to fight wildfires across the West.

We kept in touch. I drifted out of politics reporting and he focused on advocating for his fellow firefighters as the vice president of the Forest Service Council of the National Federation of Federal Employees, Local 60. That work took on greater meaning during last year’s DOGE cuts and federal shutdown, landing Forstag on stages alongside people like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. So when, in early January, Forstag declared his intention to quit his federal position and enter the Democratic primary for Montana’s First Congressional District (a decision followed by a Sanders endorsement), I reached out for an interview. And, lest anyone think I’m being secretive, I’ll say this up front: I like Forstag on a personal level. I aim for honesty in these pages, not a false sense of objectivity.

All of which is to say I wasn’t totally surprised to end up in swim trunks sitting across from Forstag in his backyard sauna on a chilly evening in late January. We had played phone tag for weeks before he invited me over for a schvitz — an offer I took as permission to interview him in an unconventional and, shall we say, revealing setting. If “Hot Ones” can do it, why can’t we? The Pulp, after all, has the bones of an alt-weekly, and we like an off-kilter interview. Photographer John Stember tagged along, which made us both a little nervous — Forstag for reasons of public decorum, and me because I was quite sure he would look better shirtless. Nevertheless, we spent about an hour in there, the temperature climbing past 200 degrees, my pale skin turning pink, and my phone eventually overheating, which marked the end of the interview. We talked about smokejumping, his pitch to voters of all stripes, the condition of the Democratic Party, public lands, and more. What follows are highlights of our conversation, edited for clarity and concision.

About the race

The Democratic primary is crowded — other than Forstag, there’s Ryan Busse, a former gun industry executive and author who ran for governor in 2024, and two military veterans and ranchers, Matt Rains of Simms and Russ Cleveland of St. Regis. Whoever wins will face incumbent Republican Rep. Ryan Zinke, a longtime state and federal lawmaker from Whitefish who previously spent a controversy-plagued two years as U.S. Secretary of the Interior under the first Trump Administration. The First District leans solidly Republican, but Democratic strongholds like Missoula and Bozeman — plus the possibility of a midterm rebuke of the Trump’s GOP — leaves a narrow path for a Democrat to win, but not without capturing a sizable chunk of people who had previously supported Republican candidates.

The Pulp: To start, do you want to give your elevator pitch? Why run in this race? Why now? What do you bring to the table as a candidate?

Sam Forstag: I’ve worked as a smokejumper the last four years, and a wildland firefighter the last eight and, man, in the last year, we lost about a quarter of Forest Service workers in this state. And when you get the numbers of who they were firing, it’s mostly people making less than 20 bucks an hour. It’s always been the same damn story. It’s the same as when that mill closes up in Seeley, and it’s the same as when bankers drive us into a recession. It’s working people getting screwed, and somebody is getting rich off of all of this. This time, it’s just right out in the open.

People are pissed off, and they ought to be. But then, at the same time, I look around at the end of fire season, at the end of a year of fighting against this shit and hearing all these terrible stories from my union members, and it just feels like we’re about to do the same exact thing and expect a different result.

Some of the people I work with voted for Zinke and Trump and the rest of them. And, on the one hand, that is confounding, because our material interests are not served by what’s going on. But on the other hand, I don’t blame a single one of them. I don’t blame a single person who looks up after four years of Democratic control and says their life is worse and votes for the party out of power, because that’s how democracy is supposed to work, right? And the shame is that we didn’t give anyone a better option. The average member of Congress is worth 3 to 4 million bucks. And you wonder why poor and working people get left behind every year. It’s a fundamental problem of representation. There’s no actual representation for poor and working people right at the highest levels of office.

But why run for Congress? Why not run for a local office or do more policy work at the Legislature?

