After the woman she called “Granna” and others called “Del” died, Lynndee Bridges wrote a heartfelt, modern-day obit for Delphine Farmer—the kind that pops up on Instagram.

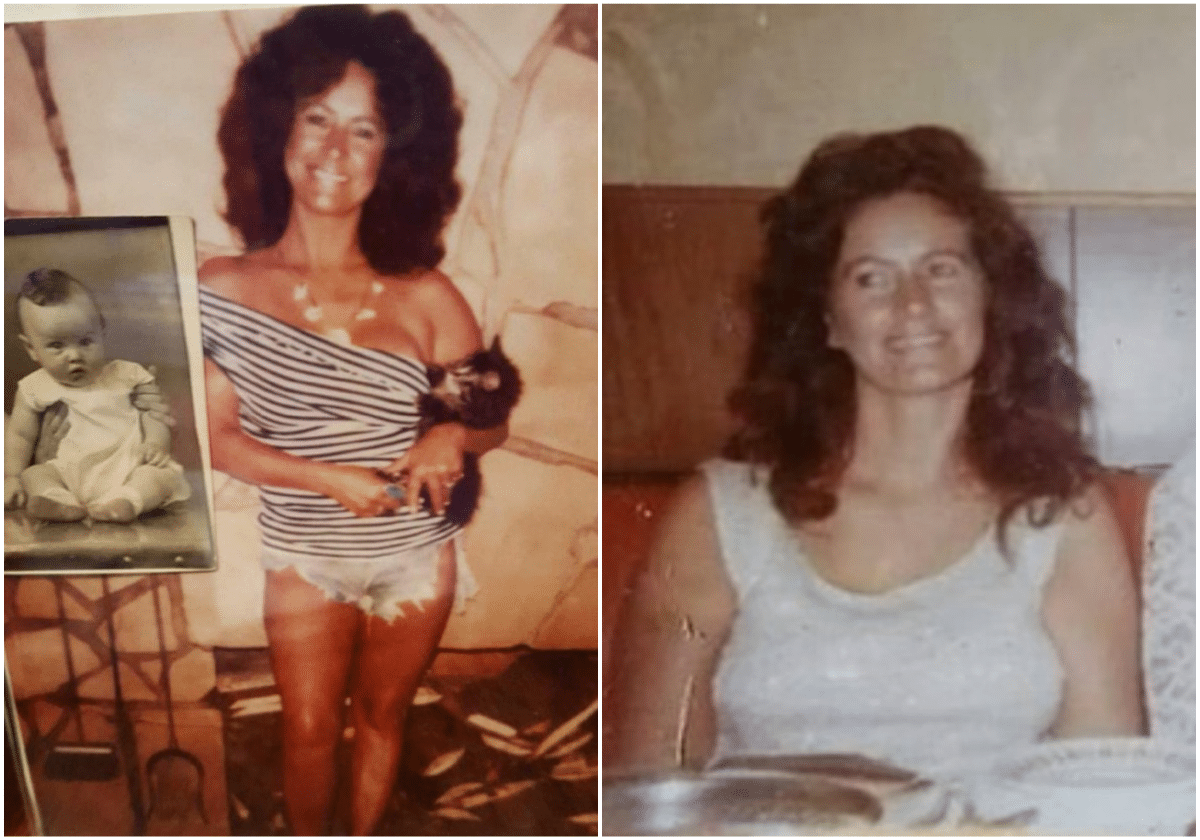

“When people post about their grandmothers, they usually say things like sweet and generous and mention delicious baked goods. But this one is different. My Granna was like no other,” she wrote. In interviews, Bridges says her grandma was bold, confident and, for much of her life, drop-dead gorgeous. She won beauty pageants and then organized them in her house, with her grandkids as contestants. She was a worker, too, and met Doug Farmer, her last of three husbands, at Champion International, the plywood plant at the old Bonner mill.

“I don’t want people to think we’re a family that doesn’t care. We really do care,” says Bridges. “We didn’t just forget this murder happened.”

