If you’re a certain kind of person this could feel like home. A double-wide trailer on the corner of Third and Catlin. A dark interior lit mostly by neon beer signs aided by the glow of a couple TVs, a perimeter of gambling machines, plus the festive aura of a Christmas tree that stays up year-round. The handle on the front door is wrapped in bright green duct tape that’s been worn smooth and soft and when you push your way inside there’s a certain gloaming darkness that wraps you up and carries you to the bar for some whiskey that comes out of a gun.

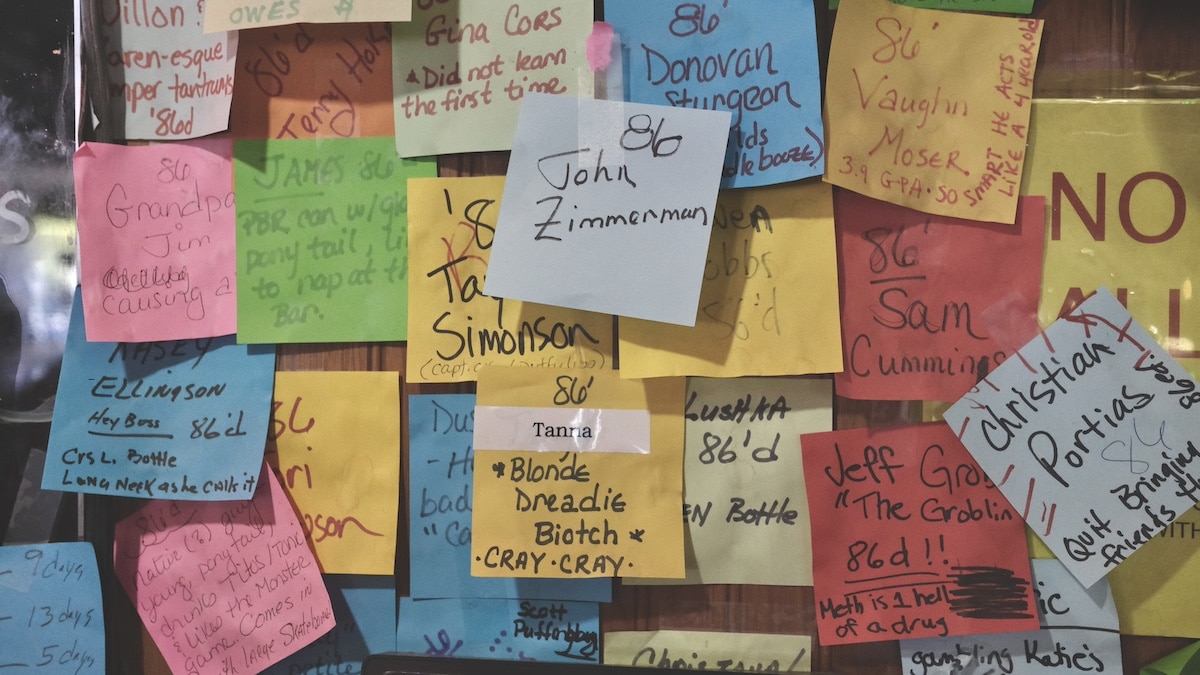

But then you’re sitting there, enjoying whatever dereliction of duty has brought you to this point, and your eye is drawn to the wall behind the bar. There you see dozens of Post-It notes and on these are written names or sometimes just descriptions and occasionally some combination of the two. And just when you’re starting to wonder if maybe they’re up there for having done something good you notice a few of these notes describe specific acts such as theft, harassment, or general assholery.

This is a wall of shame. It is a public record of misdeeds. On these Post-Its is a list of those who have sinned and been cast out of paradise. Woe unto them who have been added to the 86’d list at the Town & Country Lounge.

Woe unto them who have been added to the 86’d list at the Town & Country Lounge.