For the last eight or 10 years, when I was doing organizing and advocacy between fire seasons, I was the first person to tell all my coworkers or all my friends that if you want to make a difference, go get involved at the state level or the city level, because that’s where most of the policymaking that affects our life happens. And it does not feel like that in the last year. I had a member of our local who was a 15-year Forest Service employee. She took a lateral transfer so that she could do more remote work because she was undergoing chemotherapy. And Elon Musk comes in in February, on Valentine’s Day, and she gets fired with no notice and no cause. We got her job back eventually after six weeks of litigation and fighting. And those stories are all over the country. [Public lands are] about the public servants that actually make them work. Public lands aren’t just a line on a map. And we have forests without any trails crew left, without any recreation crew left.

They gut these few public services that we have for people who need them, and then they point a finger and say, ‘Oh, look, it doesn’t work.’ I’m seeing it on the front lines. I jumped a fire outside of Steamboat Springs last summer, it goes to 500 acres. Day three or four, I’m running a little task force of hand crews, and I put in an order for pumps and hoses, which is one of the most basic firefighting implements you could use. And they tell me, ‘Oh, we’re not getting that shit till the end of shift tomorrow because they closed down the gear cache in Steamboat to consolidate it down into Denver.’ So we got an overnight air mail delivery of a set of pumps and hoses to Steamboat Springs so a guy can drive them up. And now we’re not only delayed in fighting a fire for a day, but we are probably paying twice as much.

“We got artificial intelligence that can write legal briefs and code. You know what it can’t do? Stomp around in the woods with a saw and cut the tree before it’s costing you a million bucks to cut that tree.”

Again, it’s all the same story. It’s the same shit as when Tim Sheehy’s company cleared record profits, right? A U.S. Senator who’s worth between $100 and $300 million, with a company that basically only makes money off of state and federal contracts. We have the money, and we’re paying every penny. We’re just paying it out the wazoo, out of our communities, to the richest people and the corporations.

Obviously, a lot of what you’re saying is informed by time spent working in fire, working on public lands. And you mentioned the closure of Pyramid Mountain Lumber in Seeley. What are you actually proposing in terms of public lands management? Or the forest industry?

We’re talking about public lands like it’s the ‘70s. But it’s an issue for basic working-class rights. Public lands cannot just be preservation. It made a lot of sense when [the U.S. was] looking at our last one-to-three percent of old growth timber. But now, we live in Montana, we are surrounded by public lands, and we have a few mills left in this whole half of the state. And we have a housing crisis. These things are all connected.

Let’s actually talk about what reinvesting in public lands looks like. And that doesn’t mean just filling the spots in the Forest Service we lost in Montana. What that should mean is, let’s actually invest in these things up front and deal with them. Because we deal with forest management and wildfire the same way we deal with healthcare and housing. We wait until it’s a complete crisis, and then we pay for it in the least effective, most expensive way possible. It’s the same if it’s a 62-year-old woman sitting in St. Pat’s in the ER because she couldn’t afford a primary care visit as it is when you have a $56 million fire out by Helmville burning homes and ranches because we didn’t have the courage to invest up front.

It’s going to cost a lot of money, but we’re already spending the money. We spend hundreds of millions of dollars on wildfire response while courts take three-plus years to process NEPA claims. That’s not a timeline you can operate a business on. So I think we should be spending three to five times as much upfront in forest management, paying for good-paying jobs here. We got artificial intelligence that can write legal briefs and code. You know what it can’t do? Stomp around in the woods with a saw and cut the tree before it’s costing you a million bucks to cut that tree. It looks like streamlining NEPA, not by getting rid of the regulations — but shit, we got immigration courts, right? Why don’t we create NEPA courts?

This idea that through policy and planning, there’s a certain amount of American industry or manufacturing or whatever that we can bring back. Maybe this is a reflection of my suburban upbringing, but I guess I’m a little skeptical. How is this different than Trump trying to revive coal? I mean, corporate actors are going to follow a profit incentive, and it’s cheaper for the timber industry to operate in the South or what have you, right?