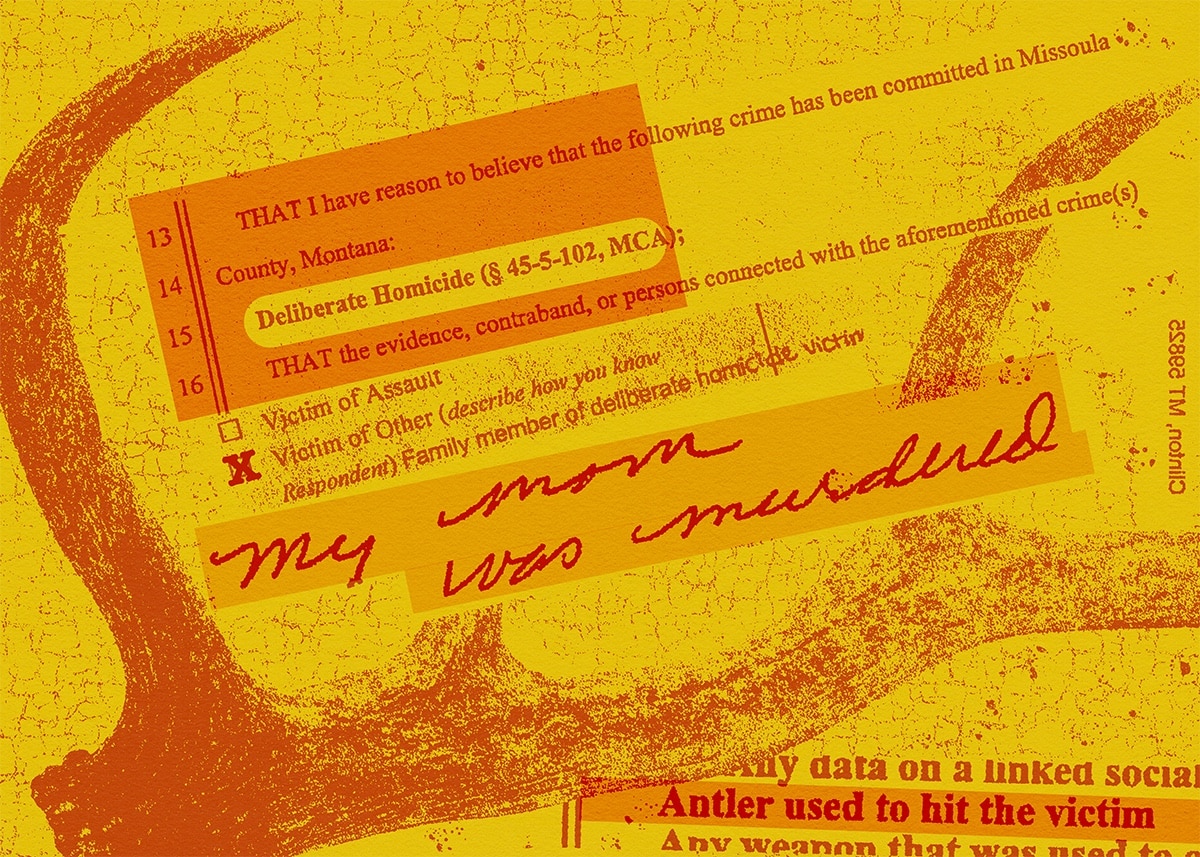

Delphine Farmer was 88 when she died Sept. 25, 2022, in what was the only homicide investigated by the Missoula County Sheriff’s Office that year. She was beaten with a cribbage board punched into an elk antler. No one disputes that. It was listed in evidence recovered from Farmer’s house and as the cause of death on her death certificate: “bludgeoned multiple times with an elk antler.” Bridges says it had been in the family a long time—a present made by her mom’s brother.

“We didn’t just forget this murder happened.”

Bridges’ dad, Shane Field, is Farmer’s son and lived in the house behind Farmer’s. His three surviving siblings all lived with their mom at the time of her death. Since then, all four have left the picturesque acres on Donovan Creek in Clinton, about a half-hour from Missoula.

Despite a detailed search-warrant narrative about what went down in Farmer’s house nearly two years ago, no charges have been filed. Two of Farmer’s children at home when she died were questioned and named in additional search warrants. Her son, Monty Field, blamed his sister, Diane Field, in a call to 911, the warrant says. According to a protective order filed on Diane’s behalf, she tells a different story.

Records show both siblings were questioned after deputies arrived on a Sunday afternoon and found Farmer bleeding on the floor, where she died. Search warrants indicate investigators collected DNA from the house and from both siblings.

Bridges says she believes Monty—her uncle—deserves a closer look, even though she’s not quite sure where he is now. He did not come to his mother’s memorial service at Missoula’s Northside Park, though her dad and both of her aunts were there, says Bridges. Her aunt Diane, who’s in her 70s, is deaf. Documents filed by the sheriff’s office describe her that way, too. Diane’s the oldest of Delphine’s six children—two preceded Delphine in death.

Delphine had Diane when she was just 14. Bridges says Diane had always lived with her mom and that now she lives with her sister, Debbie Maplethorpe, in Missoula. “In all those years of living together, there wasn’t this level of violence. And now this happens? It doesn’t make sense,” says Bridges.