You can’t spend much time at the T&C (as it is known to regulars) and not notice the Post-Its. On this wall we learn that “Douchey Dylan” is no longer welcome, nor is “washed-up ’80s rocker chick” or “Steve the gambler” or “blondie dreadie bitch.” Here’s someone who is technically allowed in but forbidden from running a tab. Over there is a man who is “not a rapist just a drama queen,” which is the kind of description that only produces more questions. “Blonde Jacob,” whoever he is, apparently messed up enough to get an entire paper plate dedicated to his banishment, complete with colorful decorations and a place of honor high up all alone. Another paper plate with a first and last name started out as a mere Post-It, but, according to the T&C staff, it was upgraded when the unhappy recipient complained that it was libelous.

One name has been partially covered by the letters “RIP”—a reminder that you will leave this life but there’s no guarantee you’ll ever leave this wall. The bartenders here will tell you that the only way to get unbanned from the T&C is to plead your case directly to the bartender who banned you in the first place.

Bones, the great, gregarious panda of a man who works weekend shifts and never forgets a name, hasn’t had to 86 anyone in slightly over two years and yet still gets people begging to be taken off the list.

“I couldn’t imagine wanting so badly to be somewhere I knew I wasn’t wanted,” he says. “But I guess they feel like they just have to come to the T&C.”

Gisele, a silver-haired woman whose stoicism masks a wry and cutting wit, estimates she’s 86’d a dozen or so people over the years.

“Sundays are the worst for it,” she notes. “I don’t know what it is about Sundays.”

Lindsey Seelig is the bartender most recognizable to the weekend crowd. She’s got a distinctive staccato laugh that you can hear anywhere in the bar—ack, ack, ack, ack—like a mirthful machine gun. Like all great bartenders, she seems to actually care how you’re doing while also somehow appearing already sick of your bullshit when you walk in.

Lindsey’s tended bar at the T&C for around eight years, by her estimation. At this point she’s sort of like the conscience of the place as well as its memory. She can tell you a story to go with most of these names on the wall. She can tell you how it started as a list on a legal pad, then moved to this system that seems at once more haphazard and temporary yet at the same time more damning by its public nature. She can tell you how the ones on the poster board are from pre-pandemic times and had to be preserved after everything was removed from the walls for cleaning during those days of masks and go-cups and endless hand sanitizer.

The system does have a certain Library of Alexandria quality to it, so Lindsey sometimes wonders what would happen if a fire swept through and devoured all the little neon slips of paper.

“I guess it would just be a free-for-all,” she says. “We sometimes joke about putting all the names on like a scrolling LED screen behind the bar. But I don’t know, I think sometimes you need to see the handwriting and read the details.”

I’d probably only been to the T&C a handful of times during my first fifteen-ish years in Missoula. Then in 2021 I bought a house in the Franklin Park neighborhood—what my friend Dan, also a neighborhood resident, refers to as the “Town & Country Unified School District”—and it quickly became my favorite bar.

Through many happy hours with friends and nightcaps on the way home, I’ve seen all manner of misbehavior inside those frail walls. I once watched a man repeatedly headbutt the surface of a table in order to make a point to his friends about how down to party he was. I saw a woman spill most of a frozen margarita down the front of her shirt and then sit there insisting it was fine while doing nothing at all to aid everyone else’s efforts to clean it up. I’ve seen the same few people have to be reminded, again and again, that the sign forbidding dogs on the patio does in fact apply even to them.

I’ve seen aggressively lewd dances and loud arguments over the utility of winter tires and makeout sessions that made up for in intensity what they lacked in technical execution. And still I have never once seen someone get 86’d. Staring at the still growing armada of Post-Its on the wall, I couldn’t help but wonder what it would possibly take.

Turns out it’s probably not what you’d think. Alcohol-fueled violence is relatively rare, according to Lindsey.

“I’ve only had to break up a handful of fights,” she says. “It’s just not the kind of place where we really have to worry about that.”

The bartenders agree that the No. 1 cause of banishment is repeated drunk driving. People get told. They get warned. They keep doing it anyway, perhaps overestimating their ability to mask their inebriation while skulking out to their cars. Eventually they get banned.

“Sometimes we’ll give people a 30-day suspension and kind of say, ‘Hey, if getting hammered and driving the four blocks to your house is that important to you, you won’t be with us,’” Lindsey says. “But the thing is, when we give somebody 30 days and then those 30 days are up? I’d say 90 percent of the time they end up on the fucking wall.”