I think you’re completely right in a lot of regards. We’re not going to bring the timber industry in Missoula or in the Flathead to what it was in the ’50s. But that’s not the goal. Look at Pyramid. Pyramid didn’t say they closed because of NEPA. They said they closed because the people working at the mill couldn’t afford to live there. Government exists to solve problems that the market is not solving on its own, and government’s not doing that. In Seeley, that’s exactly where we could be using things like community land trusts and deed-restricted housing to make sure there’s permanently affordable housing in a place like the Swan Valley, which I actually think is the most beautiful corner of this state. And it’s not too late. This state is not Jackson, Wyoming, right? But if we don’t do anything, we sure as hell will be. And we still need to build houses, we need to transition to clean energy, and we need to do better than Democrats have done to make sure that if you’re losing a job in an old industry, that you actually directly have a job that you want in a new industry.

“If we aren’t winning working-class voters, we are literally not the party of the working class.”

My swim trunks are completely soaked through and my lungs are half-functional. My drink is warm. Sam, obviously, is used to the heat. Time for tougher questions.

You’ve been pretty open in your criticism of Democrats. And there’s been a lot of discussion recently about how able the party is, at both state and national levels, to meet the moment, how able it is to win. Jon Tester has said he wants Seth Bodnar to run for U.S. Senate as an independent, and called the Democratic Party an “anvil” in his failed re-election bid in 2024. Can you respond to this feeling about the party that’s in the air here? Why still run as a Democrat?

The national party did everything they could to make it hard for a Democrat to win in places like western Montana. I mean, Joe Biden lied to all of us, literally. And then you wonder why people are pissed when this guy’s dissolving in his suit, and I’m stuck out on the fire line with my friends who support Donald Trump, having to defend an octogenarian, right? We’re in a country of 380 million people. We can do better than that.

When I was a kid growing up, what being the Democratic Party was about, as I understood it, was being the party of the working class. And we just lost people making under $100,000 a year. If we aren’t winning working-class voters, we are literally not the party of the working class. Whatever our policy priorities are, even if the Democratic Party’s policy priorities would be relatively helpful to working-class people. It clearly doesn’t work to be the less shitty option.

And you can’t effectuate anything if nobody votes you into office.

And if you get into office and your solutions are all piecemeal and incremental — and we’re in a full-blown housing crisis where homelessness is tripling — that doesn’t cut it, man. If you are actually living this day to day, and you know the feeling in your chest when your mortgage or your rent is taking 80 percent of your income — which is my story for a lot of the last five years — that adds a sense of urgency. And clearly young people felt that sense of urgency, and clearly working people felt that sense of urgency. And clearly the national Democratic Party did not.

Tester seemed to put some of the blame for the party’s performance on “wokeness,” such as it is. Do you agree with that?

We had this huge conversation about representation in the last 15 years on the left. And it was healthy in a lot of ways. But also, it seems like we forgot about the most fundamental kind of representation, which is economic representation.

If you have a multi-millionaire running for office who has to manufacture anger about how hard it is to afford housing or childcare for the last 10 years, they probably do feel a lot more pressure to hedge on one issue or another. But I don’t want to hedge on any of this shit. You saw me. I worked for the ACLU, and I worked for homeless shelters. And I will tell people exactly what I told my coworkers on the fire line when they said something out of pocket about queer people: We don’t have to agree on everything. We just have to agree that none of that is in the top 10 list of issues making your and my life harder.

Looking around at our politics, though, it seems like there’s a lot of people — certainly a lot of Trump voters — who, regardless of their material interest, are really supportive of this cruelty and violence and extrajudicial killings that we see around us. And certainly some of those people are experiencing economic precarity. But certainly a lot aren’t. And you’ll have to win some of those people to win this race. I mean, isn’t some element of this political culture kind of unredeemable?

I think economics drives a lot of culture. And I think that part of the genius of Donald Trump is that he reflected a lot of people’s anger. And he reflected a lot of people’s anger and then redirected it at black and brown people and queer people and women and poor people. A young man without a college education in this country makes less money than they made in 1979, adjusted for inflation. When we have all this talk of grievance politics with these folks, you’re talking about it as if grievances are something that shouldn’t exist within politics. And somebody’s grievance that has been misdirected towards a woman should not exist. But if you’re making less than your dad did and everything costs more, that’s a legitimate grievance politics is supposed to address. That’s what politics is supposed to be, right? To sublimate violence.