Diane Field didn’t have formal schooling that taught her American Sign Language—she writes things down and acts things out, says Bridges. Both come into play when Bridges describes how Diane has communicated what happened to Delphine.

Delphine’s death happened after Debbie, who’s looked after her sister for years, briefly left the house. She did that every Sunday to play bingo at a church, says Bridges.

A hand-written note is among items taken from the house as evidence, according to a search warrant. Bridges, who says she’s talked repeatedly to investigators, says it was in Diane’s handwriting and found in her basement bedroom, and that it was about Monty; the lead investigator did not confirm or deny its contents. Bridges says her aunt Diane has also consistently acted out what happened to Delphine, blaming Monty. “She does not have the capacity to lie,” says Bridges.

In a call with Missoula County Detective Kelan Larson, Bridges says he told her he hasn’t brought charges because it’d be too difficult for a jury to understand and believe Diane. He has not responded to a request to confirm this.

“It makes me sad,” says Bridges, who’s 39, lives in Florence and is a mom to four kids. Her grandma named her Orchid Flower and rarely, if ever, called her Lynndee. She told Bridges she was a beauty queen who should be in movies. “She was an old woman,” Bridges says. “Is that the reason why they’re not doing anything? Is it the disability of Diane?”

Larson did not answer two emails, including one asking about Bridges’ recollection of their call. He also didn’t respond to a voicemail seeking general comment about the case. In January, when The Pulp published its first story about this murder, he did answer an email, referring all questions to the sheriff’s public information officer, Jeannette Smith. After multiple voicemails and emails, she texted this response: “There is no new information available in the Delphine Farmer investigation.”

But Bridges has a message for the county: Bring the charges. Regardless of what happens in the courtroom, she says her grandmother deserves at least that level of justice. And if Missoula County won’t act, “I would say, can somebody else look at it? Can we get fresh eyes? Because I don’t think that anybody working in Missoula County has a whole lot of experience with this.”

After Bridges heard from her dad how her grandma died, “I was checking the Missoula jail roster—I’m not kidding—20 times a day. I thought for sure, today’s going to be the day. It became a personal relationship I had with the Missoula jail. And it was like, just because you want something to happen, doesn’t mean it will. And then pretty soon, it doesn’t, and you know it’s not happening.”

About Delphine

Delphine Helliksen—later Delphine Field, Delphine Berry and Delphine Farmer—grew up in Minnesota and was living in Detroit Lakes when she competed in the “Queen’s Contest.” Bridges has a photocopy of a newspaper story about the pageant. Delphine is pictured in a boat, wearing a bathing suit and a captain’s hat.

Bridges remembers Delphine describing her pregnancy at 14. “She told me, I didn’t even know what was happening. I didn’t even know what it meant to have kids or anything like that. My stomach was growing and we thought it was cancer, for sure.”