The other things that get people banned most often are theft and abusive behavior toward the staff. One patron, apparently intent on combining the two, ended an argument with a bartender by reaching around the bar and swiping his cigarettes—seemingly not because she wanted them, but rather in some vague act of defiance. Sure enough, she’s on the wall. And like many people who end up there, she later returned to plead her case.

This is the other thing the bartenders here will tell you. People who get excommunicated from the church of the T&C do not tend to meekly accept their punishment and slink away in shame. Some try to sneak back in, sometimes even employing some manner of disguise. Others simply beg. A few have opted to argue or threaten, behaviors that only confirm the rectitude of the judgment.

“Some people just continuously try to come back and hide outside on the patio or at a different table,” Lindsey says. “It’s like, this is the seventh time I’ve had to tell you since we 86’d you. And just, why? It’s not like there aren’t other bars in this town.”

Which, of course, is true. Missoula is a smorgasbord of bars. The proportion of classic dive bars may be dwindling—gone is the Silver Tip, the Elbow Room, Buck’s Club, and a half-dozen others we could sit around naming like old baseball players from the ’90s—but it’s not as if one ever struggles to find an empty barstool in this town. Even if Missoula’s bar scene sometimes feels like it’s gentrifying as quickly as the condos go up, let us be honest enough with ourselves to admit that many of our beloved downtown mainstays would qualify as lovably dingy dive bars in many other cities.

Point is, it shouldn’t be such a big deal to get cast out of the T&C with so many options that are, at least on paper, pretty comparable. And yet as a T&C regular I somehow immediately understand why those who’ve found themselves on the business end of those Post-It notes sometimes carry it like they’ve been disowned by their families.

My dear friend Amy once thought she might get banned for, in a moment of boisterous enthusiasm, attempting to mountaineer her way to the top of a Keno machine. Turns out, no, that’s nowhere near a grave enough sin to warrant exile (at least with no history of prior bad acts). But the possibility alone put a scare in her.

“Can you imagine not being able to go to the T&C?” she says, with a look of genuine horror. “I think I’d cry.”

So what is it? Of all the places to get a shot and a beer in this town, what’s so special about this trailer in the Good Food Store parking lot? Why do dirtbags like me and Amy and Douchey Dylan and the washed-up rocker chick all seem to feel like we simply must gather there?

On this I have heard a few theories. One is that it’s a neighborhood bar perfectly positioned for an over-30 crowd that isn’t up for going downtown unless there’s a truly special event requiring it.

“Plus it’s a cheap place to drink that’s pretty no-nonsense,” Lindsey says. “And it’s right there in the middle of town.”

Amy insists it’s the staff—a lineup of cocktail-slinging professionals who are as genuine and unpretentious as the place itself.

“The people are what make it,” she says. “Without them, I think it’d be an entirely different experience.”

This was echoed by my friend Kasey who noted that when her truck broke down while driving past the T&C she was “almost delighted.” A small platoon of strangers rose up from the patio to help her push it into an empty parking spot and the reaction from bartenders suggested she was not the first person to ever ask if she could leave a disabled vehicle in their lot for a short time.

A neighbor of mine once likened the T&C to Superman’s Fortress of Solitude in the sense that it’s a place you can go to be somewhere other than home while also not having to worry about socializing. It’s a place you can just go to, he explained. Maybe your friends will be there and maybe they won’t, he said, but either way you don’t need to make (and here his voice dripped with disdain) plans.

There’s something to all these theories. I also think there’s a certain endangered species quality to the place in today’s Missoula. Here’s a bar that is utterly unpretentious, with its half-broken stools and its vodka bottles hanging upside-down for quick and easy access. Nobody’s trying to overcharge for craft cocktails while pretending they’re in Seattle or Brooklyn. The slow creep of chain stores and real estate vampirism has not yet found this place, which makes it feel like a refuge and a relic.

To be banished from a place like that feels like more of a failure of character than of etiquette. You get your name stuck to that wall and it lets everyone else know: These are the people who would fuck up a good thing. And then where will you be? And who will love you there?