When you don’t address these grievances, when you belittle people for holding them, they fester. And that’s completely the fault of our leaders. You’re not a bad person for being wealthy. But in this political moment, working people are not satisfied with either of their options. We need to fix that right now, because dilly-dallying is coming at the cost of the entire constitutional order here, and it’s coming at the cost of all the terrible things we’re seeing on our phone screens.

“We talk of grievance politics as if grievances are something that shouldn’t exist within politics. But if you’re making less than your dad did and everything costs more, that’s a legitimate grievance politics is supposed to address. That’s what politics is supposed to be, right? To sublimate violence.”

And I guess you don’t see a lane for running as an independent or under a third party?

For me, talking about how you make housing affordable with federal investment, or how you actually fix a broken health care system by giving everyone the option to buy into Medicare, or how you actually fix child care — no, there’s not an avenue as an independent. The really hopeful thing is, if we win this seat — when I win the seat — there are no plans from the national Democratic Party for how to win back the rural West, and that puts western Montana in a position of real power.

So, none of this really sounds that much different than how other Democrats have tried (and failed) to run in Montana recently. Like, we need straight talk, to roll up our sleeves, to appeal to rural people, to find economic common interest. It’s not like Monica Tranel and other candidates who have run against Zinke weren’t talking about affordability, or weren’t talking about Zinke owning multiple properties. And candidates have run to the middle and still lost as well. What makes what you’re saying different?

I bring a unique background and set of experiences — growing up in economic struggle, struggling in this state for the last 10-plus years, and on top of that, getting bills passed. I got a dozen bills passed, mainly with Republicans carrying them, on everything from libraries to education to criminal justice. If you cannot deliver on these promises, you don’t deserve to keep your job. We haven’t had a Democrat being really honest that there’s a full-blown crisis and a correct way you deal with a crisis if you believe it and feel it in your chest.

I want to be upfront and say yes, there’s been a housing crisis in this country and in the state, and it’s going to take a lot of resources, a lot of money. But we have the money. We just spent $1 trillion on tax cuts that go to people making over a quarter-million dollars a year. We’re just paying it to the richest people in the world, some of whom happen to be our congressmen and senators.

Just to be clear, how did you grow up? What was your economic circumstance?

My sister Sophia and I were largely raised by our mom, who was a nurse. Sophia’s a nurse at St. Pat’s now. I distinctly remember worrying that mom was working too much because she was picking up extra night shifts just to pay for Soph and me. And when my dad was getting his feet underneath him, he relied on food stamps to keep the fridge full while he got his teaching certificate and became a public school teacher. So I was raised by a single nurse and a single public school teacher, and they were both scraping by. That was 20-some years ago, and it’s so much harder to do that today. When I got here and started going to school, I was working at least two jobs at a time, sometimes three, while attending classes. And still I was lucky in a lot of ways. I remember not having enough money to buy books — books cost 400 bucks. The plan was to just not use the fucking books. I remember getting a check from my grandparents to pay for books and crying at that shit.

My phone overheats and I feel like I’m about to pass out. I’ve downed my last NA beer. Both of us are extremely red. We head inside, wait for my phone to turn back on, and finish up.

To conclude — can you talk a little bit about why you have stayed in Montana these last 10 years, why this place is important to you?

I’ve been here about half my life. I came for the public lands — I knew I loved hiking and skiing and just being outside. And I stayed for the people. Montanans are a different kind of people. When somebody’s stuck in a ditch, it’s incredible how many people pull over and pull them out. Or like when I ran out of gas up at the trail 45 minutes outside of town — I was working two jobs, took a Sunday afternoon off — and the very first car picked me up so I could hitchhike down to the gas station with my gas tank, buy a gallon and a half, and make it home. That’s different. The people here, maybe it’s a function of what it takes to make it through a hard winter — they actually care about each other, help each other, and know how to work their ass off.

Are you a community member with a story to tell? Can you tell that story to me in an unconventional location? It doesn’t have to be a sauna, and you don’t have to be a politician. But it does have to be interesting. Please, reach out!