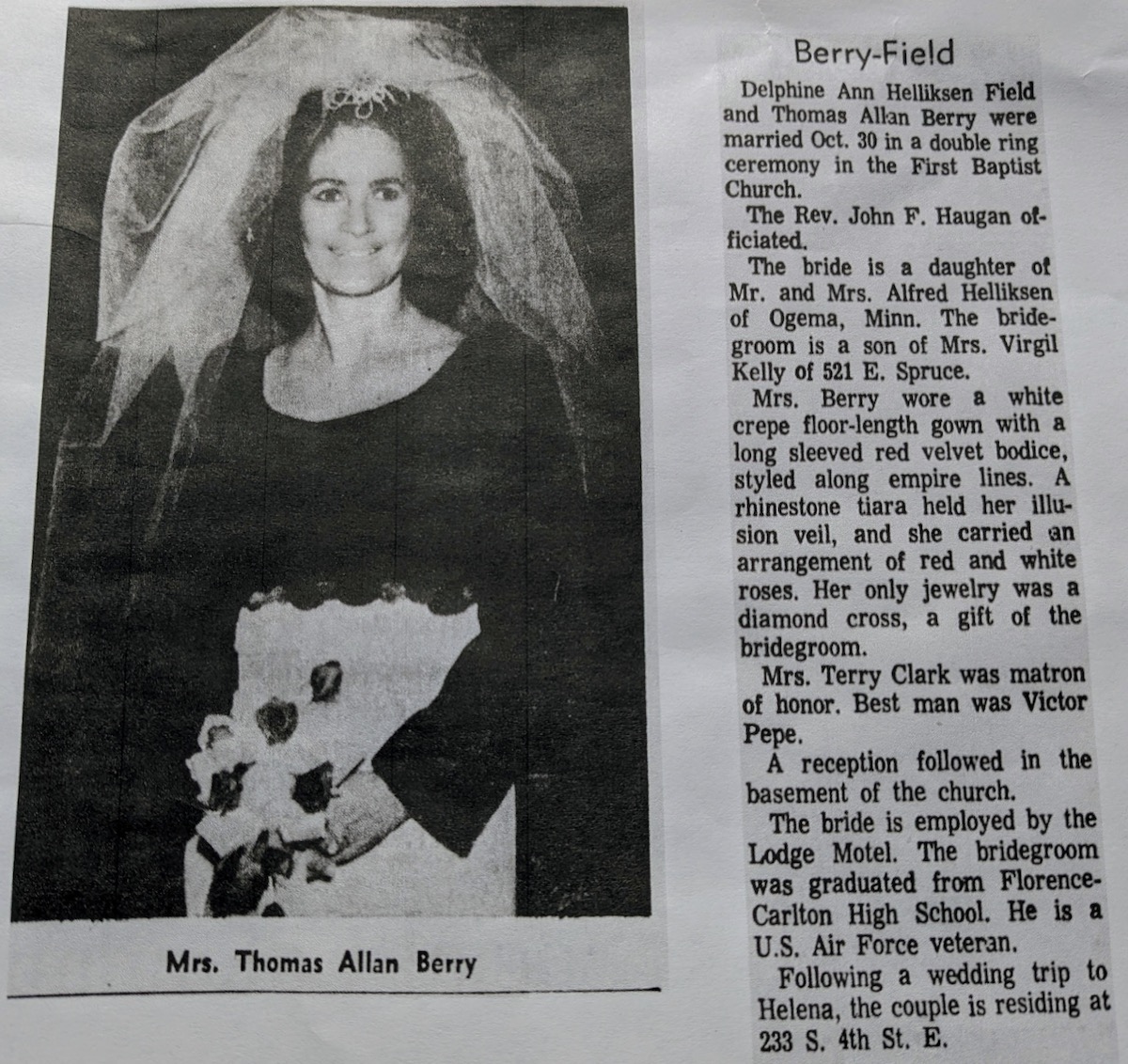

She married Chester Field and had five more children. In the 1960s, they moved to Missoula. Chester and Delphine divorced. Soon after, she married Thomas “Tommy” Berry, an Air Force vet. At the time, she worked at the Lodge Motel, according to a marriage announcement in the Missoulian. The ceremony happened at the First Baptist Church, after which they took a wedding trip to Helena and returned home to 233 S. 4th St. E.

Eventually, they settled in another neighborhood. Bridges says both her dad and her mom were Northside kids with big families—six kids in each. “They were all friends. They all kind of hung out together,” she says, and then her parents started dating, got married, had kids—living for a while near where they grew up. They later divorced and remarried.

“And I remember Grandpa Tommy working at Al’s and Vic’s. Maybe he was the manager? But we would come in there with my dad and he’d make us Shirley Temples,” Bridges says. Shane, her dad, got along well with the men his mom brought into her kids’ lives. She says he called them all dad in one way or another.

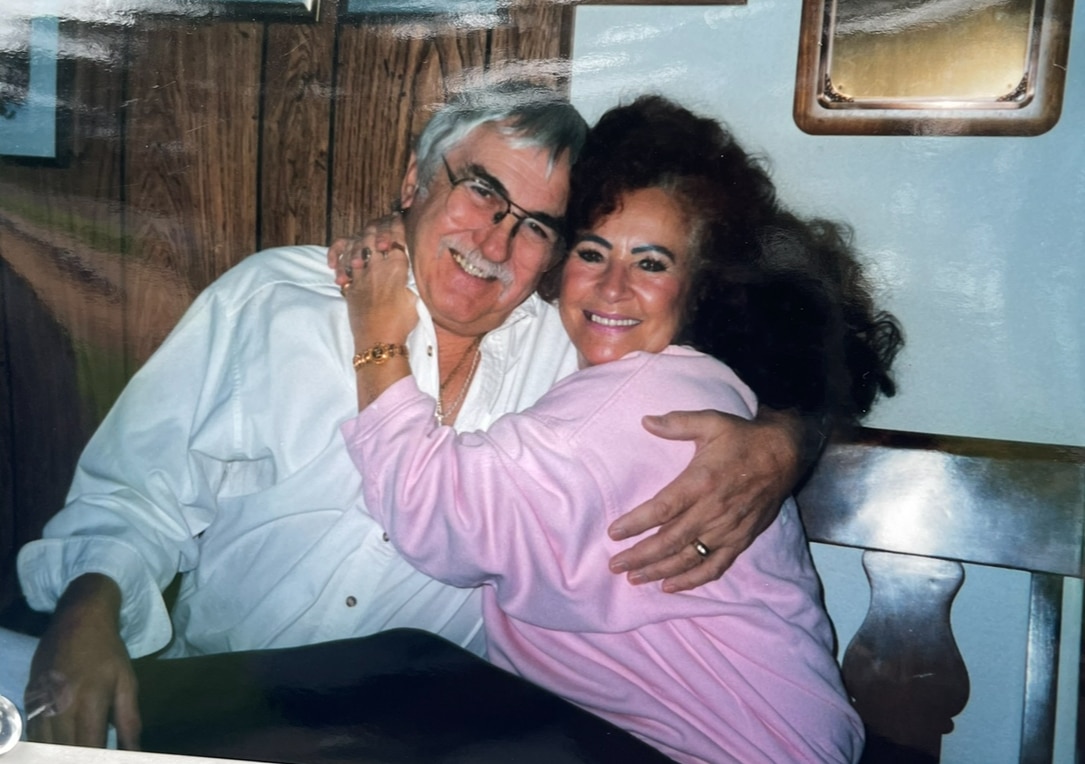

Delphine met Doug Farmer at Champion in Bonner, where he was a foreman. The way Bridges tells it, Doug was married, but after Delphine walked into the plant, he started telling people that’s the woman he was going to be with forever. His September 2014 obit includes this line: “He fell in love with the love of his life, Delphine, the moment he first met her.”

In Bridges’ Instagram post after her grandmother died, she wrote, “The love my Gramps had for her is unmatched. She has missed him for eight years now, so if heaven has Doug Farmer, pink pistols and fur, I have no doubt that’s exactly where she is.”

Bridges says Delphine (pronounced del-FINE) was, almost above all, fashionable—as she defined it. She wore cutoff shorts and had a deep tan. She tattooed on her eyebrows and dyed her hair red, even as she got into her 70s and 80s. “At my dad’s surprise 60th birthday party, her bright red hair was down to her butt. She had on this cute bomber puffer coat, parachute pants and Nike Air Force 1s,” says Bridges, who went through Delphine’s clothes before her dad sold the house. “It was all just this fun stuff I pictured her wearing. I got this ’80s T-shirt, hot pink, cut into about a thousand times. She wore it over a bikini. It looked great on her.”

Where things stand

Shane Field was the executor of both Doug’s and Delphine’s estates. He sold their house and then sold his own. Bridges says he helped his sisters move into a house in Missoula. It had been about 20 years since Shane moved into his own place up Donovan Creek, in a house behind his mom, her husband and Diane. He helped take care of them as they got older. His sister Debbie also lived with his mom and Diane after Doug died and she, too, looked out for Diane. Monty moved in with his mom and sisters at Shane’s encouragement after Bridges says Monty suffered a stroke. At the time of their mom’s murder, Monty was in a wheelchair, though Bridges says she understands that’s not permanent.

In a search warrant, detectives requested analysis of what looked like blood and a cleaning solution on Monty’s wheelchair. They also took the shirt Diane was wearing. She went to St. Patrick hospital the day her mom died with a cut on her forehead. Bridges had a photo of her on her phone. She showed it, but didn’t want it published. In it, her gray-haired aunt has blood dripping down her face. “She was hit with it, too,” Bridges contends about the fight with the antler, though how Diane was cut was not made clear in documents.

In the 911 call Monty made, he told dispatchers his sister hit his mom. He told the deputies who initially responded the same information and repeated it to detectives, according to warrants filed by the Missoula County Sheriff’s Office.

In a protective order Debbie Maplethorpe filed on behalf of herself and her sister, she wrote of Monty, “We had picked him up. My mom was murdered. He was one of the suspects and my sister. … He was very verbally abusive and relentlessly ranting. He is saying my sister did this. He claims he couldn’t get to them to stop them. But my sister tells a different story.”

That protective order was approved by a judge and, according to Bridges, Monty has not been in touch with his siblings. Phone numbers listed for Monty in Butte were inactive. There is an active and unrelated warrant out for him there—listed online by Butte-Silver Bow City Court.

Bridges says her dad still helps out his sisters and doesn’t like to talk about what happened, period. “That’s just not who he is,” she says. For this article, Bridges reached out to her dad and her aunt Debbie to see if she or Diane would talk about what happened. They declined. Debbie also didn’t answer a Facebook message.

In many ways, Bridges knows a trial involving her family would be difficult for everyone, herself included. But not having justice for her murdered grandmother? “To me, that’s worse.”